NYC Health Experts Grade Mayor De Blasio’s COVID Legacy

Dec. 14, 2021, 4 p.m.

As part of our ongoing Grading de Blasio series, WNYC/Gothamist asked a panel of local health experts to look at how the mayor managed the calamity and what he leaves behind as New York City preps for future surges.

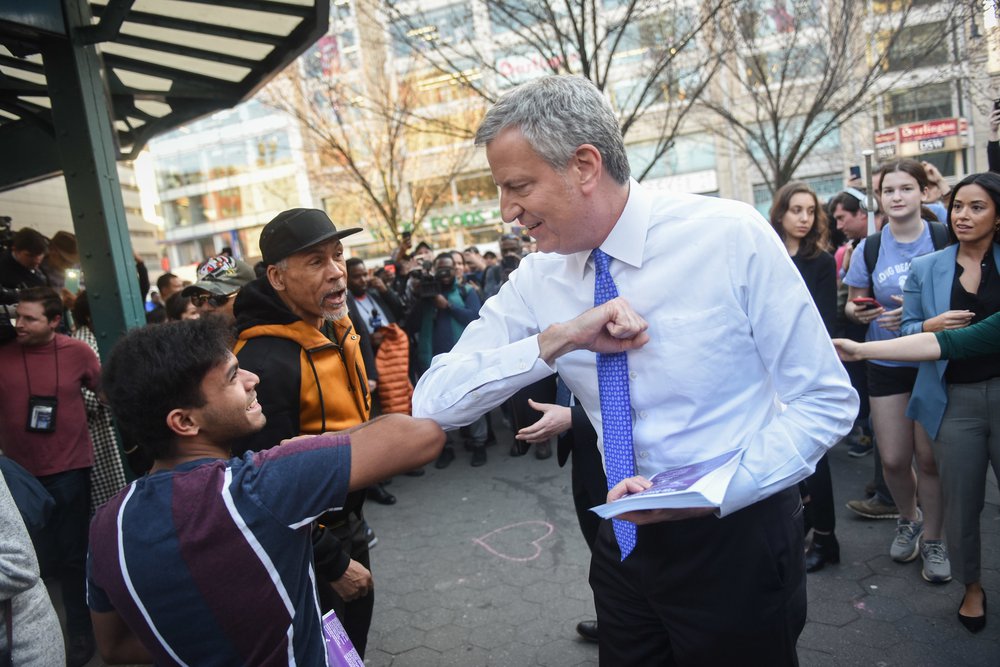

Mayor Bill de Blasio hands out fliers regarding COVID-19 preparedness in Union Square on March 9th, 2020.

Mayor Bill de Blasio has helmed the city through every twist of its pandemic journey.

New Yorkers lived through the city becoming the nation’s early epicenter in March and April 2020, as hospitals filled and the lockdown quieted the busiest streets in America. The Trump administration failed to deliver on basic resources such as COVID tests and personal protective equipment (PPE), causing the city and the state at large to struggle during the initial onset.

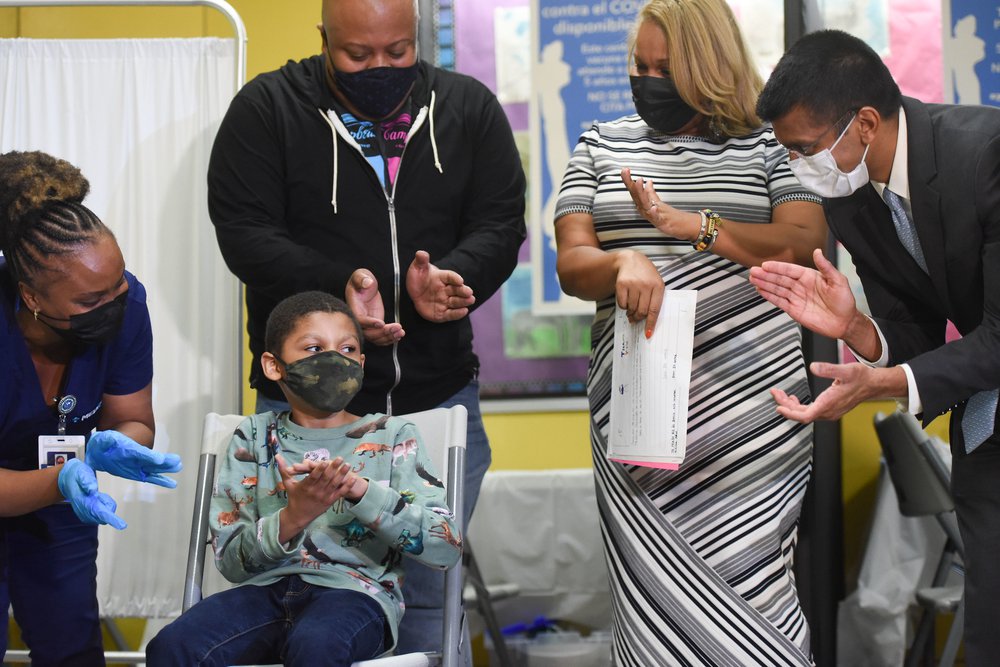

Tremendous progress has occurred since those early days, but the city’s battle continues. Health care workers learned how to fight the virus in frontline hospitals, while researchers developed emergency and preventative medicine at lightspeed. Exactly one year ago, Queens-based nurse Sandra Lindsay became the first American to take an authorized dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Soon after, New York City was hit with a huge winter wave and then the delta variant, which is currently surging again. Now, more than a dozen cases of the omicron variant have been reported in the boroughs, and the city's public health experts say they believe this mutant is circulating in the community.

As part of our ongoing Grading de Blasio series, WNYC/Gothamist asked a panel of local health experts to look at how the mayor managed these calamities and what legacy he leaves behind when it comes to the city’s COVID landscape. They gave mostly positive grades but said many lessons could still be learned when it comes to testing access, data transparency, vaccine delivery and coordinating with businesses.

Testing and Transparency

COVID tests were scarce in the early days of the pandemic. That short supply was compounded by other resource limitations: By late March 2020, New York City health officials instructed health care facilities to only test those who were hospitalized, citing a lack of PPE. When the first wave peaked a month later, fewer than 10,000 people per day were being tested on average, and a little more than half of those tests came back within 48 hours.

In May 2020, de Blasio announced the creation of the city’s Test + Trace Corps, a group of city workers who track down close contacts of COVID-positive people and encourage them to quarantine and get tested. The Corps worked to make testing more readily available in neighborhoods hit hard by the first wave of the pandemic, teaming up with community groups to place mobile units in highly trafficked areas. Its staff now includes about 2,000 contact tracers.

Over time, testing capacity increased: By early 2021, more than 69,000 people got tested daily on average, and turnaround times improved, with three-quarters of tests being returned within two days. To combat long lines that lasted for hours, the city opened dozens of new testing sites, including mobile units.

In the run-up to this winter holiday season, the mayor announced that the city would double its fleet of mobile testing units. But the Department of Education’s testing strategy for schools has prompted criticism from teachers, parents and public health experts, who say too few students are being tested to give the city an accurate picture of COVID transmission in the system.

“It’s been a learning curve for the city,” said Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, professor of epidemiology and medicine at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “To [the city’s] credit, they had to build this from nothing.”

The city’s COVID data infrastructure has also evolved over time. The first pandemic data dispatches were simple case counts, limited by the scarcity of testing.

After urging from experts and the public, de Blasio agreed to share data on COVID cases, hospitalizations and deaths among New Yorkers of different races and ethnicities. The numbers, first released in April 2020, show stark differences between groups: Black and Hispanic New Yorkers have been hospitalized with COVID at nearly twice the rate of their white neighbors, and they’ve borne the brunt of deaths from the virus.

As testing has improved, so has reporting. The city now posts daily or weekly updates on an array of COVID stats to its data dashboard, including vaccination rates and breakthrough cases. The numbers are also posted to GitHub for researchers and data enthusiasts to download and analyze. And de Blasio shares select indicators at his virtual press briefings.

“They had their dashboard up and running before most other places,” said Dr. Celine Gounder, an infectious disease specialist and epidemiologist at NYU and Bellevue Hospital who occasionally attends the mayor's briefings as a guest speaker. Gounder commended de Blasio on the briefings but said she’d prefer if they were led by public health officials.

“When you have a politician who’s leading the briefing, anyone who does not belong to his or her political party will automatically tune out everything they’re saying,” Gounder added.

El-Sadr praised the wealth of metrics shared and the city’s transparency improvements over time — but said more could be done to ensure that the data is accessible to everyone and not just the tech-savvy.

“You need to bring the findings back to the people” they’re about, El-Sadr said.

Hospitals, Nursing Homes And Oversight

Throughout the pandemic, hospitals and nursing homes have been a key battleground in the fight against COVID-19. In spring 2020, it was a huge challenge for these facilities to obtain enough N95 masks and other personal protective equipment for their workers. Ventilators and hospital beds also became in short supply in New York City.

Nursing homes and assisted living facilities often lack the proper infrastructure for infection control, even beyond the coronavirus pandemic, said Dr. Denis Nash, a professor of epidemiology at the CUNY School of Public Health. “Even before COVID, there were flu outbreaks all the time,” he said. “I think it's a general failure of our elected officials and our public health departments.”

De Blasio sought to leverage the city’s procurement power to assist with the supply shortages by signing an executive order that allowed agencies to contract with suppliers more quickly — without facing the typical oversight from the city comptroller. New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer sharply criticized the move and sued the city to regain oversight in July 2021, saying unsupervised spending led to massive procurement failures, including contracts with suppliers that never delivered.

Amid the chaos that characterized the initial worldwide scramble for protective gear, the de Blasio administration did distribute millions of masks, face shields, gowns and gloves to nursing homes and hospitals across the city and deployed additional clinical staff to help on the frontlines in spring 2020. The city also worked to build up a stockpile of nearly $1 billion of personal protective equipment in late 2020 to prepare for the second wave.

But Stringer slammed de Blasio for having to play catch-up in the first place because of insufficient pandemic preparedness. He issued a report this August noting, among other issues, that the city had allowed its stockpile of N95s to expire years earlier.

“When you don't have a plan, there are probably going to be lots of missteps,” said Nash. “Even when there is a plan, when you're dealing with a new pathogen you don't necessarily know exactly how it's going to behave or exactly how you can respond to it or what the most important issues are going to be very early on.”

Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo faced widespread criticism for releasing COVID patients directly from hospitals into nursing homes early in the pandemic. But de Blasio made a similar move when his administration opted in April 2020 to house COVID patients in hospital beds co-located with the Coler Rehabilitation and Nursing Care Center on Roosevelt Island, a city-run facility. The virus spread quickly through the center, and advocates said they were caught off-guard by the decision. Residents of the nursing home, many of whom have serious disabilities, later protested how they were treated.

Meanwhile, the makeshift field hospitals the city constructed to help alleviate overcrowding in traditional medical centers were often underutilized. The hospital at the U.S.T.A. Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, which cost the city $52 million, served 79 patients. Richard Mollot, executive director of the Long Term Care Community Coalition, which advocates on behalf of nursing home patients and their families, suggested the city should have taken advantage of those field hospitals to isolate people with COVID-19 who would otherwise be placed in nursing homes.

The Vaccine Rollout: Impressive With Room For Improvement

Despite the occasional fumble, public health experts agreed that the city did an impressive job with rolling out the COVID-19 vaccines — and the evidence is in the numbers. At 71% fully vaccinated, New York City has a higher vaccination rate than the national average — 61% — and is on par with most urban areas.

But they said there is also room for improvement. Many of the vaccine rollout’s flaws were the result of historical weaknesses in the public health systems such as pitfalls in messaging and outreach, said Dr. Susan Michaels-Strasser, an epidemiology professor at Columbia Mailman School of Public health. But the city also struggled to establish infrastructure for the giant campaign, especially around booking appointments.

As New Yorkers waited for vaccines to become available, the city missed an opportunity to open an early dialogue with marginalized communities and get ahead of the misinformation, the experts said. This delay in messaging doubled the efforts needed to communicate about the vaccines because the misinformation has to be disproven on top of disseminating the correct message. Dr. Ayman El-Mohandes, dean of CUNY Graduate School of Public Health, likened it to apples.

“I come to you and tell you, apples are good for you,” said El-Mohandes. “But if you already heard that apples are poisonous, then there is a hurdle to cross because you have received negative information, and your level of suspicion is higher, and my credibility is lowered. My job then is to prove to you that apples don’t kill you and also that they are good for you.”

And this is particularly dangerous, Michaels-Strasser said, because historically the most vulnerable communities are the most reluctant and distrustful of government and medical institutions. El-Mohandes said these communities should have been the target and emphasis of early information campaigns with the help of local leaders and community centers.

“It’s natural for people to be fearful in a time like this, and uncertain and to be questioning,” said Michaels-Strasser. “We have to be better at messaging what we know and what we don’t know so communities understand that we’re not perfect, but we are honest and that we are giving the information based on the best available.”

Similar trust gaps can also emerge among health workers, despite their science-based training, as WNYC/Gothamist reported this fall.

This trust could have been gained through early messaging made by people who sounded and looked like those most reluctant or marginalized. Many New Yorkers got sick or lost loved ones during the pandemic – this group understood the risks intimately. Their stories could have been a catalyst in changing minds, experts said.

For those least at risk of hospitalization or death from the coronavirus, getting a vaccine may not seem like an urgent matter, but it is for those around them. El-Mohandes said special messaging should have targeted this reluctant group in the beginning to explain that vaccination was a matter of their social responsibility and that the shots would also prevent them from infecting vulnerable loved ones.

Messaging was not the only problem, accessing appointments proved a serious barrier. It was a big mistake to rely on an online system for reserving a vaccine appointment, said Michaels-Strasser. First, it made it difficult for the elderly who don’t usually go online to secure medical visits. Second, the internet is not something that is equally available across society. Some of the hardest communities to reach are the least likely to have reliable access, said Michael-Strasser.

Even after securing an appointment, mass vaccination sites, which served their purpose well, can feel impersonal. Most people preferred going to their doctor’s office or local pharmacy to get their vaccine, according to a poll conducted by El-Mohandes. This was not a possibility until later into the pandemic due to the stringent storage and delivery protocol. If the vaccine could have been available locally by trusted medical professionals in the community, it would have allowed New Yorkers to get vaccines where they normally get them and where they can also speak to someone they trust about their reservations.

For New Yorkers who do not have access to a local doctor or pharmacy, community health vans are a way of bringing medical services like vaccines and educating the public. The presence of a mobile health clinic supplying food and PPE can be a way of rallying neighborhoods to get vaccinated. They are also convenient.

“You’re not asking people to come to you; You’re going to them with the service,” said Michaels-Strasser.

The mass vaccination sites had another big pitfall: waste. While some facilities ran out of the doses they needed, others had to throw out unused vials of the vaccine. This could have been resolved with better coordination between government and health providers as well as a system of communication between sites that would allow surplus to go to areas where demand was highest. Leftover vaccines could also be distributed to people on a standby list, allowing more people to be vaccinated.

The most important accomplishment in this pandemic is learning from it for the next time. At the end of 2020, the city announced the creation of the Pandemic Response Institute to prepare New York City for future public health emergencies. The city says its research and findings will be used in the future to track and monitor disease outbreaks and create community partnerships, especially with vulnerable and hard-to-reach groups.

How NYC Businesses Feel About The City’s Response

While business owners felt they could easily grasp vaccine and mask mandates as public health measures, some of the other required rules seemed to conflict and change so rapidly that staying compliant was difficult and created some financial hardship, especially for restaurants.

Susannah Koteen, owner of the Harlem restaurant Lido, said there were differences between state and local guidelines, and some did not make sense. For example, Koteen said that New York City restaurants remained closed or had limited capacity early in the pandemic while outside the city, restaurants were at full capacity, even when their infection and hospitalization rates were higher.

Not being fully opened meant restaurants needed every avenue available to stay afloat, including serving alcohol to go, said Jeremy Wladis, owner of Upper West Side restaurant Harvest Kitchen. When this was stopped in July and serving alcohol was curtailed by requiring food purchase, it put a large dent in his recovery.

Many restaurant owners said the constantly changing rules also resulted in a bevy of fines. Koteen, who spent about $40,000 on her outside dining structure, said restaurants were not provided with early guidance about the Open Restaurants Program, but then inspectors showed up requiring major and costly changes. Wladis said he felt fortunate to get only a fine of $1,500. Other restaurant owners confirmed that inspectors gave conflicting information, and fines could reach well into the thousands of dollars.

“We built and rebuilt our dining cabana three to four times,” said Wladis. “They’ve been knocked down and city regulations changed multiple times – the inspectors didn’t know what they were talking about.”

Restaurant owners were grateful for the Open Restaurants program and credited it with helping them stay afloat, but the outdoor dining spaces were also, at times, dangerous. Wladis said people have been hit exiting and entering them by motorized vehicles traveling in the bike lane, which is located between the street dining spaces and the sidewalk.

The city also created several programs to support restaurants financially during the pandemic, but programs quickly ran out of money because of the great need. Wladis felt the city could have done a better job in allocating aid – by having more funds available for restaurants struggling to stay open instead of providing relief for ones that were closed.

While restaurant owners have described the restrictions placed on them by the pandemic as “painful” and “excruciating,” they also said the city tried its best in a situation with so many unknowns and dangers. For the next public health crisis, they advised the city to consult them about logistics and what protocols make sense for operations. Many of these difficulties could have been avoided if the city got feedback on their plans, said Koteen, who also is a member of the NYC Hospitality Alliance.