These landlords promised to house dozens of once homeless New Yorkers. Now they’re evicting them.

May 27, 2025, 6:30 a.m.

Supportive housing providers receive city and state funding to house formerly homeless residents, some of whom have mental health issues.

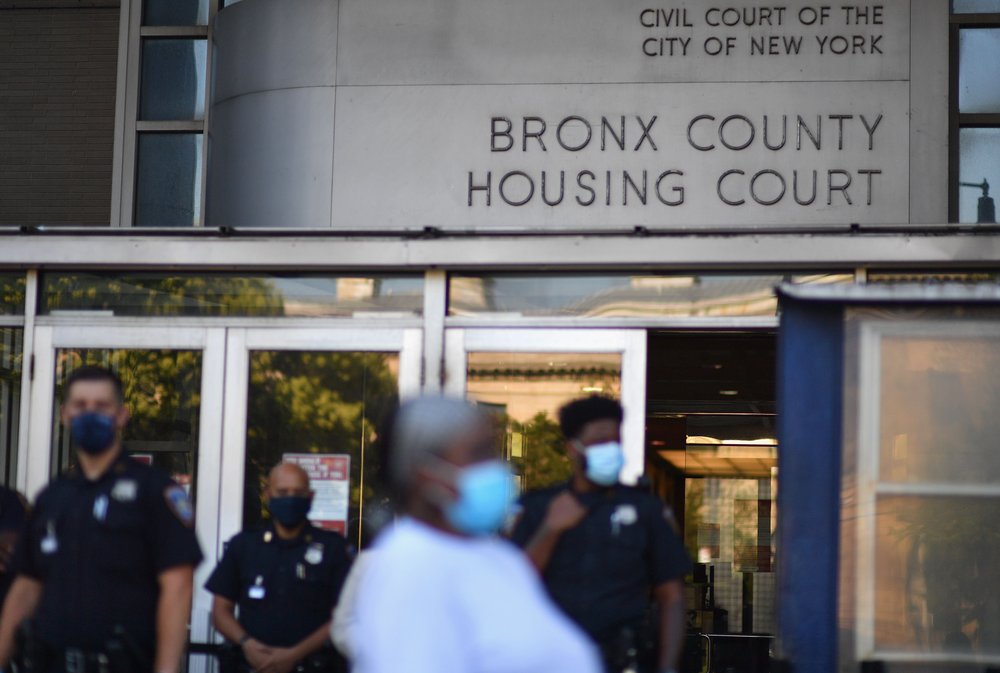

Landlords who get public money to house the most vulnerable New Yorkers — including people who were recently homeless and those with mental illness and substance abuse disorder — sought eviction warrants for nearly 300 people this year, a new analysis of the data shows.

The numbers are the first ever comprehensive look at how many marshal’s notices are issued by dozens of supportive housing providers, who receive city, state and federal money to provide housing to people in need. The data was compiled by Legal Services NYC, a nonprofit that provides free legal representation to low-income New Yorkers, and shared with Gothamist. The numbers were compiled through a review of daily marshal’s notices collected by the city’s Department of Investigation.

At least 293 tenants in supportive housing, which are subsidized apartments that come with additional social services, have had eviction warrants issued by a judge in the last five months, according to the data. The warrant authorizes a marshal to remove a tenant from a unit. Of those, 51 have so far lost their homes, Legal Services NYC found. Most of the cases were over unpaid rent and involved about 70 providers. The group said the numbers are likely an undercount because many providers sue through subsidiary companies or don’t disclose it’s a supportive housing unit.

Advocates, city officials and nonprofit providers agree supportive housing is a crucial part of the safety net that keeps people from returning to shelter or the streets. But as the industry has grown by 10,000 units in the last decade tenants and their advocates say too many New Yorkers aren’t receiving the help they need to hold on to their hard-fought housing — at a time when the city is desperately trying to reduce record homelessness.

“ There's no earthly reason why the government who is funding these supportive housing providers should not put in their contract that the provider has to do more,” said Pavita Krishnaswamy, supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society.

“You've worked so hard to get these folks off the streets into stable housing and then you don't require the providers to do everything in their power in return for the money that we're giving them to keep them stably housed.”

Tenants, who pay 30% of their income toward rent, say nonprofit providers promise to support them. But some say once they move in they don’t always get the help they need from their case managers or nonprofit staff to stay on top of their rent. And because many have a mental illness, they say, their requests for help are brushed off.

“ A lot of people don't deem us as credible,” said Charles Hart Jr., who got an eviction notice at the Bronx apartment that he’s lived in for 14 years after his health issues caused him to fall behind on rent. “We can’t be looked at any less than human, we have to be respected.”

Hart is still fighting his case in court.

A “painful choice”

Supportive housing landlords say the system works to keep the overwhelming number of the residents across 42,000 supportive housing units housed.

Supportive housing can look one of two ways: either in group living situations where the building is usually owned and operated by a nonprofit organization, or in scattered sites, where the nonprofits lease units on the private market.

The same nonprofit organizations contract with the city to provide voluntary services to tenants such as counseling, addiction treatment, job training or benefits that will help them remain stably housed.

For the small fraction they take to eviction court, they say it’s a “painful choice” of last resort needed to ensure their buildings and operations can keep running for other residents.

Pascale Leone, executive director of the Supportive Housing Network of New York, an organization representing 200 providers statewide, said an eviction “remains a tragic and very rare occurrence. Providers do everything possible to avoid it — offering case management, financial counseling, and repeated, tailored interventions.”

“But in a small number of cases, after months and years of outreach and support, some tenants remain unwilling or unable to pay rent or even engage in a payment plan or application for financial assistance,” Leone said. “In these instances, providers face painful choices to protect their buildings and ensure the vast majority of tenants can remain safely and stably housed.”

The network doesn’t track evictions.

Providers also say moving toward eviction is also a way to compel the city to fast-track emergency rental assistance for tenants; an eviction filing will often move an application for crucial rental aid to the top of the pile, they say.

The Jericho Project said they make sure to let tenants know the eviction warrant is just part of the process to get them assistance. But city officials were adamant that tenants don’t need an eviction to receive rental assistance and discouraged using evictions in this way.

”We try to think of it as two sides. We have the operation side where they're pursuing the eviction because you have to pay rent, that's your obligation. You signed a lease,” said Tori Lyon, CEO of Jericho Project. “And then on the other side we have the social services.”

“ We do everything we can to keep people housed,” she said, adding that it would help if the city could expedite issuing one-time rental assistance deals to tenants before landlords are forced to file an eviction.

Some supportive housing providers say they are struggling financially given mounting rental arrears that have accumulated since the pandemic.

Brenda Rosen, president and CEO of Breaking Ground, said half of their tenants are behind in rent but a vast majority “work with our onsite social and supportive service providers to address their back rent, including payment plans as low as $19 a month.”

“Due to our team’s extraordinary efforts every day, only one tenant in supportive housing, who had not paid rent for four years, has been evicted for nonpayment over the last 12 months,” Rosen said.

‘I’m in supportive housing with no support’

Tenant advocates, who have long raised concerns about evictions, say providers are too often using the courts as an arm of their case management. They said they should work with tenants to secure public benefits that can help them pay their rent, instead of turning to the courts to compel residents to pay up or leave.

Craig Hughes, a social worker for Legal Services NYC, said tracking evictions will strengthen the supporting housing system. “We can't do that if we're just pretending a problem doesn't exist,” he said.

”Once someone's in supportive housing and they fail to get the support that they need…they're gonna end up in the shelter system. They're gonna end up on the streets and it's going to take them years if they ever get out.”

Kat Corbell, 46, said she had been trying to figure out with her supporting housing provider how much she needed to pay toward rent and whether her internet bill counted toward her contributions. But her provider, The Bridge, took her to court for owing $5,200. The Bridge didn’t respond to a request for comment.

She said she was told by her provider “when you hear from our lawyers, don’t be scared” and that the case would help her get emergency rental assistance from the city. “‘It's just what the city's requiring us to do,’” she recalled hearing from her provider.

“If I ever needed help, they would just always ask me to Google it,” Corbell said. “ I get more support from like my doctor's office for instance, because they were able to help me sign up for the meal delivery during COVID.”

Attorneys also flagged another issue: Landlords are routinely failing to disclose to judges that the tenant is in supportive housing, which may entitle them to additional resources such as Adult Protective Services or a guardian ad litem.

If a judge doesn’t know a tenant may have a disability or mental illness, they could more quickly issue a judgement against them for not appearing in court, lawyers said.

Hart, 59, struggled with health issues which caused him to fall behind on his rent. He said the mold in his apartment has worsened his chronic health conditions. His landlord, the Postgraduate Center for Mental Health, sued him for $10,900 in owed rent, court records show, but didn’t disclose the unit was supportive housing. The Postgraduate Center for Mental Health didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“Tenants can’t get heard. Nobody wants to take the initiative, nobody wants to reach out to tenants,” he said.

“I will face significant hardship if I lose my home; I have nowhere to go if I am forced to leave,” he wrote in court records.

In another case where the landlord didn’t disclose they were suing a supportive housing tenant, the city intervened to stop the eviction, writing the tenant’s “health is such that she cannot adequately defend her tenancy rights and the court is urged to use its statutory powers to appoint a guardian ad litem.” In another, a tenant said they missed the court date because she had the wrong date and wrote in the court record: “I’m in supportive housing with no support.”

Lasting consequences

There’s no citywide database on tracking supportive housing evictions, partly because a patchwork of agencies including the city’s health department and the state’s Office of Mental Health, oversee providers. The city’s Department of Social Services, which oversees social services, says it’s building a tracking system to track eviction warrants and identify at-risk tenants. The agency is also considering tightening its contracts to make eviction a last resort.

“Supportive housing providers are mission driven organizations who serve some of the most vulnerable New Yorkers, and the continuity of their services depends on their overall financial stability,” City Hall spokesperson William Fowler said.

He said the Adams administration is proposing more money to increase subsidies for supportive housing units.

Fowler said it was important for providers to stop using evictions to secure emergency rental aid and that “agreeing on this is essential in preventing our most vulnerable New Yorkers from ending up on the street.”

On any given day there can be 150-400 marshals notices issued, attorneys said. But the smaller number of warrants of evictions in supportive housing can have much more devastating consequences.

“ The most vulnerable people in this situation are being used as pawns for what is basically a transfer of funds from the city to the provider. That makes no sense. They should not be suing these people for nonpayment,” Krishnaswamy said.

4th-generation resident of rent-stabilized Manhattan apartment fights eviction Middle-income New Yorkers are the new face of eviction in the city, report finds