NYC taxpayers have paid a federal monitor $18 million to help fix Rikers. What went wrong?

Nov. 17, 2022, 5 a.m.

Thursday, attorneys for Rikers detainees are expected to ask for a federal receiver, who could override local laws and wrest control of the jails away from the city.

More than a decade ago, correction officers at Rikers Island beat detainees so severely that they broke their bones, perforated their eardrums, injured their spines, and punctured their lungs, according to a lawsuit filed at the time. Detainees demanded the federal court’s “strong hand to finally put an end” to the abuse.

The detainees got what appeared to be dramatic action. In a landmark settlement four years later, New York City officials and federal prosecutors agreed to a range of reforms, including the appointment of a federal monitor to help improve officer training, strengthen policies, and make Rikers Island safer for detainees and staff.

“Through this agreement, we will remain vigilant in ensuring that reform at Rikers Island is enduring and enforceable,” Preet Bharara, then the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, said.

Over the last seven years, city taxpayers have spent more than $18 million on that federal monitor, Steve J. Martin, and his team, according to data obtained by Gothamist and not previously reported. Yet reform at Rikers was neither enduring nor enforceable, according to an analysis of public data and interviews with more than a dozen people currently and previously involved in the jails.

The city jails system is actually far deadlier and more dangerous than it was in the fiscal year before Martin arrived: The rate of fights and assaults per detainee has nearly doubled, according to annual reports from the mayor’s office. A person in custody is seven times more likely to be seriously injured by another detainee. Staff are almost twice as likely to be assaulted. And slashings and stabbings have increased each of the last four years.

Eighteen people have died in city custody, or shortly after being released, so far this year — the highest death rate in more than a decade.

Thursday, the legal team that filed the original Nunez v. New York City class-action suit on behalf of Rikers detainees will return to the courtroom to argue that the monitor alone can’t fix this harrowing, entrenched problem. According to court filings this week, the attorneys will argue for the appointment of someone more powerful than the monitor — and even more powerful than the mayor. They are seeking a federal receiver who could wrest full control of the jails away from the city and override local laws that may inhibit progress.

Gothamist has reviewed the monitor’s seven-year tenure by analyzing public records and speaking to more than a dozen people on all sides of the city jail system — current and former correction officials, attorneys, advocates, and incarcerated people.

The consensus is that while Martin successfully guided the department in revamping its training regiment, expanding the collection of accurate data on violence, relocating teenagers to safer facilities, and strengthening certain policies, he failed to reform any significant part of life at Rikers.

Martin did not return a request for comment. His deputy, Anna Friedberg, declined comment, citing a provision in the consent decree barring the monitoring team from talking with the media.

$18 million, and counting

The monitoring team, now made up of eight correction experts and attorneys, had collected $17,824,660 as of last week, according to the New York City Law Department. An attorney and jails expert who was a corrections officer in Texas 50 years ago, Martin has personally earned $2.2 million working part-time since July 2017 (city records do not break down payments in 2015 and 2016). Based on Martin’s rate of $350 per hour, he worked an average of 24 hours a week on the Rikers matter, earning more than $400,000 annually. That’s much higher than the mayor’s $258,000 salary.

Martin is listed in public records as living in Texas and Oklahoma during his tenure with the city. He occasionally flies into New York for meetings and inspections, with hotel and air travel paid by taxpayers.

The team operates through a corporation called Tillid. Its employees are led by the deputy monitor, Friedberg, a former defense attorney involved in the original Nunez litigation who earns $320 an hour. Additional “subject matter experts,” including one based in Wyoming, round out the team.

The $18 million cost doesn’t represent the total expense to taxpayers, though, since an entire unit within the city correction department, staffed in part by attorneys, was created to provide information to the monitor and ensure compliance with his mandates. Correction Commissioner Louis Molina previously ran the compliance unit created by the Nunez case.

“Does this cost the city a lot of money beyond just the monitor and this team's salary? The answer is yes,” Vinny Schiraldi, a city correction commissioner under Mayor Bill deBlasio, told Gothamist. “And it's not successful. It's not so bad if it costs money and it works. But so far, it doesn't.”

Even Martin’s recent reports to the federal judge on the case are pessimistic about his own chance of success. In nearly three dozen filings, most running hundreds of pages long, the monitoring team has provided a transparent look into the deteriorating conditions at Rikers that reveal the futility of its involvement to this point. One of the most recent, from several months ago, used a version of the word “dysfunction” 24 times.

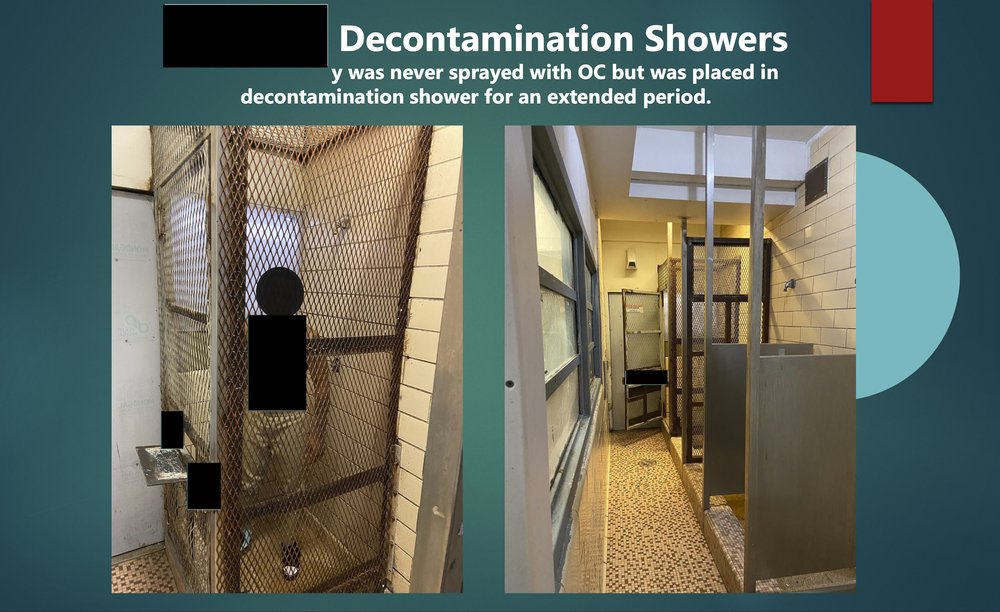

A “depth of dysfunction permeates the entire system,” and solving problems requires untangling a “quagmire of bureaucracy and dysfunctional practices,” the report said. It cited a recent “vivid example of staff dysfunction” — an incarcerated person was convulsing, but no correction officers provided medical aid, so detainees threw a trash can against a plexiglass window to get a guard’s attention; in response, officers sprayed everyone on the unit with a chemical agent.

Martin’s powers are limited: He makes exhaustive policy recommendations to jailhouse leaders, and reports compliance (or lack thereof) to a federal judge. But last month, the monitor argued in a report that neither he — nor, perhaps, the proposed federal receiver — could turn Rikers around: “The problems are so deeply entrenched and complicated that no single person, power, or authority will be able to fix them on the rapid schedule that the gravity of the problems demand.”

The monitor’s tenure is indefinite. He answers only to the U.S. District Court judge who has presided over the case from the beginning, Laura Taylor Swain. But the city is required to pay the costs of his oversight for as long as the monitor is in place.

How did we get here?

The 2011 Nunez case, filed by attorneys from the Legal Aid Society and two law firms, was buoyed after the federal investigation confirmed excessive force, a failure to protect detainees from violence, and the use of solitary confinement for teenagers accused of crimes. Bharara, then the U.S. attorney, said incarcerated teenagers were “consigned to a corrections crucible that seems more inspired by 'Lord of the Flies' than any legitimate philosophy of humane detention."

The resulting settlement, or consent decree, mandated that the department implement comprehensive guidelines on the use of force, including bans on hitting detainees on head or groin. Use of force to punish or discipline was no longer allowed. And all incidents had to be properly reported and investigated.

The decree mandated the installation of thousands of surveillance cameras, and the use of body-worn cameras by officers. It instructed the monitoring team to address violence at Rikers by helping the city correction department develop use-of-force policies, a staff recruitment program, and a system for tracking violent incidents. Martin and his team followed through on these elements of the consent decree, former and current officials said.

Officers are using force more than ever

Despite Martin’s actions, Rikers remains a jail complex where detainees say drugs and weapons are easily attainable. Overdoses and suicides are the leading causes of death, and staff call out sick at such high rates that posts are regularly left unmanned, according to the monitor.

Most detainees at Rikers have not been convicted of crimes; they’re held while awaiting court hearings.

In last month’s report, the monitor found that the correction department is in full compliance on just five of 25 suggested reforms. For example, the report credited the department with adopting a new use of force policy that the monitor had helped develop, but said the department was non-compliant on the mandate to actually implement that policy.

Indeed the monitor's primary mission, reducing use of force by officers, has measurably failed. Last year, the monthly rate of officers using force was three times higher than in 2016, according to the monitor. The number of incidents that lead to serious injuries has also skyrocketed during the monitor’s tenure — there were 353 through September of this year alone.

The explanation that the monitor gave for this violence is the same as it's always been: Failure to adhere to basic security protocols, like locking cell doors, and poor situational awareness, like failing to recognize escalating tensions.

The monitoring team also failed to bring change in its second area of focus, general violence. The number of slashings and stabbings went from 159 to 2016 to 420 last year, despite the fact that the detainee population was 50% lower.

Detainees interviewed said they hadn’t seen the federal monitor’s team visiting Rikers, but they had heard about him — and they doubted his effectiveness.

“A lot of people don’t care, because they feel like things aren’t going to change,” a detainee, Robert Cepeda, said in a phone call from Rikers. “The complacency in this place has been going on for so long.”

Ibrahim Ayu, who was released from Rikers in August, said he knows more about how Rikers works than any monitor living thousands of miles away who “comes with a big-ass report that nobody reads.” He said the monitor doesn’t understand the cruelty of day-to-life at Rikers, like how members of the Latin Kings gang once stole diabetes medication from the infirmary for him because staff wouldn’t take him for medical care.

Basic issues overlooked?

While the monitor failed to make the jail safer, its laser focus on that issue meant other problems which fed into the violence were left unaddressed, current and former correction officials said.

“Leadership was so concerned about getting compliance in those different categories, they totally ignored basic corrections,” John Gallagher, a former deputy warden at Rikers Island, said.

The department continues to fail to provide regular programs, recreation, and medical care to all detainees. Even getting people to court on time for their trials, a basic jail function, has gotten worse since the monitor was installed, according to the mayor’s management reports.

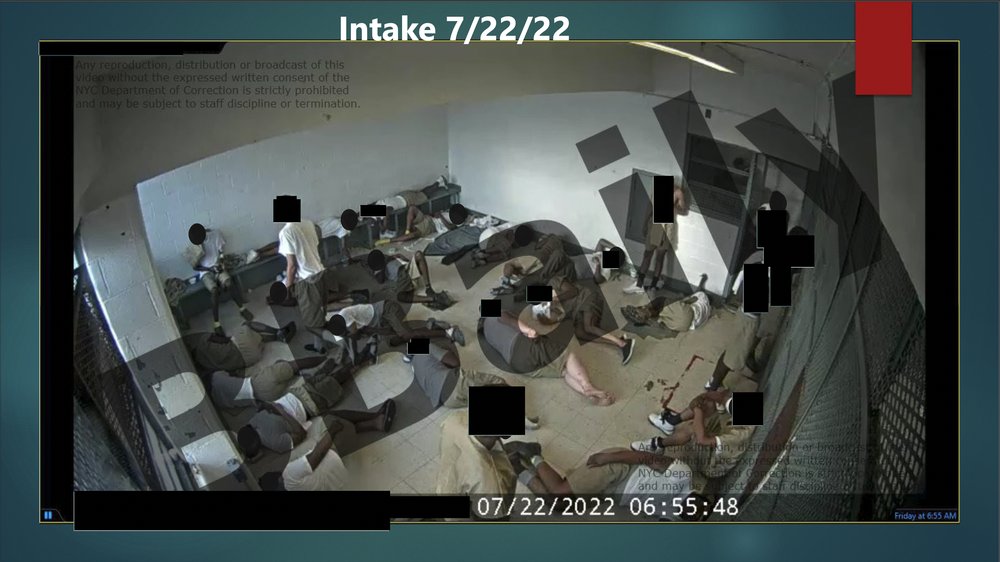

A major source of continued inhumane conditions is the Rikers intake area, where new arrivals are processed before being housed and where current detainees await transfer to another jail. Detainees’ accounts, along with photographic evidence obtained by Gothamist, indicate a lack of consistent access to toilets even as people stay there for more than 24 hours.

Critics on all sides

Advocates for the incarcerated view Martin suspiciously — not as an independent arbiter but as someone who is, at times, closely aligned with jail officials. Several people interviewed were confounded by Martin’s most recent report, in which he praised Molina and his senior staff for their professionalism and focus, while concurrently panning the way the jails operate: “Nearly every facet of the jails’ operations, procedures and practices needs to be dismantled and reconstituted.”

Victoria A. Phillips, a chaplain at the jails, has long followed the politics surrounding the monitorship. “If you’re getting paid multiple millions of dollars there is no excuse for you not to hold the people failing to do their job accountable,” she said. “In one sense you say Rikers is worse, but in the other sense you’re clearly saying my homeboy here needs a pass. … Steve Martin needs to be honest about that, or maybe he needs to be replaced.”

Molina’s predecessor as commissioner, Schiraldi, believes that the indicators used to measure success have gotten “mushier,” which “calls the legitimacy of the monitoring process into question.”

Seven years in, “it could be that, what reflects badly on the city, also reflects badly on the monitor,” Schiraldi said. “Admitting defeat in some respects might be problematic for [Martin]. He's also making a lot of money off of this, and I don't think he's any more prone to having his finances impact his recommendation — but you got to ask that question.”

The monitor’s term has outlasted one mayor and three correction commissioners. But unlike other correction officials, Martin does not do interviews or appear at city council hearings, which has helped to inoculate him from the local political brouhaha surrounding Rikers.

Still, his fingerprints are on much of what the correction department does. When the department loosened disciplinary policies last month, even for minor violations of use of force, the monitor endorsed the changes. And when the department put the kibosh on a long-developed plan to punish detainees who violate rules with a more humane system, it said it was acting on “directions” from the federal monitor.

The powerful correction unions, meanwhile, despise the monitor’s scathing depictions of the department, and allege that the monitoring team is biased because its finances are tied to there continuing to be a need for jail oversight. In its own report last year, the Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association alleged that “the monitor is stuck in a conflict of self-interest, incentivized to publish reports that portray no progress and dire conditions in NYC jails, while extending the trail of financial gain indefinitely with each negative report.”

It added: “A positive report would signal the end of the monitor’s financial gains from NYC taxpayers.”

What’s next?

A growing chorus of critics say the time has come for a judge to appoint a federal receiver, who would have the power to unilaterally implement changes. In a letter to the court filed this week, the attorneys in the Nunez case said they plan to seek a receivership because of rampant use of force, backlogs in staff discipline, and unsupervised jail units.

The first thing that critics hope a receiver can do is break union contracts that authorize, for example, unlimited sick leave, which are blamed for dangerous levels of absenteeism, unmanned posts, and a lack of officers to take detainees to medical care, recreation, and visits.

“Time's up,” Schiraldi said. “I think if we had a receiver for seven years, we might make much more progress than, you know, killing more trees with 300-page reports.”

Still, federal receivers are extraordinarily rare in U.S. history, and they represent the most dramatic measure that can be taken by the federal government against a jail other than forced closure.

A motion for a receiver could also trigger a prolonged legal battle. In a letter filed with the court, the city said it opposed a takeover. “There is nothing that a receiver would do that the Department and the City are not already doing,” wrote Kimberly M. Joyce, senior counsel for the city. “In this moment bold remedies are necessary, and this administration is ready, willing, and legally able to take such steps.”