Rooftop gardens pitched for bus stops as cheap remedy to NYC’s flood problems

May 5, 2023, 5:01 a.m.

New York City's bus shelters cover four football fields of land. A Pratt Institute grad is pitching the city to turn the stops into garden-filled sponges.

Green roofs aim to attract pollinators and filter dust particles at bus stops in Utrecht, Netherlands. A Pratt Institute grad is pitching a similar idea to NYC's Department of Transportation.

As New York City spends billions of dollars preparing for its next extreme flood, new research suggests a cheaper, greener resource may already be scattered across the five boroughs: bus stop shelters. The concept would transform all the roofs of bus stops into urban gardens to sop up rainwater.

Ben Matusow, an urban planner, developed the idea as part of his master’s at the Pratt Institute’s Center for Planning and the Environment. He pitched it to the city’s Department of Transportation (DOT) last spring, given the agency’s bus stop shelter contract is up for renewal. The idea comes also with the opportunity to enshrine new greenery, which could help absorb carbon emissions and aid urban life.

Taken together, NYC’s bus shelters cover an area the size of four football fields. That means in an average year, they protect New Yorkers’ heads from over 6.5 million gallons of rainwater, which flows off the shelters onto sidewalks and into sewers.

Matusow’s idea centers around how much water small urban gardens (or green roofs) might be able to absorb if installed on each shelter. By his math, green roofs are less expensive than the city’s existing adaptation plans for extreme rainfall and better for the environment.

“The most important thing I found is there are opportunities everywhere to improve the sustainability of the city and the world,” said Matusow, who graduated in 2022 and started a new gig at DOT last month. “Basically, whenever you look into any city agency project there’s always an opportunity to make it greener.”

His analysis centered around how NYC is already committing billions of dollars to flood prevention, comparing the cost of those measures with the rollout of green bus shelters in other cities, both in the U.S. and abroad. Boston, Philadelphia and Buffalo are among seven American cities to have trialed green-roofed shelters, along with cities in countries from Brazil and Japan, to Amsterdam.

Green shelters would only be cost-effective at scale. When one bespoke green shelter was trialed in Pittsburgh it cost $12,000, according to Roofmeadow, the company who designed and installed it. In Utrecht, the Netherlands, each one of over 300 government-contracted green shelters cost the equivalent of $1,400.

Dividing the cost of current NYC flood infrastructure by the amount of water it captures means the number to beat, per shelter, is over $4,000. The city is home to approximately 3,100 bus shelters.

Here’s another way to look at it. Matusow’s analysis shows that bioswales cost $87 per gallon of water they can capture. If NYC’s green shelters cost as much as Utrect’s, they’d be more than twice as cost-effective per gallon.

Since Hurricane Ida unleashed record-breaking rain on the city in 2021, the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has spent billions of dollars on rain gardens, bioswales, and storage tanks to capture rainwater before it can overwhelm the city’s sewer system. The most recent “suite of stormwater infrastructure initiatives,” announced in September, totaled over $2.5 billion in ongoing and future plans.

The DOT’s new contract, beginning in 2026, will ask for the construction of hundreds more shelters across the city. By writing green roofs into their Request for Proposals, Matusow hopes that the initiative will be mandated for new shelters, and eventually that existing shelters may also be retrofitted.

If this plan is accepted, what are the benefits?

Greening a shelter is as simple as installing a tray of soil or rolling seeded matts over its roof. It’s more difficult ensuring each shelter can support the weight, and maintaining plants which might need watering or weeding.

For those reasons greening bus stops has had mixed success. On the East Coast, only one program — in the small, upstate town of Malone — survived more than a few years before being decommissioned for lack of funding. In San Francisco, a 2016 law made green roofing at least 15% of new constructions mandatory. In Utrecht, the Netherlands, home to the largest program in the world, a municipal contract mandated shelter green roofs in 2019.

Outside experts said the benefits could extend beyond flood control, as even small patches of greenery can play a surprisingly large role in cleaning the city’s air. Dr. Dandan Wei is an atmospheric scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory where she specializes in the city’s day-to-day carbon fluxes. Late last year her team used satellite images and carbon dioxide (CO2) absorption modeling to show the city’s trees and grasses already counteract all the emissions of on-road traffic on a sunny afternoon.

For NYC bus stops, Matusow suggests planting woodland or three-leaved stonecrop (Sedum ternaturm) — a small, durable succulent native to New York — onto the shelters because it casts shallow roots and doesn’t need any upkeep. Utrecht and Malone used it for the same reasons.

The most commonly used CO2 absorption model doesn’t include Sedum species, but using grass as a proxy. Wei calculated that greening the city’s bus extant shelters could absorb almost 100 kilograms of CO2 in a single hour of warm, sunny weather. That’s the equivalent of almost 250 miles’ driving in a typical passenger car or burning 11 gallons of gas, according to EPA estimates.

Quantifying the ecological benefits is hard for urban green spaces, according to Shino Tanikawa, executive director of the environmental advocacy group NYC Soil & Water Conservation District.

“We've been talking a lot about creating connectivity and habitat corridors, where organisms can actually migrate along these corridors,” said Tanikawa, who’s spent over two decades proselytizing for green roofs.

While Tanikawa doubts the power of individual shelter gardens to protect urban wildlife, the possibility of linking small green spaces together is enticing.

“I love it,” she said. “Bus stops combined with rain gardens that might be in proximity to [parks]. That might actually become a beneficial combination.”

To Matusow, all of these benefits speak for themselves. Putting a price tag them is just a necessary step to persuade policymakers, which he hopes will pay off. “I proved it can be done,” said Matusow. “There’s other places that do it. It’s just a matter of if they want to.”

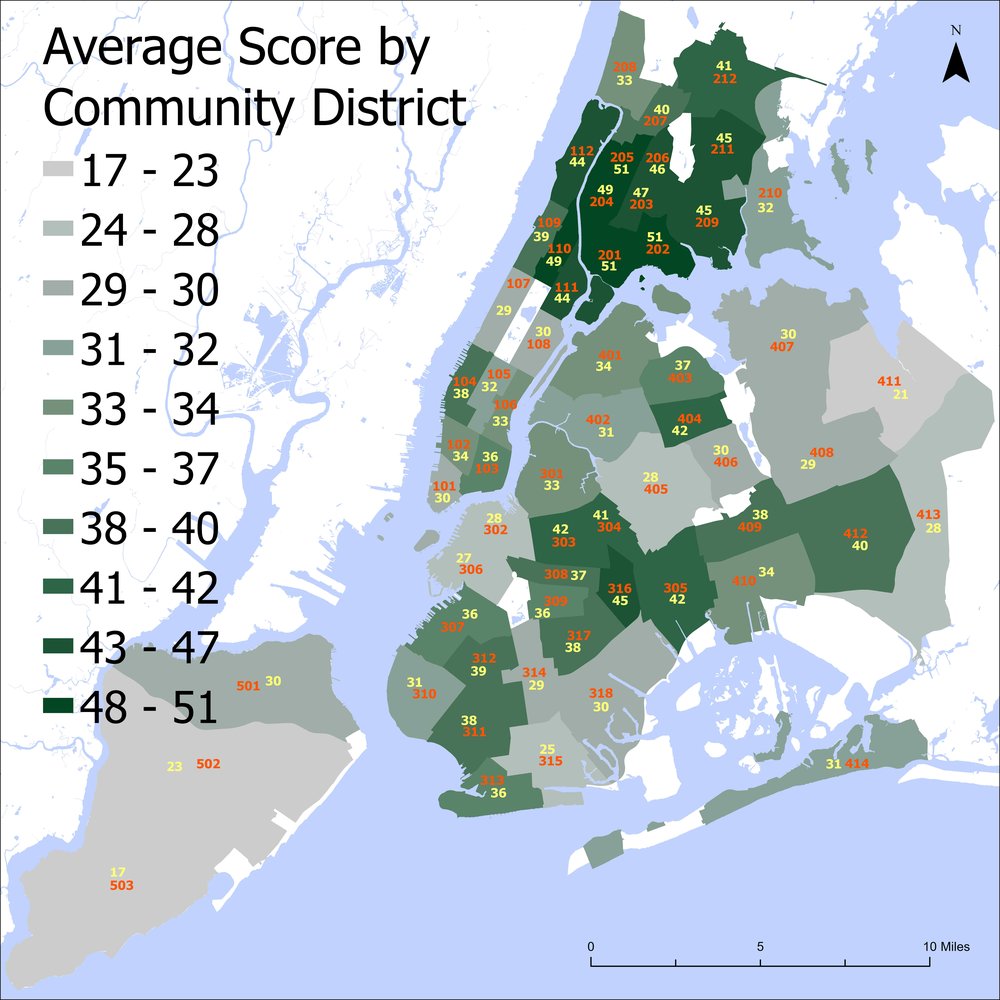

NYC’s current bus stop contract expires in 2026 and the process of finding the next contractor began in 2021. DOT states that its new contract will focus on constructing new shelters in underserved areas. According to Matusow’s research, the same parts of the city underserved by public transport — Harlem, Washington and Jackson Heights, and the Bronx — are also some of the most vulnerable to flooding. He said the bus shelter roofs could also be equipped with solar panels to create charging stations, though that’d make the endeavor more expensive.

Matusow presented the research to Michelle Craven, assistant commissioner of the DOT’s team overseeing the contract when work renewing it began in 2021. For legal reasons the DOT would not comment on the state of the “procurement process,” other than to say “we’re making progress.”

New Yorkers call on Gov. Hochul to stop radioactive water dumping in Hudson River NYC’s air is ‘as clean as it’s ever been,’ but that’s still pretty gross