The African American exodus from New York City

Feb. 3, 2023, 5 a.m.

While the city’s overall population grows, the number of non-Hispanic Blacks continues to tumble; an epicenter of the change is Bed-Stuy.

Faith Robinson can count on one hand the number of Black families from her childhood who still live on her block in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Most of the 27-year-old’s neighborhood friends moved out of the city.

There are unmeasurable other neighborhood changes – as with the block parties, which she and other longtime residents say aren’t the same anymore. “The vibe is just so off these days,” said Bahamian-born filmmaker Sekiya Dorsett, who has lived in the neighborhood for over 10 years.

Once called the “Little Harlem” of Brooklyn, Bed-Stuy is one of the epicenters of what is being described as a mass migration of African American residents out of New York City. The trend is part of a broader African American exodus away from urban areas across the North and West and into smaller cities, suburbs, and – in a reversal of the 1910-to-1970 “Great Migration” – the South.

In this vintage photograph, children participate in the International African Arts Festival in front of the community center that was home to The East, a pan-African cultural organization founded in 1969 by teens and young adults in Bed-Stuy.

Even as New York City’s population continues to grow, and the Afro-Latino community expands, the number of non-Hispanic Black residents has declined by more than 125,000 in the last 20 years, a more than 6% decline, according to a Gothamist analysis of 2000 to 2020 Census data. The majority of this decline comes from the city’s shrinking African American community – the U.S.-born descendants of enslaved Africans, according to local social scientists. But the city’s population of continental Africans and Black West Indians have also shrunk in recent years.

The decline in the non-Hispanic Black population in New York City is one of the largest among major cities nationwide, trailing only Chicago and Detroit, and portends what many residents, demographers and others see as vexing cultural, political and economic challenges ahead. Some observers say the changing demographics prompt an uneasy question about whom New York City is really working for.

“These are not just issues that are persistent in the Black community in Brooklyn,” said L. Joy Williams, president of the Brooklyn chapter of the NAACP. “They are issues of working-class and poor people across the city.”

The reasons African Americans are leaving New York in such large numbers are complex and run the gamut. Demographers note that the aging population has something to do with it — and that some African Americans leave to stretch their retirement dollars, escape high taxes, and find better opportunities elsewhere, just as other groups do.

But researchers also point to a housing crisis that has spurred endless neighborhood squabbles over affordability and whether more should be done to preserve housing for those at the lowest income levels. And even as the city’s economy has added more high-paying jobs, they say African American New Yorkers overall have seen limited economic gains and job opportunities compared to other groups.

“People still love New York,” said Zulema Blair, CUNY Medgar Evers College chair of public administration who studies the city’s changing Black population. “But it's not a place that they feel that they can thrive.”

Over time, the decline in the city’s African American population could have implications in terms of political representation and the city’s leading role in setting the agenda in Washington for cities across the nation. And some fear a loss of local African American cultural institutions, landmarks and a sense of community.

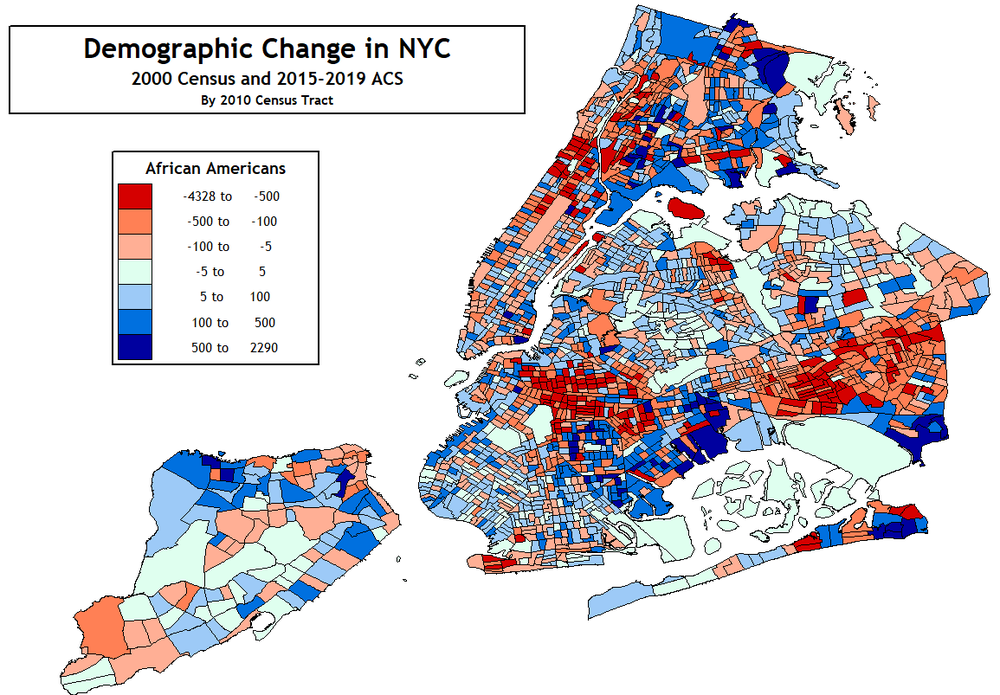

While outer boroughs and neighborhoods saw modest increases in their non-Hispanic Black populations – like parts of the Bronx, Staten Island, and Canarsie in Brooklyn – the greatest losses were in northern Manhattan, southeast Queens, and central Brooklyn, according to a report on the latest census data from the Department of City Planning.

Meanwhile, the city’s growing population – at 8.8 million in 2020, up nearly 8% from a decade prior – has been fueled by an influx of Asian and Latino residents. The Black population of Harlem has been on the decline after peaking in 1950, spurred by a mix of suburbanization, urban renewal and housing pressures. The drop has continued in recent years as gentrification has taken root, leaving the neighborhood no longer majority Black by 2010.

But the greatest shift in the last 10 years has occurred in the more recent Black mecca of Bed-Stuy – located just a few blocks north of what was one of the largest free Black communities in the antebellum U.S. – whose Black population grew with the Great Depression and the creation of the A train in the 1930s.

The 1936 extension of the eighth avenue express played a major part in establishing Bed-Stuy as Brooklyn's central African American community; the borough's "Little Harlem."

In the last decade, Bed-Stuy lost over 22,000 non-Hispanic Black residents, the most of any neighborhood citywide. Over the last 20 years, from 2000 to 2010, that community shrunk from making up nearly 75% of the neighborhood to less than half. At the same time, the area’s median household income nearly doubled. The poverty rate dropped from over a third of the population to about a quarter, according to data from the Furman Center at NYU.

As the city’s African American population ages, and rents and property prices climb, community leaders are fighting to preserve local history, create new community spaces, and keep the neighborhood affordable for younger generations as greater numbers of wealthier white residents move in. But Black longtime residents say it’s been an uphill battle.

‘Never in a million years’

Robinson, a daycare worker, wants to settle down in Bed-Stuy, where her mom has lived for over 60 years, and buy her own brownstone like her mom, but the changes in her neighborhood have left her wondering what’s ahead.

Faith Robinson, whose family has lived in Bed-Stuy for multiple generations, hopes to stay in the neighborhood.

Just a few blocks from Robinson’s home – on Tompkins Avenue, a central commercial artery in Bed-Stuy – a window banner recently announced a new store “NOW OPEN,” with logos beneath for Cinnabon and Carvel. “Never in a million years” would she have imagined a Cinnabon opening in her neighborhood. Maybe in Downtown Brooklyn, but not so close to home.

Longtime Black residents say they also enjoy the new neighborhood cafes, and acknowledge that some amount of change is normal. But many add that they feel the new amenities aren’t intended for them and that the newcomers haven’t integrated into the culture of the neighborhood.

To preserve and celebrate Bed-Stuy’s history, Robinson started an Instagram account called “Bed-Stuy Forever,” which she considers an archive of and love letter to her neighborhood. It’s a reminder of the landmarks and cultural institutions that once dotted the neighborhood before an influx of high-rise condos and national chains.

Robinson’s love for going through old family photos motivated her to start her instagram archive page, @BedStuyForever.

“For my nana’s generation, it was a struggle to get what they needed for the neighborhood,” Robinson said. “It feels like we can’t have a piece of the new things coming around.”

Relocated to North Carolina

When the coronavirus pandemic mandated the closure of all “non-essential businesses” in March 2020, Anthony Lewis Cunningham and his wife closed the doors of Kafe Louverture, the Bed-Stuy restaurant that some diners claimed served the best Haitian patties in all of New York City, and the eatery remained shuttered.

Anthony Lewis Cunningham and his wife, Joanne Saget, in their backyard in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. The couple -- and owners of a heralded Bed-Stuy restaurant -- relocated in 2020, following the initial COVID-19 shutdown.

The East New York native, who grew up in the Cypress Hills public housing community, and his Haitian-born wife relocated to the central North Carolina town of Rocky Mount – population of about 50,000 – where they plan to reopen the restaurant in the spring.

Cunningham had always wanted to move down South. His great-grandparents moved from South Carolina to Bed-Stuy in the ‘50s. And the 46-year-old remembers childhood summers spent visiting relatives in South Carolina, jumping on trampolines, watching trains pass by, going to cookouts and drinking tea on the porch with his great uncle. He’d always craved the “little things” about country living – a “different quality of life,” as he put it.

“New York City’s a rat race, so you have to become a rat,” he said. “And you have to stay on that treadmill.”

He added: “At some point in life, you have to find peace.”

The duo plans to reopen Kafe Louverture -- in North Carolina -- in the spring.

Cunningham’s story is not uncommon. The city is a net exporter of domestic migration, and it’s common for older residents to move away, said John Mollenkopf, director of the Center for Urban Research, CUNY Graduate Center.

Henry Butler, district manager of Community Board 3 in Bed-Stuy, says he knows several neighborhood retirees and young college graduates who have chosen to relocate to the South.

“There's a good amount who are leaving ‘cause they choose to leave,” Butler said. He later added: “That’s never part of the conversation.”

It’s unclear just how many African Americans are displaced or instead choose to leave. But many longtime Bed-Stuy residents have been forced to move out, researchers and residents alike acknowledge. The neighborhood was home to some of the highest foreclosure rates in the nation from the subprime mortgage crisis that fueled the 2008 Great Recession. And it’s also been a hotspot for deed-theft, in which homeowners are scammed into signing over their homes, a practice that has disproportionately harmed Black people and other people of color. Median rental prices have also surged -- at times above the citywide median -- to nearly $3,000, according to data from real estate search engine StreetEasy, up by more than 80% in the last 12 years.

The “promise” of Northern cities like New York that once lured former slaves and their descendants is fading, says Brookings urban demographer William Frey. Deindustrialization killed or relocated blue-collar jobs often filled by Black city dwellers by the 1970s. Black residents increasingly lived in under-resourced, segregated areas, and “white flight” shifted jobs and tax dollars further out of reach.

“What does the quality of life depend on?” Blair said. “Income. What bang you're getting for your buck.”

Despite New York City’s status as a leading tech hub and longtime financial and cultural center, non-Hispanic Black residents hold “a shockingly small share” of the city’s jobs across several well-paying industries, the Center for an Urban Future found. Stark wage disparities persist even within the same industries. Black and brown New Yorkers are also underrepresented in accessible, middle-wage jobs, including food manufacturing and in doctor’s offices, according to the center’s research.

Further, New York state has among the highest degrees of income inequality across the country, and from 2014 to 2018, Black workers’ earned two-thirds of white workers’ average annual salaries. In New York City, incomes for African Americans have remained stagnant even as those of other racial and ethnic groups are increasing, Blair says. And the city’s rates of African American homeownership – heralded as a key to building intergenerational wealth and avoiding displacement in gentrifying neighborhoods– have also shrunk.

Some of the economic disparities are tied to education. The Center for an Urban Future found that just over a quarter of Black non-Hispanic New Yorkers have bachelor’s degrees, compared to the citywide average of 40% and 64% for white New Yorkers. And many of the city’s high-paying jobs require advanced degrees or specialized skills that many African American residents don’t have, said Lance Freeman, a University of Pennsylvania sociology and urban planning professor who has studied gentrification in Black New York City neighborhoods.

“The economic opportunity is not perceived to be what it was, given the high cost of living in New York City,” Freeman said.

Disappearing Black spaces

Herbert Von King Park – a few blocks north of the new Cinnabon on Tompkins Avenue – has become a symbol for some Bed-Stuy natives of how the neighborhood has changed.

Citing overcrowding and bicycles zooming by, some seniors no longer feel they have a space in the park, Councilmember Chi Ossé said. The grassy lawn is filled with young white adults spread out on picnic blankets, throwing Frisbees, and walking their dogs – sometimes off-leash, seniors complain. That wouldn’t be the case 15 or 20 years ago, Butler added, when the park was mostly frequented by Black residents hosting barbecues, playing basketball, and listening to music.

“Go there on a Saturday, Sunday afternoon, you’ll swear you’re in Prospect Park or Central Park,” Butler said.

On Fulton Street, a central thoroughfare along the neighborhood’s southern border, Robinson can cite several gathering spaces that no longer exist: a McDonald’s sells Happy Meals at the same address where James Brown once performed at the neighborhood’s own Apollo Theater; while a few blocks west, a defunct record shop stands where the anti-poverty group Youth in Action, formed in the ‘60s, once hosted after-school activities and Shirley Chisholm, the nation’s first Black congresswoman, would sometimes visit.

And farther west and less than a block north, the building that used to be the headquarters of The East, a Pan-African group founded in 1969, has been transformed into a 10-apartment complex. On the first floor was a jazz club where Sun Ra and Gil Scott-Heron once performed, and the same building housed an all-ages school called Uhuru Sasa Shule, Swahili for “Freedom Now School.”

In this vintage photograph, students of Uhuru Sasa Shule -- "Freedom Now School" in Swahili -- in front of The East.

“That school was very needed to tell these children that they're Black, they're beautiful,” Robinson said, adding that she wishes more neighborhood spaces existed for Black youth empowerment. “You can be a lawyer, you can be a doctor, you can be anything that you want to be.”

Longtime residents say they also worry about the fate of local landmarks as the neighborhood continues to change.

On a street corner once frequented by the late rapper Notorious B.I.G., a landlord six years ago threatened to tear down a two-story mural painted in honor of the neighborhood icon.

“Why should I keep it?” Solomon Berkowitz told DNAinfo in 2017. “I don’t even see the point of the discussion.”

While the Biggie mural has survived, other notable properties have been lost.

One morning last July, Joanne Joyner-Wells and a crowd of her neighbors and local politicians watched from a nearby sidewalk as a demolition machine clawed bricks from a 120-year-old French Gothic mansion. Suddenly, the multi-story tower toppled to the ground in a cloud of dust.

Joyner-Wells, a Bed-Stuy native who has lived on the block for some 60 years, said it was a gathering place “for communities of color.” At the “Willoughby Temple,” as it used to be called, neighbors attended Boy Scout gatherings, block association meetings, and even Joyner-Wells’ and her parents’ wedding receptions. Now, it’s just an empty lot with a chain link fence.

“It makes me feel a little lonely,” she said of the departure of many African American neighbors. “Because I have no intention of moving.”

At 24, Ossé is one of the youngest people ever elected to the City Council, and is its only member from Gen Z.

“We're not going to be able to pass down these stories and also continue to create and cultivate this safe Black community that Bed–Stuy has been and hopefully will forever be,” said Ossé, whose district includes much of Bed-Stuy.

Some longtime neighborhood haunts hang on, like the more than 50-year-old Restoration Plaza, home to the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, one of the first community development organization in the country.

The Brownstoners of Bedford-Stuyvesant also organize an annual self-guided house tour – now in its 45th year – with proceeds going toward college scholarships for three students in neighborhood schools.

Community organizer Kendra J. Ross founded STooPS Bed-Stuy as a way to get to know her new neighborhood after moving from Detroit.

But as old institutions are lost, new ones spring up, like arts organization STooPS, which was formed in 2013 to build community and fight the effects of gentrification in Bed-Stuy. But these organizations aren’t immune to the economic and housing pressures driving residents from the neighborhood. STooPs founder and director Kendra J. Ross, a 37-year-old Detroit native who’s lived in the neighborhood since 2009, said she almost had to move away in 2014 when her landlord kicked her out.

She said, “I kind of feel like I’m always hanging on by a string.”

The political consequences

To see the ascendancy of African American political power in New York, look no further than Mayor Eric Adams, local politicos say. Black elected officials also hold key leadership roles in City Council and the state Legislature, as well as other high-profile positions. Attorney General Letitia James and Brooklyn Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, the new leader of House Democrats in Congress, are both African Americans.

But some fear that the city’s demographic shifts could mark this moment as a peak of local African American political power. That could mean less representation, less funding and less attention to policymaking aimed at addressing traditional urban woes.

“It means more sidelining of an African American agenda,” said Blair.

Local elections and redistricting battles reveal the evolving struggle for political power among the city’s diverse, mostly non-white communities.

The 2016 triumph of Adriano Espaillat, who is Dominican American, in the race for the 13th Congressional District representing Harlem and Upper Manhattan incited fears of declining African American political power among local Black leaders, DNAinfo reported. Espaillat, a self-described “Latino of African descent,” defeated then-Assembly Member Keith Wright and replaced Rep. Charles Rangel, both African Americans.

In Southeast Queens, where the South Asian population has multiplied as the African American population has shrunk, new draft electoral district maps released last fall incited clashes. Community groups representing the growing South Asian population argued the maps would further dilute and divide their political power. In a letter to the redistricting commission, several elected officials in the region’s majority-Black districts made a similar argument for local Black voters, noting the districts’ creation in the ‘90s to increase Black representation.

And while more Afro-Latino and immigrant newcomers have bolstered the city’s overall Black population, which has remained relatively stable in recent decades, different Black communities’ interests sometimes diverge. Black immigrants - like all immigrants - are a subsection of foreigners willing enough and able to muster the resources to move, said Christina Greer, a Fordham University political science professor studying local Black politics.

Specific interethnic dynamics depend on the neighborhood and group size, she said, but tensions have emerged among different Black populations over perceptions of scarce resources, like in education and housing.

“At the end of the day, people start going to their little subsets and their subgroups,” said Butler, Bed-Stuy’s community board district manager. He added: “There should be an overall Black agenda.”

He emphasized the importance of policies specifically targeted at improving outcomes for Black residents, rather than “people of color” more broadly. Whether getting pulled over by police or applying for a bank loan, he said, “The very first thing they see on you is the color of your skin.”

Greer also warns that the financial pressures pushing and pulling African Americans from the city aren’t unique to that group.

She said: “Black people are the canaries in the mine.”

“We're the ones who bring up issues that end up helping everyone,” she continued. “We don't necessarily see that in the reciprocal. We don't.”

This article was updated: Additional information was included about the vintage photographs that appear.