What New York’s Offshore Wind Expansion Could Mean For Your Electricity Bill, Curbing Emissions, And Your Health

April 7, 2021, 2:51 p.m.

President Joe Biden’s expansion of wind turbines off the East Coast effectively means New York can achieve its recently ratified climate goals.

New York is on track to become a centerpiece for the nation’s offshore wind industry after President Joe Biden announced last week that the waters off the coast of Long Island and New Jersey—the New York Bight—would be a designated wind energy area.

The president’s commitment, in which the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) sets aside more areas of the ocean to lease for offshore wind development, effectively makes it possible for New York to achieve its climate action goals, which the state codified two years ago in landmark legislation. By 2035, the state aims to produce 9 gigawatts of offshore wind energy under its Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.

The New York State Energy Research & Development Authority’s acting president Doreen Harris said the “magnitude of the opportunity” gets lost in the jargon used. The 9 gigawatt (or 9,000 megawatts) requirement in New York amounts to keeping the lights on for 6 million homes, or 30% of New York’s electricity.

“What that represents is a wholesale change—not only in our energy system in the electrons that are serving you and me in our homes, but the broader opportunity that it represents from an economic development perspective,” Harris said.

The president's plan cites an August 2020 study from the energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, which pushes the New York Bight’s potential to 11.5 gigawatts, 25,000 development and construction jobs between 2022 and 2030, and thousands of other jobs in operations and maintenance.

BOEM will also start reviewing the environmental impacts of New Jersey’s first offshore wind project, Ocean Wind, a critical launching point. New Jersey has pledged to install 7.5 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2035.

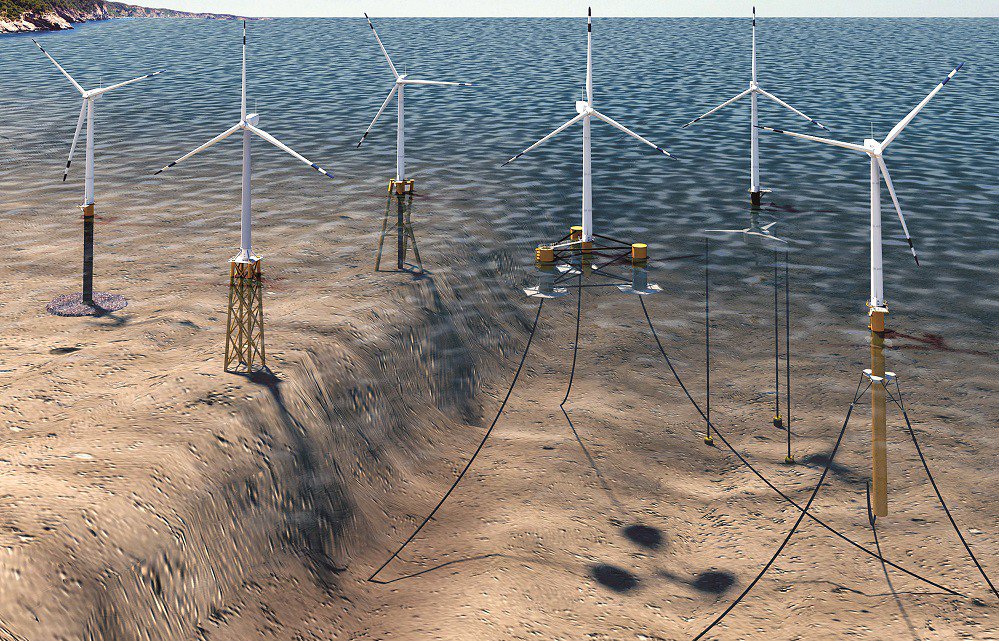

The only operating offshore wind farms in the U.S. are a 0.03-gigawatt plant with five turbines called Block Island, off the coast of Rhode Island, and a two-turbine operation off Virginia’s coastline.

Before Biden’s announcement, New York already had about 4.3 gigawatts of offshore wind energy in the works—spread across five different projects that haven’t begun construction but for which the state has awarded contracts. Among those includes a recent deal with the energy giant Equinor that would result in hundreds of jobs at ports around the state, including in Brooklyn. But Biden’s announcement ensures more leasing areas would be available for offshore wind activities.

“That wind energy area is the key component of it,” said Joe Martens, the director of the New York Offshore Wind Alliance and former commissioner of the state environmental conservation department. “We just don’t get there without new lease areas available, so that’s the connection.”

Prior to Biden’s announcement, monthly electricity bills were projected to rise just 81 cents, or 1.1%, under the state’s original plan for offshore wind projects for 2021 and beyond. That’s according to a cost analysis conducted by NYSERDA in June 2020. Those numbers might rise slightly given estimates from the state’s leadoff solicitation process for the first two offshore wind projects under NYSERDA predict a 73-cent increase, but the costs of making clean energy are also expected to fall over time. The prices related to January’s deal with Equinor haven’t been published yet.

It’s not clear how Biden’s scale-up could impact New York’s electricity costs, due to the many variables that go into leasing new sections of the New York Bight, a NYSERDA spokesperson said. But they added the agency is “pleased with the momentum and scale of the new lease sale” and is confident it will “buoy this industry.”

Those marginal costs will also be largely offset by the reduced health impacts created by decarbonizing the East Coast’s energy system. About $700 million in health costs, specifically from hospitalization or premature deaths due to asthma and respiratory or heart disease, would be avoided from NYSERDA’s first two projects. The net benefits from reduced carbon emissions due to offshore wind through 2030 amount to $4 billion under an analysis of how to achieve the state’s 2019 climate act, which requires New York’s energy pool to be 70% renewable by 2030. That rises to $9.6 billion over the lifetime of the projects under the 2035 goals.

“Offshore wind is a huge slice of the electricity we need to generate to meet those goals,” Martens added. Biden campaigned on a pledge to reach 100% renewable electricity by 2035, but Congress has not made it law. House Democrats have introduced legislation to mandate it.

Costs in the offshore wind industry are dropping, too. New York’s first two offshore wind projects yielded energy certificates that utility companies buy from NYSERDA to source electricity from renewable sources. Those certificates were nearly 40% less expensive in 2019 than predicted a year prior.

“That was a huge game-changer for us,” Harris said.

Offshore wind cost reductions in Europe are also encouraging the prospects for the industry here. “The offshore wind industry is booming in Europe, and we’re benefitting a lot from the cost reductions that have been seen from that scale, and now we’re reproducing that scale here in the U.S.,” Harris said.

The White House also announced that $8 million would go towards 15 new research projects, funded by NYSERDA and the federal Department of Energy under the National Offshore Wind Research & Development Consortium. Those efforts will study supply chains, structures and wildlife. Three projects are in New York.

Biden’s announcement represents a new commitment and a signal that governors in the Northeast have a partner in Washington D.C. to get it done, Martens said. Governor Andrew Cuomo said in a statement that Biden was “removing the barriers” put in place under former President Donald Trump, who had stalled offshore wind projects and, before becoming president, fought a wind farm planned for a site near his luxury golf course in Scotland, claiming it would be an eyesore.

Other critics worry about the construction along the shorelines. As The Guardian has reported, wealthy property owners in the Hamptons want to halt offshore wind development due to an underground cable that would be required to deliver electricity from windmills to the grid. The cable would run through beaches and beneath streets in a wealthy enclave of Long Island, which opponents claim will erode the beach and cause noise and fumes.

A coalition of fishing industry groups, the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, also questions the rapid development of wind energy and its impacts on scallops, squid and other marine life. The group accused the Biden administration of ignoring the fishing industry in the process.

“Offshore wind energy development poses an enormous risk to the marine environment and sustainable U.S. seafood production,” a statement from the group reads. “The Biden Administration’s disappointing fervor over its advancement continues an ineffective approach toward addressing climate change begun by previous administrations without demonstrating any willingness to include fisheries, ecosystem science, or our coastal communities in climate solutions.”

But, environmental groups like the Sierra Club and the National Audubon Society support wind energy, though they emphasize wind farms should be sited and planned to avoid harming birds and bats. Shay O’Reilly, a New York City-based organizer with the Sierra Club, added that offshore wind development is an opportunity to build out a new manufacturing industry.

“These are very, very large turbines with a lot of parts, and you're going to need a local supply chain,” O’Reilly said. He added that a major threat to the fishing industries is climate change itself—which is heating oceans and sapping their oxygen.

“We also really need to address climate change if we’re gonna have any fish left at all in our ocean,” O’Reilly said.