‘Shrinking my world really small’: How New Yorkers are coping with long COVID

March 31, 2025, 6:33 a.m.

An estimated 500,000 New Yorkers suffer from COVID’s lingering effects, with 1 in 5 saying the condition significantly limits their activities.

On a pleasant March morning, Alisha laid on the exam table in her doctor’s sunny office in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, and reflected on the arrival of another post-pandemic spring. “ It's another year of not fully being able to enjoy the city,” said the once-active 35-year-old, who asked that her last name be withheld to preserve her privacy.

Before the pandemic, Alisha had a marketing job at a cosmetics company and spent her free time exercising, baking and going out with friends. Since getting COVID at the end of 2020, she has been dogged by chronic fatigue and other long-term symptoms that prevent her from working or even walking to the end of her block on most days. Many of her outings involve commuting to doctors’ appointments like this one via Uber.

“People are out, people are excited,” Alisha said. “It's like the whole world is moving and I'm not moving like them.”

Five years after the pandemic first struck New York and the nation, Alisha is one of potentially hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers — researchers are unclear exactly how many there are — who are still slowed down by long COVID. Their condition is defined by symptoms that come on after an acute COVID infection and last for at least three months, and sometimes years. Although long COVID is a well-documented phenomenon, there’s still no diagnostic test to confirm its presence, meaning that symptoms are generally self-reported.

One of the most common reported symptoms is chronic, debilitating fatigue. That’s often paired with a punishing condition known as post-exertional malaise — a crash that comes after too much mental or physical activity. While the risks of severe disease often fall on the very young or very old, people in their 30s and 40s are at highest risk for long COVID, studies show.

“ We have, unfortunately, a large number of patients that cannot work,” and others who are only able to work part-time, said Dr. Fernando Carnavali, medical director of the long COVID clinic at Mount Sinai West.

Researchers and clinicians at Mount Sinai, NYU Langone and other major medical centers in the city are helping to lead the way in better understanding how long COVID works and which treatments might alleviate symptoms. Hospital-based long COVID centers direct patients to specialists and offer them ways to better manage their symptoms, which can include brain fog, shortness of breath, dizziness, heart palpitations and a range of other issues.

But, even as research advances, there are still competing theories as to the underlying causes, and no federally approved treatments are available. Some patients worry progress will falter under President Donald Trump. The Trump administration is reportedly eliminating a federal office dedicated to long COVID and abruptly terminating some long COVID research grants, amid broader cuts to COVID-related funding.

“ People are desperate for solutions,” Carnavali said, adding that patients often do their own research and experiment with remedies recommended by others online. Carnavali said his role is to help them be more strategic, and to rule out anything that might be unsafe.

Gothamist spoke with 10 New Yorkers with long COVID, all in their late 20s to early 40s. They said they were forced to drastically change their expectations for their careers and lives in New York City, while spending much of their time and money searching for remedies that might offer some relief. Some said they have seen improvements in their symptoms over time and have regained their previous capacity to varying degrees. Others said they are still largely bedbound and need help from spouses or other caregivers to get through the day.

‘I was hoping to progress further in my career’

Sometimes, Alisha can’t help but reminisce about what her life was like before long COVID. She pulls up pictures on her phone of her celebrating her 30th birthday with friends, cooking with her mom and hiking with her husband outside the city early in the pandemic.

“ When I think about five years, I just think about how different things would've been if I wasn't sick,” she said. “We planned to have a family. I was hoping to progress further in my career.”

While estimates on the number of people with long COVID vary, one large survey recently published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found about 6% of adults in New York state were living with long COVID in 2023, similar to the national rate. That amounts to about 500,000 people with long COVID in the five boroughs alone. Of those with long COVID, about 1 in 5 reported that it limited their activities significantly.

Alisha said she initially kept working after getting long COVID — typically, from bed because her fatigue was so bad. But at a certain point, she said she had to give it up and go on long-term disability. Now, much of her life is dedicated to managing her health.

For Alisha, the worst part of long COVID is the post-exertional malaise, or crash, that can come after extending herself even slightly beyond her limits. Alisha says even something simple, like watching an extra hour of TV, can set her back — a kind of “payback” for having a good time.

Carnavali said one of the most beneficial things he can do for patients with post-exertional malaise is teach them “structured pacing,” a practice of conserving their energy so they don’t crash.

Alisha said learning to pace herself has helped make her days more predictable and improved her quality of life. But, she added, it also meant “shrinking my world really small.”

She can now sometimes manage to go to a coffee shop with her husband on the weekend, or visit with family, but she said she has to save up her energy ahead of time and they always have to drive.

Some New Yorkers with long COVID say they’ve lost friends as they’ve become more limited in what they can do.

While there are many physical symptoms associated with long COVID, many patients are also struggling with their mental health and adjusting to having a disability, said Dr. Amanda Johnson, director of the AfterCare program serving long COVID patients at NYC Health and Hospitals.

By and large, these are patients whose identities were not previously based around being sick, Johnson said, “so this is really challenging for them.”

The search for relief

Long COVID patients who spoke to Gothamist said they’ve tried a wide range of experimental treatments and therapies to find relief, some of which are covered by insurance, but not all.

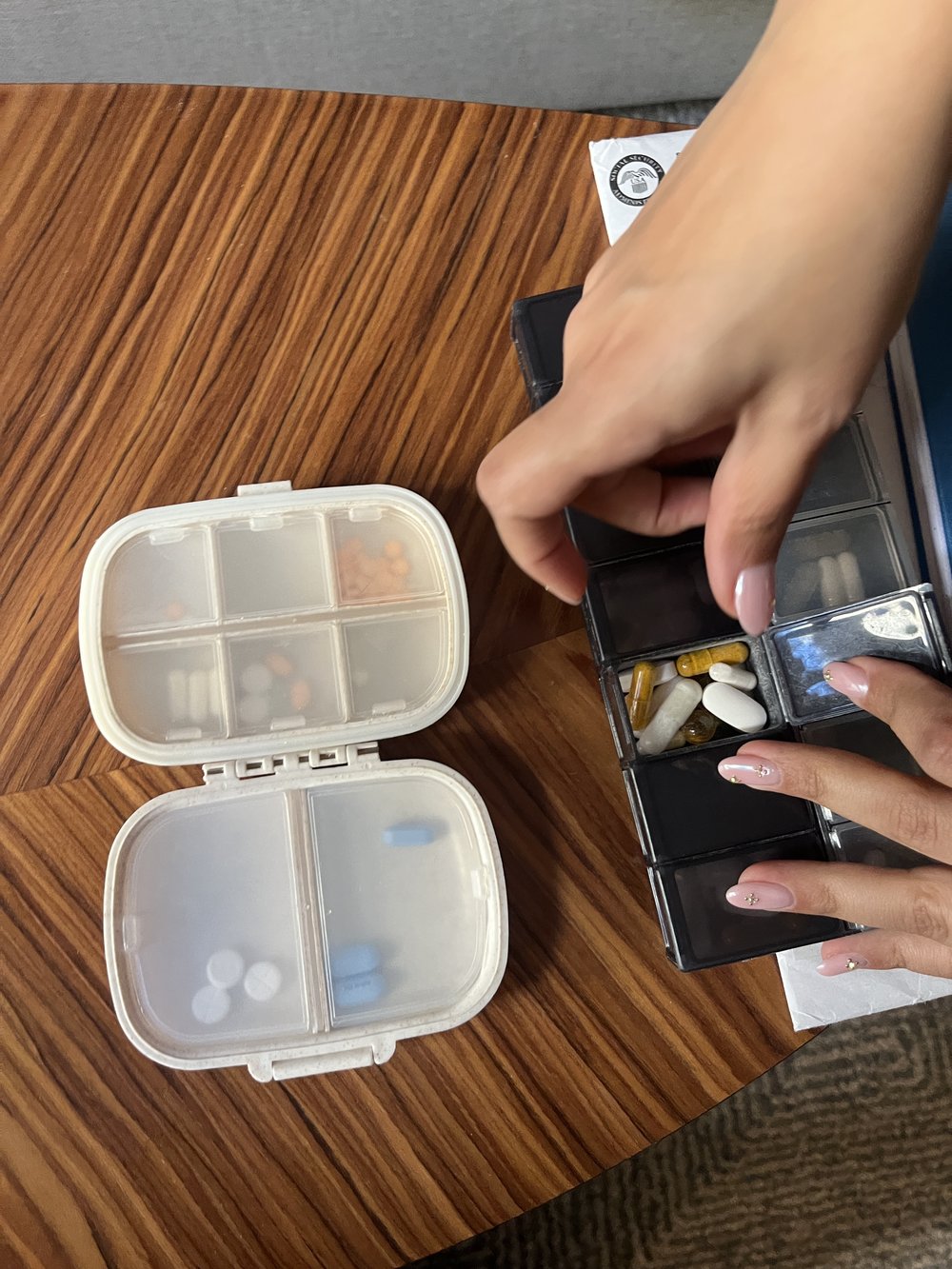

A drawer in Alisha’s bedroom is packed full of dietary supplements. She takes 10 to 15 daily — although she’s tried many more. She has also been prescribed some “off-label” medications that are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but were approved for a different medical condition.

One of those medications is naltrexone, an injectable drug that’s approved for the treatment of opioid and alcohol addiction, but which has been shown to help relieve fatigue and pain for some long COVID patients when prescribed at low doses.

Dr. Rebecca Summers, Alisha’s primary care doctor, explained that to get a low dose of naltrexone, she has to go to a special compounding pharmacy that makes customized drugs, and it isn’t covered by Alisha’s insurance.

Alisha has also tried alternative therapies, and said she has found the most success with somatic experiencing, a practice Summers offers that seeks to help people identify and relieve the effects of psychological stress and trauma on their bodies. That’s not covered by insurance, either.

“ Nobody really knows how to treat this thing, so you're just trying different healing modalities,” Alisha said. “In the last four years, we've probably spent at least $30,000 to $40,000, if not more.”

Alisha said she has help from her husband, in addition to savings and the income from her long-term disability benefits. But not everyone is in the same boat.

Nobody really knows how to treat this thing, so you're just trying different healing modalities.

Alisha, long COVID patient

Kelly Fioravante, a so-called “long-hauler” in Ridgewood, Queens, is a musician and sex worker. She said some of her care is covered by her Medicaid plan, but she has also turned to GoFundMe and her mom’s church to raise money for testing and treatments.

“All my extra money goes to medical care,” said Fioravante, 40, adding that she works much less than she did before developing long COVID in 2022.

Some patients get better over time — but life might not look exactly like it did before.

Journalist Erin Durkin stopped working after getting sick in 2022, but said her symptoms have since improved enough to freelance part time. Often, she works lying down because she suffers from heart palpitations when she’s upright, but she said she’s far from bedbound.

“ I can go out. I can do things. I can walk around. I can take care of myself,” said Durkin, who lives in Jackson Heights, acknowledging that not all long COVID patients can.

Still, Durkin is now much more cautious than most New Yorkers when it comes to COVID, out of fear of getting reinfected and making her symptoms worse. She always masks in public and will only eat at a restaurant if there’s outdoor seating, which is becoming harder to find.

Is help on the way?

Although there are no FDA-approved treatments for long COVID yet, Brooklynite Hannah Davis said she is encouraged by the fact that there is now widespread recognition of long COVID within the medical community and a rapidly growing body of research on how it affects the body.

But she said she worries about the potential impact of Trump’s cuts to scientific research.

Davis, 37, first developed symptoms of long COVID after catching the virus in March 2020, at the start of the pandemic in New York. She is one of the cofounders of Patient-Led Research Collaborative, which published early findings on the symptoms associated with long COVID after surveying hundreds of people online. The group has since advocated to advance research and patient care.

“ The thing we really need to be doing now is increasing clinical trials,” Davis said.

The RECOVER Initiative, a $1.6 billion long COVID research effort funded by the National Institutes of Health, has faced criticism from some patients for being slow to enroll people in clinical trials. But according to the RECOVER website, eight trials are now being funded that examine 13 possible treatments and therapies.

Many long COVID patients also receive other diagnoses that align with their particular symptoms, and some researchers say ongoing studies on those medical conditions could also benefit long COVID patients.

The Department of Health and Human Services did not respond to a request for comment on Friday on which long COVID-related studies have been affected by recent cuts.

"The COVID-19 pandemic is over, and HHS will no longer waste billions of taxpayer dollars responding to a nonexistent pandemic that Americans moved on from years ago," HHS Director of Communications Andrew Nixon said in a statement to NBC last week on the administration's decision to deprioritize COVID generally.

The administration is also eliminating the federal Office of Long COVID Research and Practice, which coordinates efforts across federal agencies, according to Politico. And last month, HHS was ordered to dismantle its Advisory Committee on Long COVID, made up of volunteer scientists, advocates and health practitioners.

In the meantime, patients like Alisha say they are doing whatever they can to find some peace and stability.

Alisha and her husband moved to their current apartment, just a couple of blocks from Prospect Park, in 2023 in hopes the urban oasis would be accessible to her — but she’s yet to visit.

That’s one of her goals this spring.

5 years since COVID struck NYC, a look at how it changed how we live and work Could Trump, RFK Jr. affect vaccinations in NY? Public health experts weigh in. Mt. Sinai opens long COVID center for NYC communities slammed in pandemic NYC COVID cases up 250% in 2 months — and this variant's harder to duck