Rutgers Confronts Its History of Slavery, With Mixed Results

Nov. 25, 2021, 5:01 a.m.

Even though the university undertook an effort to understand its history, it hasn't continued to consistently share the learnings with students.

Rutgers University officials were deep into preparations for a year-long celebration of the institution's 250th anniversary in 2016, when students recognized a major part of the story behind its founding was missing.

"It did not include an acknowledgement of the history of slavery," said Marisa Fuentes, an associate professor in the Department of History at the New Brunswick campus.

"At that time the university administration did not know the history, other than it was the anniversary of its founding, and a few of the trustees’ names."

At the students' insistence, university officials conceded—with then chancellor Richard L. Edwards acknowledging complaints that the university had ignored its past, "such as that our campus is built on land taken from the Lenni-Lenape, and that a number of our founders and early benefactors were slave holders."

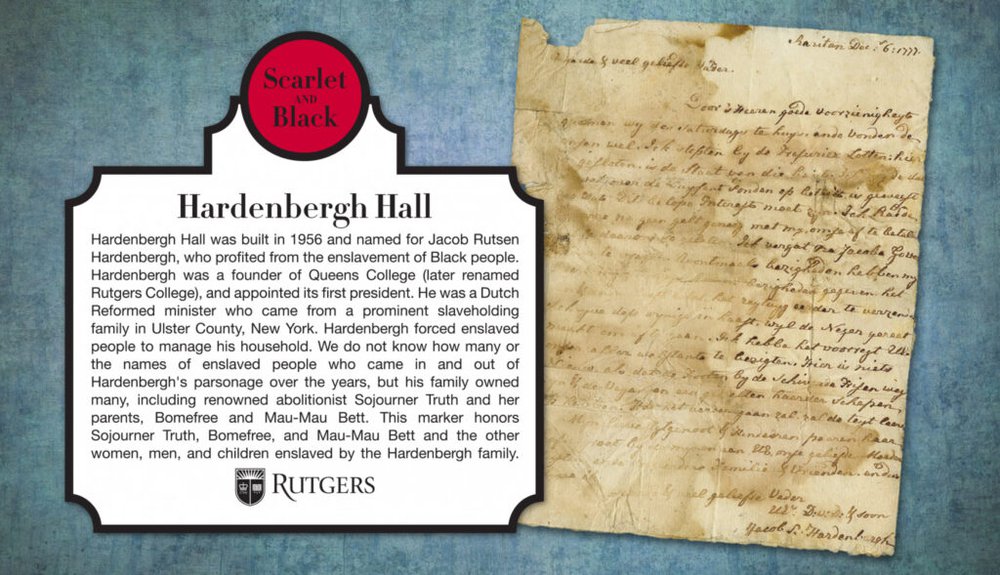

He launched the Committee on Enslaved and Disenfranchised Populations in Rutgers History in 2015, and out of that came the Scarlet and Black Project, an exploration of the experiences of Blacks and Native Americans at New Jersey's largest university.

The project yielded a rich trove of research and stories, including “Scarlet and Black: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History," a volume edited and written by Rutgers scholars. The first of three historical volumes, it takes an unsparing look at how the university’s colonial-era founders and the institution itself benefited from the slave economy, and the central role that enslaved men and women played in the construction of what was then known as Queens College. Rutgers was founded in 1766.

But, just five years after the debut of the Scarlet and Black Project—a reference to the university’s colors as well as the African Americans directly impacted by the history—many Rutgers students are unaware of the work, or their school's history.

Sara Oscilowski, a third-year student, was with a friend in front of the Sojourner Truth Apartments, an attractive 14-story dorm named after the legendary abolitionist and women’s rights activist. It was the in-depth work of the Scarlet and Black project that revealed Truth had been enslaved during her childhood by the family of Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh, the first president of Rutgers. The dorm was named after her in 2016.

“I had no idea about the apartments,” Oscilowski told WNYC/Gothamist. “I’ve never heard any professor, anyone write about it, I’ve never seen any post or anything, anywhere.”

Anusha Shanabag, a senior, said that despite living at the dorm she was also unaware and noted the lack of signage about Truth either inside or outside the building.

“There’s no information about her at all,” said Shanabag. “And in fact, people don’t even say ‘Sojourner Truth’. We call it the Yard. Or we shorten it to ‘SoTru.’”

In addition to the three historical texts, there were campus tours led by students as well as historical markers. The project helped “showcase the power of student activism,” said Fuentes, who is co-editor with historian Deborah Gray White of the first Scarlet and Black volume.

“There were also courses in the history department in particular that took the material and used it to introduce students to historical methodology and the archives on campus,” said Fuentes. “So early on there was more work done with undergrads specifically.”

But those students have since graduated, she noted, and the pandemic impacted the university’s ability to conduct public outreach.

Alexander Rosado-Torres, a graduate of Rutgers, once served as a Scarlet & Black tour guide. He remembered the feeling of standing on Will’s Way, a walkway named after an enslaved man whose unpaid labor helped build the campus. The experience, he said, was transformative.

“I was like, ‘Wow, Will, right?’”

Rosado-Torres is now a doctoral student at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, focusing on the history of education. He said his own research is uncovering the experiences of LGBT teachers, during the 60s and 70s in the United States, specifically in New Jersey.

"I’d say it was really in large part because of my own experiences in Scarlet and Black and being able to do that work," he said.

But he said there was a subsequent “falloff” in public engagement after the first few years.

Darrick Hamilton, director of the Institute for the Study of Race, Stratification and Political Economy at The New School, said institutions like Rutgers need to be intentional if they want to actually reach students.

“Knowledge is a necessary ingredient, but it’s not sufficient,” he said. “We also need a concerted strategy to actualize that knowledge and disseminate that knowledge through public engagement.”

Rutgers is one of a growing number of colleges and universities in the U.S. confronting their early history, and in some cases making amends. Students at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., agreed to tax themselves $27.20 each semester in order to pay reparations to the descendants of enslaved people from whom the institution profited.

Students at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island are making similar efforts in the wake of a report in 2006 documenting how the university’s founders played an active role in the transatlantic slave trade.

Student ImaniNia Burton heads the United Black Council at Rutgers, an umbrella organization for Black student groups. She said elevating the facts about the university’s founders and “acknowledging the fault is awesome,” but like the students at Georgetown and Brown, wants to see the administration do more, like provide more funding for Black students and foster a more supportive environment for them.

The impact of the Scarlet and Black Project is not lost on Jonathan Holloway, a historian and the first Black president in the university’s history. He joined the university in the wake of the protests after George Floyd was killed and presides at a challenging time, when conservatives nationwide are suppressing efforts to teach American history under the pretext of fighting critical race theory.

“We have legislatures who are now trying to make it illegal—and this is a long history behind this thing—to teach certain aspects of our country’s past," Holloway told Gothamist, "literally making it illegal to teach enslavement as part of our country’s past.”

Holloway said this makes it especially important for the university to tell history, starting with its own.

“We haven't even begun and when I hear about people not knowing who Sojourner Truth is, it affirms that work is ongoing.”