NYC’s cooling centers remain closed despite spike in heat-related emergency room visits

July 19, 2023, 9 a.m.

The first two weeks of July witnessed about 150 heat-related emergency room visits — or seven times what happened over the end of June.

New York City is in its hottest stretch of the year — with max daily temperatures since the start of July averaging around 90 degrees Fahrenheit. This hot spell is not only uncomfortable, it’s also harming people.

Over this two-week period, the city's health department recorded nearly 150 heat-related emergency room visits, while only 20 were witnessed during the same timeframe at the end of June.

Despite these trends and as summer’s midpoint approaches, city officials have not opened municipal cooling centers, a network of more than 500 sites scattered across the five boroughs. Activating these air-conditioned facilities is part of NYC’s legally mandated plan for dealing with heat waves — but this public health lever comes with a rule.

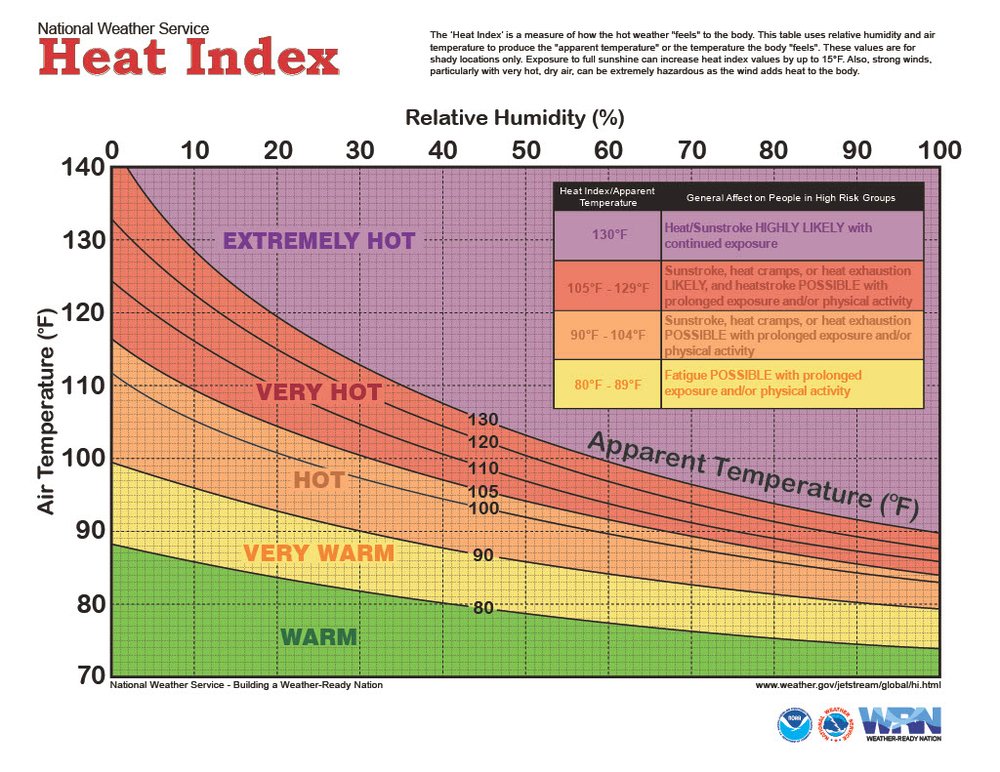

The city does not open cooling centers until the National Weather Service issues a heat advisory, and that doesn’t happen until the forecasted heat index reaches 95 to 99 degrees Fahrenheit for at least two consecutive days or any single day of 100 degrees or more. The National Weather Service told Gothamist that some parts of the city came very close to this mark this week, but the pattern was neither widespread nor prolonged enough to justify an advisory.

But health experts told Gothamist that while this threshold might be a good guideline for healthy people with working air conditioners, the conditions could already be too hot for residents who are more susceptible to the heat, such as older adults, people who are homeless or workers engaging in outside activities.

Sports studies and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration state that heat-related illness can occur at temperatures as low as 65 degrees Fahrenheit when a person is heavily exerting themselves and during high humidity.

“One of the important things when we talk about heat exposure is the environment,” said Dr. Uwe Reischl, a public health professor at Boise State University. “Heat stress is the result of a combination of air temperature and then humidity and the heat radiation coming from the sun — and air velocity, wind… All these four components contribute to potential heat stress.”

If it’s hot and dry, the body can cool off, Reischl added, but in New York City’s high humidity, that’s a very difficult function for the body to perform. Other factors that can accelerate the body toward heat stress include the type of clothing someone is wearing, the activity they are performing, their hydration, and air flow, Reischl said. Even healthy people can suffer from heat exhaustion, especially if they lack the resources or don't take precautions to stay cool.

When asked why the city had not opened cooling centers, the mayor’s office said it was waiting for the National Weather Service to issue a heat advisory before activating the cold shelter system. The National Weather Service said its decision to release a heat advisory is based on the heat index — a measurement that factors humidity and air temperature to gauge how the heat feels to a person — as well as emergency room admissions and heat deaths.

While this month’s slate of heat-related hospital emergencies is elevated, it is below the worst extremes witnessed in recent years. Those stretches tend to yield about 30 to 50 heat-related emergency room visits per day, though one weekend in July 2019 recorded more than 200.

But it’s the preceding purgatory — a place that’s not quite hell but still very hot — where at-risk groups can struggle.

The advocacy group Coalition for the Homeless said city agencies should make more cooling centers available and lower the threshold for when they are available. New Yorkers without housing have a mortality rate that is 50% higher than citywide averages, and as Gothamist recently reported, annual heat-related deaths have climbed in the city over the past decade.

“Imagine what it’s like for somebody that has no ability 24 hours a day to get in some place cool,” said David Giffen, executive director for the Coalition for the Homeless. “It’s extremely dangerous for those people [unhoused] to be exposed to extreme heat – there needs to be far more access to cooling centers.”

What heat does to the body

When your body gets hot, its automatic cooling system — sweat — kicks in.

“If the body is able to sweat appropriately and the sweat can evaporate from the skin, generally there's no problem related to heat stress,” Reischl said.

On a typical summer day in New York City, the humidity can reach well over 70% — at that point, the air is reaching its maximum capacity for holding water vapor. These conditions make it very hard for sweat to dry so the body can cool itself.

If sweat is unable to evaporate, the body can’t cool down, and heat stress becomes likely. A person starts feeling discomfort or overheated.

“Feeling hot is a key indicator of heat stress,” Reischl said. If left unmanaged, these symptoms may progress to dizziness and nausea. When it gets hot outside, Giffen said many unhoused New Yorkers show immediate signs of heat stress.

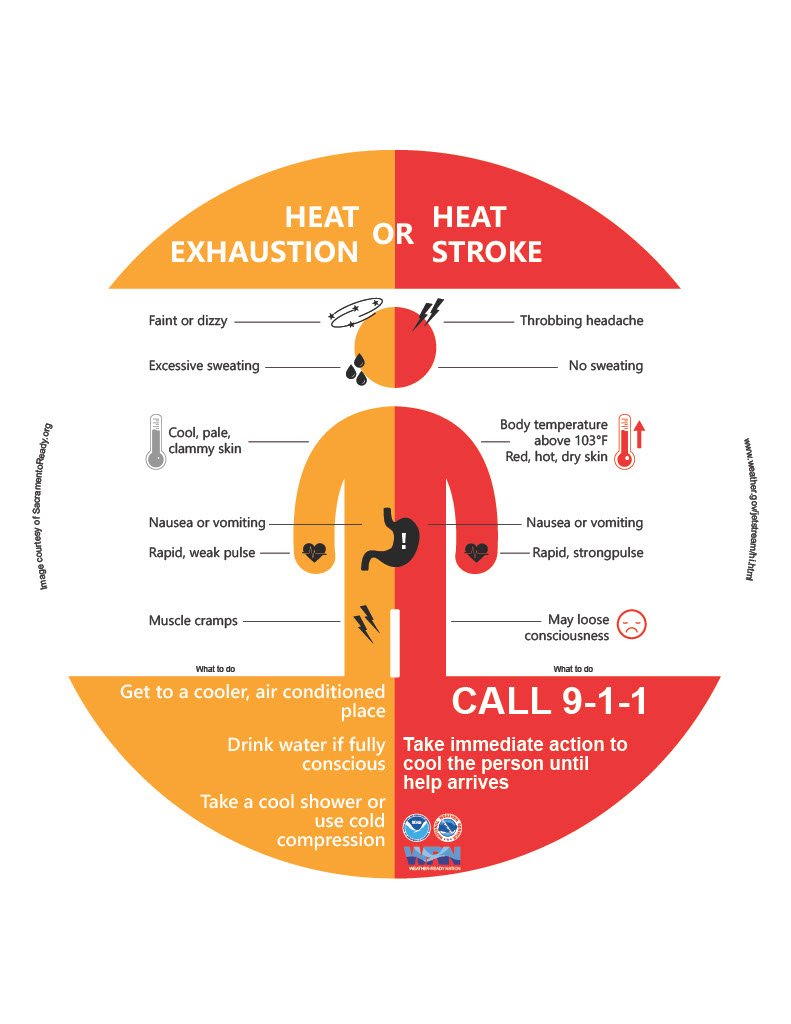

“Depending on how high the heat stress goes, they may actually faint, and that’s called heat exhaustion,” Reischl said.

The brain is the body part most vulnerable to heat. When temperatures rise too high, the body does whatever it can to keep the brain cool. It will produce as much sweat as possible and reroute the blood allocated for the internal organs to the skin in an effort to stay cool. If the body can’t find relief, the brain will overheat.

“When you have heat exhaustion, you have so much blood moving to your skin area that the amount of blood going through your brain is being reduced,” Reischl said. “This is why people faint when they experience heat exhaustion.”

This chart shows the symptoms of heat exhaustion versus heat stroke.

Determining how hot is too hot is not a one-size-fits-all number. But as the body ages, it loses the ability to adequately judge the heat.

If the humidity is low, and an individual isn’t working hard and wearing comfortable, loose-fitting clothes, then Reischl estimates that a person under those conditions would likely experience heat stress when temperatures are in a range of 85 to 95 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Traditionally, children, babies, elderly and people with chronic health conditions are the most vulnerable to heat,” Reischl said. “If you think about trying to accommodate these people, you have to set some standard, and 95 is very high.”

For those working out in the heat, such as construction workers, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration sets a much lower threshold temperature, at 82 degrees for outdoor laborers.

When it gets hot, employers are required to take precautions against potential heat stress. This includes liberal rest periods, providing water and shade. If it's strenuous labor, such as farm work, OSHA’s threshold drops to 73 degrees.

These factors are compounded by the materials and design of urban areas, like concrete and asphalt, which creates a “heat island” effect in New York City, making it over 37 degrees hotter than surrounding areas.

The hot spots exist in areas that lack greenspace, which are most likely low-income neighborhoods, where residents are less likely to have air conditioners or cool shady outdoor areas.

How to beat the heat

In a city of about 8.5 million people, more than 500 cooling centers serve about 16,000 residents each. These facilities are also limited by their own hours of operation, and some may not even be functioning. During last year’s Fourth of July heat wave, the comptroller’s office found that at least half of the cooling shelters were closed.

Gothamist strolled around the city last week, when temperatures were as high as 96 degrees Fahrenheit for non-consecutive days, to see how New Yorkers were coping with the heat. Many recounted creative techniques for keeping cool — from taking a very slow shopping trip at the market to sticking your head in the freezer periodically while living in your bathing suit.

“Keep your curtains closed. Wear minimal clothing. Take a five-minute cold shower every few hours,” said Brian Russ, a Brooklyn musician and teacher. “Walk deep into Prospect Park, as far away from the concrete of the city, and sit under a shady grove of trees for a few hours.”

For cooling off at home, Melanie Milano, also from Brooklyn, swore by her ice roller, a handheld device commonly used to reduce puffiness.

“When I was younger and poorer and had no AC, I used to freeze wash clothes and put them on my forehead,” Milano said. But she currently has an air conditioner.

Access to air conditioners is the most straightforward method for individual coolness, but such devices can be out of reach for people. In low-income NYC communities, 76% of households have a working air conditioner — a rate that’s well below the citywide average of 90%.

In a government-led investigation of heat stress deaths in New York City over the last decade, 71% died in their homes, and none of the deceased had a working air conditioner. City officials published a study this year showing that a program to give out free air conditioners in public housing staved off heat illness for older adults. (The New York City Housing Authority is reportedly threatening to evict the recipients in this program who aren’t paying their monthly utility fees).

In the absence of air conditioning, Reischl's advised drinking plenty of water on a hot day, but also recommended blocking out the sun's rays with loose clothing that covers the body, a hat or even an umbrella.