Widow kicked out of home, African art collection in jeopardy, as city orders demo of Bed-Stuy building

Nov. 17, 2022, 9:40 a.m.

The building owner won a temporary reprieve after Gothamist began making inquiries.

A widow was ordered to vacate her home of more than a decade and the fate of her late husband’s African art collection hangs in the balance, as the New York City Department of Buildings pursues an order to demolish her home due to a crack in the building’s rear wall.

Barbara Wentt-Simmons, a 69-year-old public school dance teacher, is trying to stave off her home’s destruction and that of the Simmons Collection African Arts Museum, a shuttered community museum run by her late husband Stanfield Simmons Jr. until his death in 2010.

Barbara Wentt-Simmons at the shuttered Simmons Collection African Arts Museum, a community museum she helped her late husband run until his death in 2010.

At the time of Simmons Jr.'s death, Mayor Eric Adams, then a state senator, commended his efforts. But after a complaint from a developer who owns the building next door, Adams’ buildings department signed off on a demolition order on Sept. 9, records show.

Last week, a judge denied Wentt-Simmons' plea for a restraining order that would have delayed demolition while she pursues a lawsuit against the city.

"They said [this week] the building should be down and I'm saying ‘Over my dead body,'" she said.

Workers with the buildings department have already gone into the building and covered the artwork on the ground floor with tarps as they prepare to remove it ahead of the demolition.

Wentt-Simmons is still holding out hope that they’ll reconsider and allow her to make repairs to the building so it can safely remain standing.

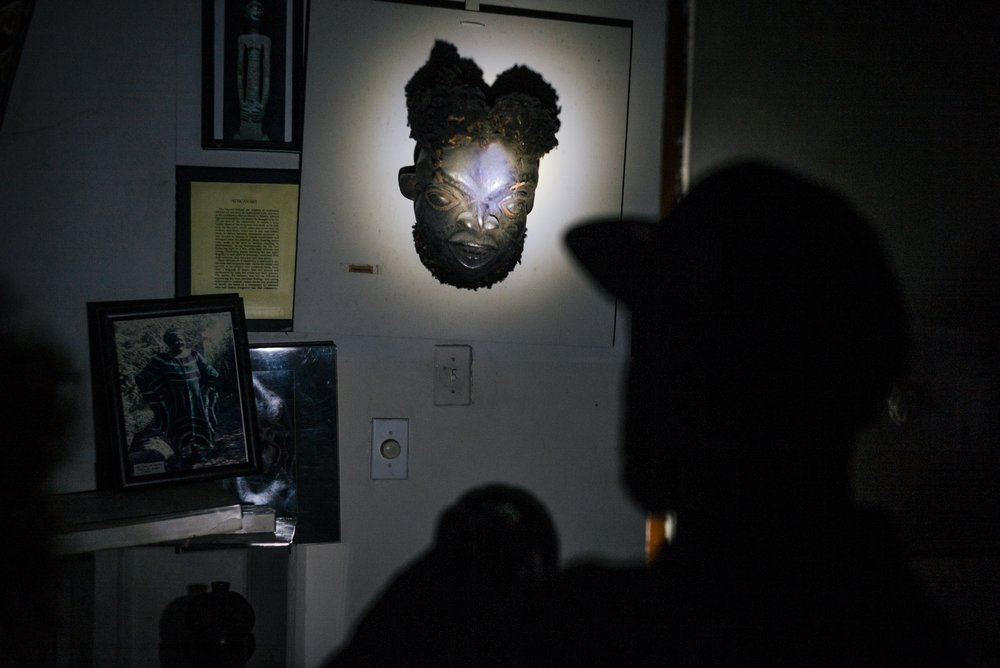

The collection now hangs behind plastic tarps, in preparation for the building's demolition.

“I know that building is not gonna be torn down,” said Wentt-Simmons. “My husband's energy, spirit, his hard work is in there. The love from what he started and built for this community.”

Wentt-Simmons was offered a glimmer of hope this week, after an inquiry from Gothamist to the buildings department. Joseph Esposito, the department's deputy enforcement commissioner, reached out to Gary Purdy, who is helping manage the estate of Wentt-Simmons’ late husband. Esposito told Purdy the department would return to the building with structural engineers from both parties and re-examine it before the end of the week.

“This is giving me a good feeling about where things are going,” Purdy said. “That’s the situation.”

Barbara Wentt-Simmons, center, and friends who are advising her. From left: civic and structural engineer, Gommaire Michel; civic and structural engineer, Anthony Reneaud; and Gary Purdy, who Mrs. Wentt-Simmons said is like a son to her.

Jonah Allon, a spokesperson for the mayor, said the building’s back wall had partially collapsed and buildings department officials tried to get Wentt-Simmons and her associates to provide a plan to repair it. He said officials only moved forward with the planned demolition when they weren’t provided a plan.

“We have proactively engaged with the owner, and have put together a plan to work with them to safely remove and protect the artwork prior to demolition,” Allon said.

The three-story townhouse is located in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood — an area that has seen dramatic gentrification over the past decade, making the property a prime piece of real estate.

No one doubts the crack in the building’s back wall is dangerous and needs to be addressed immediately, said architect Glen Campbell, one of several experts who signed affidavits in support of Simmons’ estate in the lawsuit. What he doesn’t understand is why the city is insisting the building must come down, rather than letting them make urgently needed repairs.

“I don't have a problem putting my reputation on the line with regard to this case,” Campbell said. “If they give us the opportunity tomorrow to repair this, we would go in there, bring in the contractor, and get this thing done in short order.”

Part of the collection at the shuttered Simmons Collection African Arts Museum.

Wentt-Simmons’ late husband Stanfield Simmons Jr. first purchased the two-story building at 1063 Fulton Street in 1986, using the commercial space on the ground floor to display his carefully curated collection of African art that he’d amassed over a lifetime of international travel. Simmons Jr. was a Wall Street paralegal turned art aficionado who traveled the world, bringing some artifacts back to share with his neighborhood. His extensive collection includes masks, figurines, ceremonial objects and statues from countries across the African continent, as well as from Papua New Guinea, Brazil, and the African diaspora.

“He was very proud of our African heritage and he wanted to share that with the community. And not only the community, but people from all walks of life,” Wentt-Simmons said.

When Simmons died, then-State Sen. Eric Adams introduced a resolution to the Legislature to honor his death describing the cultural tours Simmons led abroad as well as the generations he mentored at his museum and in schools across the city.

“Armed with a humanistic spirit, imbued with a sense of compassion, and comforted by a loving family, Stanfield Simmons Jr. leaves behind a legacy which will long endure the passage of time and will remain as a comforting memory to all he served and befriended,” Adams wrote in 2010.

After Simmons Jr.'s death, Wentt-Simmons moved into the apartment above the museum, but struggled to keep it open with a full-time job of her own. She had aspirations to renovate it and reopen it to the public. Though it seems that dream is on hold.

While Wentt-Simmons was vacationing in Brazil in August, developer Reuben Pinner of the RYL Group, which owns the vacant building next door, called the buildings department to warn them of the crack in the back wall of her building, he confirmed.

The shuttered Simmons Collection African Arts Museum in Bed-Stuy.

They’d been anxious to move ahead with their plans to demolish their vacant property next to Wentt-Simmons’ in order to rebuild a six-story, eight-unit condo building, he said. But when they saw the massive crack in the back of Wentt-Simmons’ building, they feared their work could cause part of her building to crumble. Inspectors visited the site the next day and ordered the building to be vacated, records show.

When Wentt-Simmons returned from her trip, she packed up a small bag of belongings and left the rest of her life behind. She’s been renting out an apartment from a friend of a friend since then, anxious but unable to return home.

After she’d moved out, she got a call from the mayor, who told her he’d heard about the demolition and was wondering what she was going to do with her late husband’s artwork. Former Councilmember Laurie Cumbo later reached out to see if she wanted a place to store it.

“Like I said, nobody's touching anything,” Wentt-Simmons told them.

This story has been updated with comment form City Hall.

Reece T. Williams contributed reporting.