Ruth Bader Ginsburg is first addition to Albany’s Million Dollar Staircase in 125 years

July 4, 2023, 6 a.m.

The Capitol’s famed staircase is home to carvings of 77 “famous” faces, not to mention more than a dozen others who are mysteries even to the building’s knowledgeable historians.

Metal scaffolding climbs its way up the reddish-brown sandstone that makes up the Million Dollar Staircase — an enormous, intricately carved, four-floor structure in the New York State Capitol in Albany.

This summer, for the first time since 1898, a new face is being added — Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the late U.S. Supreme Court justice born and raised in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Midwood.

The Capitol’s famed staircase is home to carvings of 77 “famous” faces, not to mention more than a dozen others who are mysteries even to the building’s knowledgeable historians, though most believe the unknowns are relatives of the original carvers.

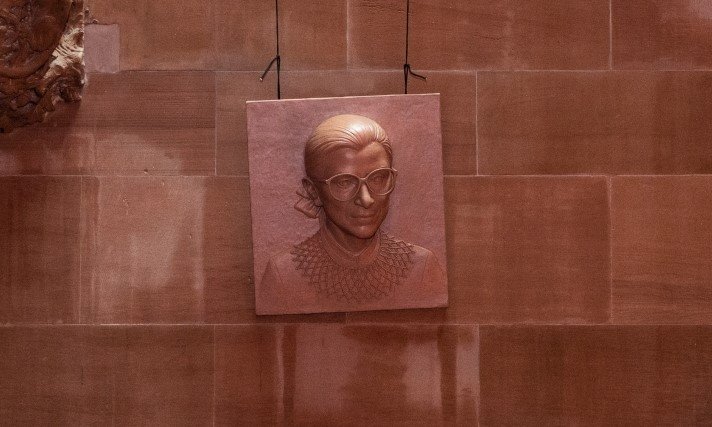

A carving of Ginsburg’s face and famed South African collar — the beaded white one she wore for special occasions — has already been installed between the second and third floor, though it remains blocked off from public view as stone carvers complete the inscription and do minor clean-up work. Gov. Kathy Hochul's administration is expected to officially unveil Ginsburg’s stone portrait in August.

In late June, a stone carver, Adam Paul Heller, stood on a flat surface enveloped by white tarps. He had a small satchel filled with chisels and tools, scissors and a brush hanging from a pole, a lamp straight from a Pixar movie and a foam mat for when he had to kneel. The scaffold floor was covered, which helped him forget he was 40 or 50 feet above the ground.

“It feels so safe because you can't see how actually high we are,” Heller said. The job is so meticulous that his current task of carving four words — Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg — had taken weeks of planning.

Ginsburg is just the seventh woman sculpted in the staircase, joining the likes of Susan B. Anthony and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

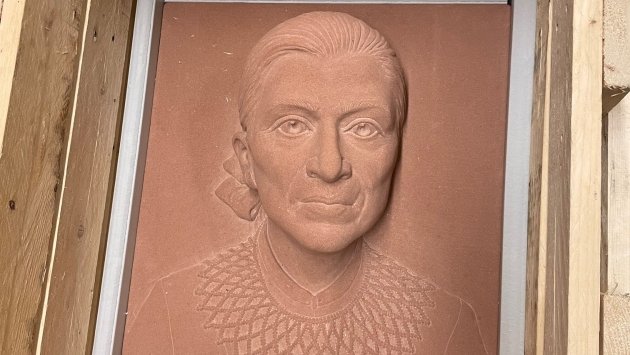

The sculpture was originally crafted in clay and made into a plaster cast by Meredith Bergmann, the same artist behind the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument in Central Park. From there, it was translated into stone by a Vermont stone carver named Evan Morse using a system known as “pointing” to ensure it was faithful to the original. Organizers installed it in the Capitol in June.

Bergmann had sculpted Ginsburg’s likeness in the past. A copy of her 2013 bust of Ginsburg, based on two days of observing the Supreme Court justice in her office, now belongs to the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

That piece depicted Ginsburg in her later years. The new sculpture took a different approach.

"This portrait is more like the emblem of Ruth Bader Ginsburg,” Bergmann said. “She’s younger. She's in middle age. It's kind of how she is remembered."

The wheels were put in motion for the project in 2020 under then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s administration, though Hochul since then fully embraced the enterprise. Bergmann and the state worked with the Ginsburg family to decide on some of the details — which collar she would wear, which glasses would adorn her face.

"When anyone conjures up an image of my grandmother in their mind, they think of glasses,” said Clara Spera, an attorney who is Ginsburg’s granddaughter. "But there was internal debate among the family and discussions with the governor's office and the artist about what style of glasses would be most appropriate for the sculpture."

They settled on the larger, round glasses Ginsburg wore in her early years on the court — which will be cast in bronze and painted to match the sandstone before being added to the sculpture in the coming weeks.

Over a couple weekends in late June and early July, Heller got to work on the inscription.

By then, he had worked with Bergmann, Hochul’s administration and the Ginsburg family to plan it out, coming up with a modern, hand-drawn Sans Serif font to spell out her full name and title.

Heller put on a respirator mask, took out a protractor and checked his angles. He then grabbed a newish three-eighths-inch chisel. “We’re in a new relationship,” he said of the tool — and sunk it into the letter “C,” which he had already mapped out on the wall. He hit the end with a mallet, and tink-tink-tinked away.

“This is just gorgeous material,” Heller said of the stone. “It's been a delight to work with. It's very refined, carves really well, as evidenced by this building. There's just amazing, intricate, exuberant carving everywhere.”

The Million Dollar Staircase — a nod to its original budgeted cost — is officially known as the Great Western Staircase, which was crafted over two decades in the mid-to-late 19th Century.

It has 400 steps that twist and turn up the first four floors of the Capitol. Bergmann likened it to an M.C. Escher painting. The first time she visited, it gave her vertigo.

At times, it seems like every inch is carved with something — flora and fauna here, famous busts there and mythical creatures in between.

“There's something near where Ginsburg will go that might be a mink,” Bergmann said. “We're debating that. We don't know exactly what it is, but it's a long, skinny animal that is not a squirrel.”

Ginsburg is just the seventh woman sculpted in the staircase, joining the likes of Susan B. Anthony and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The first six were something of an afterthought, according to Bevin Collins, who herself is the first woman to hold the title of Capitol architect.

“When the stair first opened, there was criticism in the papers because there were no women,” Collins said. “And so six women were hastily added."

The sculptures still leave plenty to be desired in terms of diversity. There’s only one known Black person among them — abolitionist Frederick Douglass, whose name was misspelled until the state added a second “s” four years ago.

Hochul’s administration may make more changes in the coming years. Jeanette Moy, the commissioner of the state Office of General Services, which oversees the Capitol, suggested there could be more additions to the staircase to come, though she acknowledged the selection process won’t be easy.

“I suspect there'll be a lot of conversations around that,” Moy said. “But I'm looking forward to it, and I hope we'll be able to do more of these projects.”

The unveiling of Ginsburg’s sculpture will occur once the glasses are added and the mortar is colored the same reddish-brown as the stone. Until then, it’ll remain covered from public view.

This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Jeanette Moy.

A new sculpture at Brooklyn Bridge Park evokes colonization and migration with weathered steel Harlem shake-up: How a Council upset returned Keith Wright from ‘the wilderness’