Why these NJ schools are so diverse, while many are segregated — affordable housing has been key

July 17, 2023, 6:01 a.m.

The Mount Laurel Doctrine, New Jersey's groundbreaking affordable housing rule, has been on the books for nearly half a century — but few towns lived up to its intent. Franklin Township bucked the trend.

First-graders at Franklin Park School in Franklin Township, New Jersey have breakfast and complete the morning activity. The school is part one of the most diverse school districts in the state.

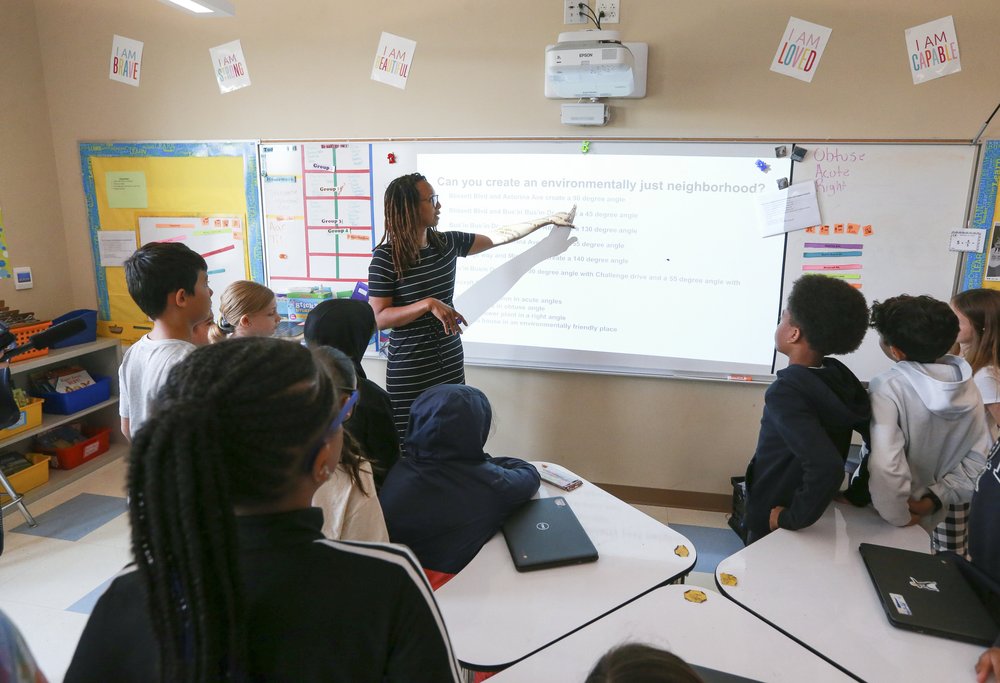

The fourth-graders at Claremont Elementary School in Franklin Township, New Jersey already know many of the basic building blocks of a good neighborhood. Days before the end of the school year in June, they were busy designing environmentally friendly communities using protractors and poster-sized dry erase boards.

One agreed-upon guideline among the 9- and 10-year-olds: Houses belong near leafy parks, not by gas stations or power plants.

"[People] can get really sick because of all the pollution that's like right by your house,” student Jaynellie Rodriguez said.

Like her imagined neighborhood, Rodriguez said her real house is by a big wooded area. But she knows that’s not the case for each of her classmates, who come from all sorts of socio-economic and racial backgrounds.

It's a discussion that feels natural in Franklin Township Public Schools in Somerset County, one of the most diverse districts in New Jersey, according to a report card issued by the state education department. Housing advocates say the township is a model for the rest of the state because of its embrace of a set of nearly half-century old court rulings mandating affordable housing.

The unusual legal mandate known as the Mount Laurel Doctrine was the first of its kind in the country to incentivize low-cost housing production through municipal zoning rules. But the doctrine, which is still in effect, has a tattered history of enforcement. For two decades, lawmakers allowed wealthy towns to pay their way out of their court-mandated housing obligations, and students in those municipalities generally attended much less diverse schools, Gothamist found.

Now the state is fighting a lawsuit filed by a coalition of nonprofits alleging it sends tens of thousands of Black and Latino students to segregated schools that are just 1% white. The nonprofits say assigning children to schools based on where they live — in a state with 564 municipalities and nearly 600 school districts — replicates existing residential segregation inside classrooms. The lawsuit cites a study that found New Jersey schools are among the most segregated for Black and Latino students in the U.S.

One solution, housing advocates have long argued, is to make the state’s housing policy better reflect the economic and racial diversity of New Jersey’s population. In that regard, they said, Franklin Township is a leader. The 7,000 students at Franklin Schools speak more than 65 languages and are about 37% Hispanic, 33% Black, 15% Asian and 11% white, enrollment data shows. About 40% receive free or reduced lunch, an indicator of the proportion of low-income families. In town, about 25% of the township’s housing stock is multi-family homes.

“Housing is the most powerful driver of segregation, especially when we have a state that assigns schools based on municipal lines,” said Adam Gordon, executive director of the Fair Share Housing Center, a nonprofit created to defend the doctrine.

The nearly 50-year-old pair of Mount Laurel rulings were supposed to create more housing choices for low-income families, yet weak enforcement and political promises to end the mandate have let many municipalities sidestep the rulings’ intent. Many towns ignored the ruling for the first decade. In 1985, lawmakers allowed towns to shift their affordable housing obligations to other communities, paying other towns to provide the housing instead. This loophole, using arrangements known as regional contribution agreements, was banned by the state Legislature in 2008.

A Gothamist analysis found 90% of towns that used the agreements to offload their affordable housing obligations to communities outside their borders currently send their students to schools that are whiter than the state average. Four-fifths of the towns that used the loophole sent their kids to schools that had more white students than nonwhite. Gothamist also found that almost all the towns that used the agreements have fewer students receiving free or reduced lunch than the state average.

Though state lawmakers eventually ended the loophole, the Mount Laurel doctrine remained a political target. During Chris Christie’s time as governor, he tried to dismantle the state agency responsible for overseeing affordable housing obligations entirely. It wasn’t until the state Supreme Court tasked the lower courts with enforcing the doctrine in 2015 that housing advocates said Mount Laurel finally began to be implemented as intended across the state. But the scattershot enforcement of the doctrine has limited its reach in shaping municipalities and their schools.

“Our goal was to try to get the children, particularly, into having access to a safe environment and better schools,” said Peter O’Connor, one of the original lawyers on the Mount Laurel case. “Everyone involved in the cases and in the legislative efforts knows that that was the ultimate goal, integration.”

The opportunity to build

New Jersey’s groundbreaking affordable housing rulings began in the town that gives the doctrine its name — a community about 15 miles from Camden called Mount Laurel. In the mid-1900s, Black families resided in small frame homes poorly maintained by landlords or in converted chicken coops because they couldn’t afford single-family homes on a half or one-acre lots.

Gordon said rural Black communities in New Jersey grew around churches that were stops on the Underground Railroad, final destinations just over the Mason-Dixon line.

“We were the first stop north for freedom for a lot of people who were enslaved. And there were these very strong communities,” Gordon said. “As suburbanization, white flight started to happen in the ’50s and ’60s, a lot of those communities became targeted for development.”

When Mount Laurel officials began demolishing those poorly maintained homes and rejected plans to allow the Black community to build multi-family houses, Ethel Lawrence, a daycare worker and organizer, challenged those decisions in Superior Court in 1971. She won in a case that would make it all the way to the state’s highest bench and define New Jersey’s housing policy for decades to come.

In a pair of decisions in 1975 and 1983, the state Supreme Court ruled municipalities had to make realistic opportunities for low- and moderate-income housing.

“We didn’t ask Mount Laurel to build affordable housing. We only asked them to relax the zoning laws they’re planning, to allow us the opportunity to build,” Lawrence, who died in 1994, told the New Jersey Network in 1985.

O’Connor, one of three attorneys on the case, said towns used zoning laws and draconian rules to “basically keep the suburbs white and to keep them middle- and upper-income, and to have a white, homogeneous school population.”

Lawmakers in 1985 passed the Fair Housing Act, creating a state agency called the Council on Affordable Housing, or COAH, to enforce the doctrine. It was charged with assigning each municipality the “fair share” number of affordable housing units it needed to provide. Those obligations could be met by rehabilitating existing substandard lower-income housing, approving multifamily construction or changing zoning laws to allow denser development.

But lawmakers also created regional contribution agreements, which let towns transfer as much as half their obligations — along with funding — to cities.

“For the first 20-plus years of real enforcement of Mount Laurel, the wealthiest towns could pay out of having families in their towns. And that really undermined this process,” Gordon said. “The wealthiest towns had the money to buy out, and the more middle class suburbs didn't, and often the more middle-class suburbs were meeting their obligations and the super wealthy towns weren’t.”

‘This is what the world is like’

Franklin Township, nestled in one of the richest counties in the state, is a 46-square-mile municipality bookended by Rutgers University and Princeton University. As Mayor Phillip Kramer describes it, its borders are shaped like a miniature South America, with the densest housing in the northeast near New Brunswick.

Franklin has diversity “in every way you can think of,” Kramer said. “Geographically, we have urban, we have farms. We have very rich people, and we have people who need affordable housing. We have racial diversity and religious diversity. One time we counted — there's 70 houses of worship in town.”

Kramer and other township officials say Franklin has long been diverse, but became increasing so in the last decade, at a faster rate than statewide trends. But while Franklin schools have remained relatively diverse, new pockets of segregation have emerged in districts across New Jersey, according to an NJ Spotlight analysis of Census and statewide enrollment data.

It found New Jersey’s population, currently 9.3 million, added 1.4 million people of color in the last two decades, primarily Hispanic and Asian, while the number of white residents fell by 740,000. That diversity has spread to every county, resulting in fewer school districts that are predominantly Black or predominantly white, the analysis showed.

But the state also added new clusters of segregation: the number of districts where 80% or more of students are Hispanic more than tripled in the last 20 years. Additionally, about four in 10 schools in New Jersey had some level of segregation, defined as being made up of at least 80% of one race or ethnicity or a combination of nonwhite groups, Spotlight found.

“Those communities that are segregated, whether it's all-white communities or all-Black communities, they're losing something by not having access to, and the ability to interact with people from different backgrounds,” said Taiisa Kelly, CEO at Monarch Housing Associates, a nonprofit that helps develop affordable housing in the state.

Kelly is also a 17-year resident of Franklin and a parent of four public school children.

“If you have a town that purposely doesn't build anything for other economic classes or races, then you create this enclave of a white town, a white school district,” she said.

That’s not the case in Franklin. The township has OK’d nearly 2,000 affordable housing units since the doctrine came into effect, and most are already occupied, according to its Mount Laurel plan. Gordon, of Fair Share Housing, said Franklin stands out because it was consistently rezoning its land and making room for affordable housing development.

It is, however, one the 121 municipalities that offloaded some of their affordable housing obligations to other towns through regional contribution agreements. But Franklin only transferred a small portion of its obligation — 29 units — to nearby Perth Amboy, according to data provided by Fair Share Housing. It largely met the rest of its obligations within its borders, township officials said.

Fair Share Housing provided Gothamist with a dataset of towns that used regional contribution agreements. Gothamist analyzed that data and compared it with the towns’ school enrollment numbers.

That analysis shows that of the towns that offloaded their obligations through the agreements, Franklin’s school district has the highest proportion of non-white students, at 89%.

“What a great experience you get when you attend a school like this. I mean, this is what the world is like,” Franklin Schools Superintendent John Ravally said. “This is what the community is like. But so many kids don't have this experience in school.”

Jaiden Gourdine, a rising junior at Franklin High School, said he notices the school’s diversity when he plays sports against other teams.

“When we have track meets, I can really see how diverse our school is compared to the other schools,” Gourdine, 15, said. “We have people of different races and ethnicities, whereas other schools don't really have that.”

Gordon said the effects of towns dodging their housing obligations — or embracing them like Franklin — has rippled through the state’s school system.

“The schools are just much more economically and racially integrated than would've ever happened without Mount Laurel. And then there are other places that have resisted it for years and very little has happened,” Gordon said.

‘We just kept going’

When Christie became governor in 2010, he followed through on a campaign promise to gut the state agency enforcing the Mount Laurel doctrine. He repeatedly tried to abolish COAH, the state agency in charge of enforcement, but was blocked by the state Supreme Court. COAH also failed to issue new housing obligations for towns and then Christie stopped convening agency meetings, effectively halting the agency’s work approving towns’ affordable housing plans.

Even as enforcement stopped, affordable housing construction in Franklin continued. Township officials approved projects and rezoned land to accommodate higher densities.

“We knew the obligation was going to come back,” Mayor Kramer said, adding that Franklin officials saw affordable housing as a benefit to their community. “We just kept going.”

In 1970, a few years before the first Mount Laurel ruling, there was no land zoned for multifamily housing in Somerset County, where Franklin sits, according to state court records. Multifamily housing is generally more affordable for residents who can’t afford single-family homes.

Now, a quarter of Franklin’s housing stock is made up of multifamily units, a quarter are townhouses and less than half are single-family detached homes, township planner Mark Healey said.

“Franklin has been one of the best towns in the state in terms of how it's met its obligation,” Gordon said. “I think it's had a really consistent track record of building a range of different ways of doing affordable housing and doing it in a way that is good planning and that has had a real impact for a lot of families' lives.”

But school integration in the township has had some limitations. While Franklin’s population is 28% white, just 11% of its students are — a measure that some studies consider a segregated district. Teachers, students and parents say many white families enroll their students in private or local charter schools, especially after elementary school.

“In an ideal world, there would be space for parents to be more exposed as well to [conversations about integration],” Kelly said. “And that they're embracing that opportunity for integration.”

She said Franklin’s embrace of Mount Laurel shows “it's possible to create integrated schools that do well. It shows us that education is more than just academics. It's also about the social environment that you create for students.”

Claremont Elementary teacher Ebony Blissett said she recognizes that the diversity in her fourth-grade class isn’t something teachers or school leaders have much control over. But in response to its diversifying student body, the district has implemented an anti-racism policy and is training teachers to be more culturally and linguistically responsive to their students. They even hired a supervisor of equity and inclusion.

“Franklin tries to bring students from different economic situations together in one school so they can learn from one another,” Blissett said. “But teachers have an important role as well in doing their best in allowing students to see outside of themselves and see other people.”

During her math and social students lesson on building neighborhoods, Blissett wanted her class to think critically about why they live in different environments. She had the students look up their own houses on Google Earth to see what was around them, and they noticed some differences.

Ten-year-old Sam Zippilli reflected on what she saw. “If there is environmental justice, which there isn't right now, it means that everybody is equal in terms of their environment, how healthy their environment is, not depending on how much income you have,” she said.

- heading

- Segregated NJ

- image

- image

- Segregated NJ.jpg

- caption

- body

In study after study, New Jersey — despite its diverse overall population — has been found to have one of the most segregated public school systems in the country. More than a dozen newsrooms covering New Jersey have come together to explain how it came to this, what might be done about it and how segregation affects the student experience.

The series, Segregated, includes reporting from Gothamist and WNYC, NJ Spotlight News, Chalkbeat Newark and newsrooms serving several communities. The continuing reporting can be found at SegregatedNJ.org.