Where are they now? Migrants who slept on the Midtown sidewalk.

Aug. 28, 2023, 5:01 a.m.

Although many found the scene of outstretched bodies on the pavement unsettling, the widely circulated images appeared to spur government action.

An asylum-seeker from Senegal said he felt deeply embarrassed after a friend back home sent him a screenshot from a French TV broadcast about the migrants sleeping on the sidewalk in New York City. “If I had known I would've been sleeping outside, I wouldn't even come,” said C.S., who asked his full name not be used because of fear it would harm his immigration case.

Another migrant, Savi Khalil, spent three days and nights on the same pavement in Midtown just weeks ago. He said a TikTok video of his ordeal found its way to his mother back home in Mauritania. He wondered how such a “powerful country” like the U.S. could have people sleeping on the street.

They were among the hundreds of new arrivals who recently slept overnight in the scorching summer heat — some for days on end — on the sidewalk outside the city’s asylum-seeker arrival center, the Roosevelt Hotel on 45th Street, amid what would become a national and international media storm.

And the newspapers were coming, recording us, showing us to the world without trying to help.

C.S., an asylum-seeker from Senegal

Photos and videos of the mostly Black men, who were splayed out on flattened cardboard boxes and using their backpacks as pillows while office workers, tourists and others hurried past, circulated on TV screens and in TikTok videos. The city’s yearlong influx of newcomers had remained largely invisible to most New Yorkers, perhaps even to the world, until the outstretched bodies were seen lining the sidewalk.

Onlookers gawked and described the scene as “chaos” and “a disgrace.” Several, and even some of the migrants themselves, wondered why, in the wealthiest city in the world, were hundreds of people sleeping on the street? Had New York, which had accommodated more than 100,000 asylum-seekers since spring 2022, abandoned even the pretense of being welcoming?

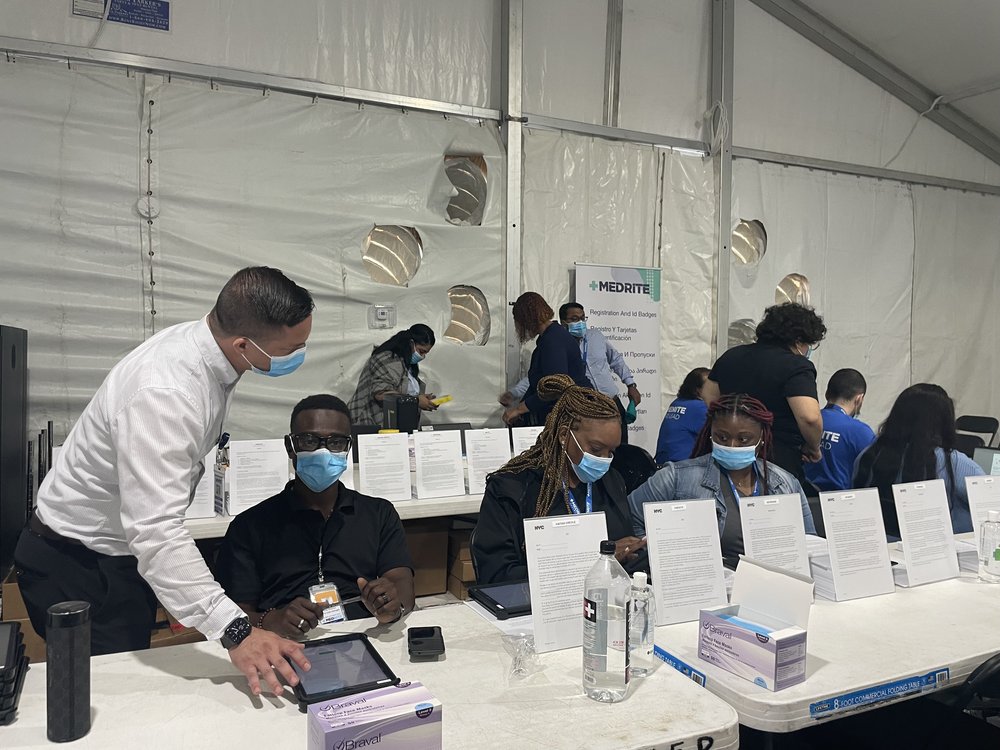

But the attention touched a chord. City Hall, which professed to be out of shelter space for new migrants, quickly found more space and bused those camped out in Midtown to an old church building in Queens. And, in short order, the Biden administration sent emissaries to New York, while both the Adams administration and Gov. Kathy Hochul unveiled plans to add thousands of new beds for migrants, including on the sprawling Floyd Bennett Field in southeast Brooklyn.

Weeks later, many of the migrants who spent those sweltering days on the sidewalk now sleep on cots in a new tent city erected in a parking lot of a state hospital in Queens. Those with working phones send WhatsApp voice memos to loved ones back home, post celebratory photos taken on the subway and in Times Square, and make little mention of their hardships.

In interviews, however, some of those migrants told Gothamist their days at the center of a media spectacle form painful memories filled with indignation, anger and regret — among the first of many unfulfilled promises of life in the U.S.

Most spoke little to no English, and a few spoke through an interpreter. Nearly all the men interviewed asked that we not use their last names and instead identify them with a middle name, nickname or their initials, for fear of jeopardizing their immigration cases — and to avoid further embarrassment.

Here are some of their stories.

C.S., 30, Senegal

Even in low-resolution, C.S. recognized the screenshot of the man’s profile as his own.

A friend back in Senegal sent him the still photo over WhatsApp. It had been taken from a TikTok video that aired on French public television. The TikTok caption read, in French: “Mauritian migrants who spent the night outside in New York.”

The still showed C.S. in line at the Roosevelt Hotel, hunched over a metal barricade separating new migrants seeking shelter from passersby. He winced and shook his head as he looked at the image on his phone while sitting on a park bench across the street from his new home, the tent shelter at the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center.

The U.S. was never his ultimate dream. But when C.S. would tell his family and loved ones back home that he was journeying here, he thought he’d be in a better situation — or at least somewhere inside. He’d never slept outside before, let alone for four days, until now.

“And the newspapers were coming, recording us, showing us to the world without trying to help,” he said. He had tried to hide his face from the cameras.

He later added: “If I had known I would've been sleeping outside, I wouldn't even come.”

Loved ones transferred him money while he traveled to the U.S. over the summer, but now he feels indebted since he can’t repay them. He wants to send money back home to his wife and two children as well.

Day after day, C.S. canvasses nearby businesses, such as restaurants and car washes. But he still can't find work.

“I don’t know anything about my future right now,” he said. “I just have hope.”

Savi Khalil, 31, Mauritania

When Savi Khalil decided to leave his home, the West African country of Mauritania, he knew the journey ahead would be difficult — that maybe he’d even end up sleeping on the street.

“You can say, I was ready for it,” he said on a recent day. He had just returned from a mosque with a group of other Mauritanian men, who were all sitting on playground benches across the street from the Creedmoor shelter.

Other Mauritanian migrants told Gothamist they fled their homeland due to anti-Black racism and inequality. Khalil said he’s part of the Haratine ethnic group, who are sometimes referred to as “Black Moors” and are distinct from the lighter-skinned Berber people who more commonly occupy positions of power in Mauritania.

Khalil said policemen beat him and his friends as they protested high food prices two years ago. Thousands of protests broke out across the African continent at the time due to rising consumer prices, which were partly driven by wheat shortages from the Russia-Ukraine war.

“Since that day, I hate my country,” he said. “I decided to do anything to move out from that country to go anywhere… Just to get out from that hell.”

Khalil’s journey included 12 hours traveling by boat from a city just north of the Guatemalan border, then to another Mexican town further north up the coast. He spent three days in jail in Mexico City because he didn’t have a visa. Against that backdrop, had this to say of his days spent sleeping outside the Roosevelt Hotel: “It’s nothing.”

Nonetheless, when Khalil’s mother in Mauritania asked about an interview he gave with the New York Times — which appeared on TikTok — after sleeping outside for three days, he told her he wanted to send a message to the mayor of New York City.

“I was asking a question. USA is the most powerful country around the world,” Khalil recounts telling her. “How in the most powerful country around the world, they have immigrants sleeping on the street?”

Moris, 31, Senegal

Moris spoke to family members on WhatsApp on each of the six days he spent living outside the Roosevelt Hotel. But he waited to tell them where he had been living until he found another place to stay. If you tell people your problems, he thought, they’ll always see you as needy, and he didn’t want to be seen that way.

He recalled seeing himself in TikTok videos, where he is seen waiting in line outside the hotel, but didn't seem perturbed. The journalists were just doing their job, he said. The hard part was telling his family.

“I’m not used to telling people my problems,” he said. “I’m used to taking care of my problems without sharing.”

New York City was supposed to be a good place for immigrants. That’s at least what he heard from his relatives and another friend from back home who now lives in Kentucky. Even newcomers could get health insurance and an I.D. He thought he would have a place to stay — that he’d be fine, even if he didn’t have a job.

I’m not used to telling people my problems. I’m used to taking care of my problems without sharing.

Moris, asylum-seeker from Senegal

Earlier this summer, Moris said, his uncle bought him a plane ticket from Senegal to Mexico after rioters from the ruling political party burned down his store, where he sold foreign-made accessories.

Living in Senegal left him in a constant state of anxiety, he said, and he just came here to be at peace. But although he feels safer from the threat of political persecution, he still hasn't found that peace.

In the mornings, he would visit restaurants and businesses to ask for a job, in Times Square, or around his last temporary shelter in Long Island City. Managers usually told him to leave his number. But no one has called back.

Now, the rest of his time is spent in the confines of the shelter’s clusters of massive white tents, or sitting with Senegalese friends on the stone benches in the park just across the street, where dozens of other migrant men congregate to pass the time.

“I don’t feel comfortable,” Moris said. “I will feel comfortable after I start working.”

Gregory, 27, Venezuela

When Gregory arrived at the Roosevelt Hotel, he received a warning from the other Venezuelan men he met: Don’t let people film you.

They described a bad experience – commenters on a social media interview they did had called them ignorant and lazy.

Gregory spent time outside of the Roosevelt Hotel, amid all the media buzz, but never spent the night on the sidewalk outside.

But, he said, “I’ve slept in worse places,” with “bad people that in any moment can kill you right there.”

Gregory said he had been beaten by a police officer back in his town in Venezuela, who was upset that Gregory had been dating his sister and his girlfriend. He said he had also been chased by cartel members in the mountains.

He said 30 of his friends in Venezuela had died at the hands of police.

“The worst day was the day I said goodbye to my son,” he said. “I never cried more.”

Nowadays, Gregory’s almost done with a construction certification class, which he hopes will give him an edge in the job market.

Inside the cluster of massive white tents where he now lives, some men complain about the food and lack of privacy. But Gregory said he had nothing to complain about. It had all the resources he needed, as well as good Venezuelan food, because of the Venezuelan cooks.

But in the long term, he doesn’t want to live in a shelter, where he'd sleep on head-to-toe cots, go to the bathroom in a trailer and rely on someone else to keep the lights on.

He came with other goals. He wants to get a job, all his legal documents, and settle down in an apartment he can rent by himself. And one day in the near future, maybe bring his family here. Or if he can’t, then take a plane to visit them back home.

When asked about his next steps, he said, “Whatever God wants. Whatever God wants.”

Mbacke Thiam, from the African language co-op Afrilingual, translated in French and Wolof.

For migrants in NY, stays in some city shelters have hit rock bottom, advocates say Awaiting help from city, 150 migrants sleep outside Manhattan’s Roosevelt Hotel Migrants cleared from sidewalk of Manhattan's Roosevelt Hotel