Will a new 60-day cap on shelter stays put more migrants on the street? NYC officials say it might.

Aug. 10, 2023, 8:04 p.m.

The question was on the minds of City Council members, who grilled Adams administration officials on the new shelter rule for asylum-seekers.

Where will asylum-seekers in New York City go when they hit Mayor Eric Adams’ new 60-day limit on shelter stays?

That was the burning question, repeated in a flurry of exchanges, during a Thursday afternoon City Council oversight hearing on Adams’ new policy, which aims to turn over space more quickly for migrants. It applies only to single adults.

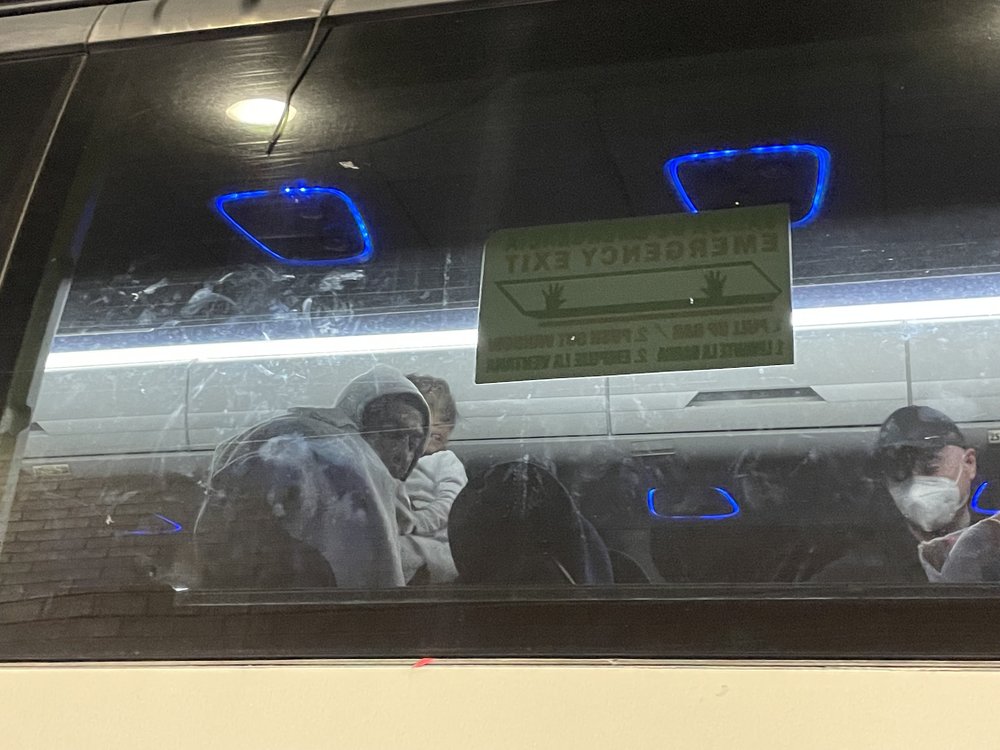

Administration officials told councilmembers those at the end of their 60-day limit could re-apply for space, but wouldn’t guarantee beds would be available. They also wouldn’t foreclose against the recurrence of recent scenes in Midtown, where last week hundreds of migrants slept on the sidewalk outside of the Roosevelt Hotel, the city’s central intake center for migrants, before being moved.

“Let me be clear: We do not want anyone sleeping on our street,” said emergency management Commissioner Zach Iscol. He later added, “We are still fighting every day to keep that from happening.”

Let me be clear: We do not want anyone sleeping on our street.

Zach Iscol, NYC emergency management commissioner

Pressed by councilmembers who said they were concerned the new policy would put more people on the street, Iscol said the administration faces hard choices.

“We have to make decisions every day that are impossible choices that we don't want to have to make…Would you rather have somebody on the streets who has been here for two hours?” Iscol asked. “Would you rather give somebody 60 days, help them get on their feet and open up a bed for that person?”

Notices have gone out

The 60-day limit was intended to free up shelter space for families with children and new arrivals—and avoid more migrants sleeping on the streets. Officials said they’re working tirelessly to open emergency sites at the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center campus in Queens next week, and Randall’s Island soccer fields the following week.

Over 1,400 notices have gone out in the last two weeks, most going to those migrants who have been in the shelters the longest. Many recipients, officials said, have said they weren’t aware that help was available for them to travel elsewhere, assistance referenced in the notices.

Ted Long, senior vice president of the city’s hospital system, said 65% of people who have received notices thus far are “ready to make an exit plan.” They just need assistance, he said, such as a bus ticket to another city, English classes, construction safety certifications, or a New York City ID (IDNYC), based on discussions with case managers.

“Nobody's surprised when we're giving them the 60-day notices,” Long said.

City Council members and other officials acknowledged the challenge of housing so many newcomers–currently more than 57,300–but several voiced displeasure over the city’s policy, and responses.

“While the administration claims the goal is not to force people into the street, we already see it happening,” Public Advocate Jumaane Williams said, pointing to lengthy overnight lines outside the arrival center, and a migrant camp erected under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

“I don't want to throw migrants into an unfamiliar pool of water and hope that they can swim,” said Deputy Speaker Diana Ayala. “I want to know that they can swim.”

When pressed by Ayala, Iscol said if the city saw a “marked increase” in street homelessness because of the policy, “We would adjust.”

Williams said he worried the policy would erode a decades-old court mandate requiring the city to provide shelter for homeless people who meet certain minimum conditions. The Adams administration requested in court this spring that a federal judge limit the city’s obligations under the so-called right-to-shelter.

“There have been people who wanted to chip away at the right to shelter for a very, very long time,” Williams said. “My biggest concern is that chipping it away now will weaken it and allow it to go away forever.”

A lack of state and federal support, Immigration Committee Chair Shahana Hanif said, doesn't justify the "deterioration of the right-to-shelter mandate. Or our status as a sanctuary city and our welcoming spirit.”

Hanif chided the administration’s lack of transparency in decision-making around migrant shelters in the city.

“I understand the necessity to be flexible,” she said. “But the general opaqueness of policies being announced, versus whether policies are being implemented without public disclosure or disclosure to the council has been a concern of mine.”

Long said that 300 to 500 people go to the asylum-seeker arrival center outside the Roosevelt Hotel in Midtown every day. Within 24 hours, 1 in 4 then go elsewhere, either to another city or local housing outside of the city’s shelter system, he added.

Since spring 2022, some 100,000 people have gone through the city’s intake system. And 40%, or nearly 40,000 people, have left the city’s care, Long said.

For migrants in NY, stays in some city shelters have hit rock bottom, advocates say A ‘30 Rock’ veteran and comedian takes on New York’s migrant crisis Eased tensions between Mayor Adams and Biden administration on migrants — for now