'No Hispanics' or 'grandmotherly types': NY prosecutors face complaints over jury bias

March 21, 2023, 5:01 a.m.

Judges have already ruled that the prosecutors broke the law.

Ten current and former New York prosecutors who judges say illegally screened out potential jurors because of race or religion are facing ethics complaints that could prompt investigations or disciplinary actions.

Judges have already ruled either during trial or in appeals that all 10 prosecutors broke the law. But a group of law professors is now bringing ethics complaints against the prosecutors in the hopes of holding them accountable for what they did.

They have not yet faced any public discipline, according to state court records. Several of them were even promoted.

In some cases, the people who the prosecutors convicted filed appeals arguing that jury selection was biased and their convictions were overturned — but only after they had spent years behind bars.

The law professors are bringing the complaints, filed Monday with attorney grievance committees and shared first with Gothamist, as a way of finally holding the prosecutors accountable for violations that in some cases date back decades. The group, which calls itself Accountability NY, started submitting complaints against prosecutors accused of misconduct in 2021.

They said the violations are emblematic of a larger problem in the court system: attorneys illegally excluding jurors based on race and other aspects of their identity. Experts said it’s an illegal practice that undermines people's right to a fair trial — especially people of color.

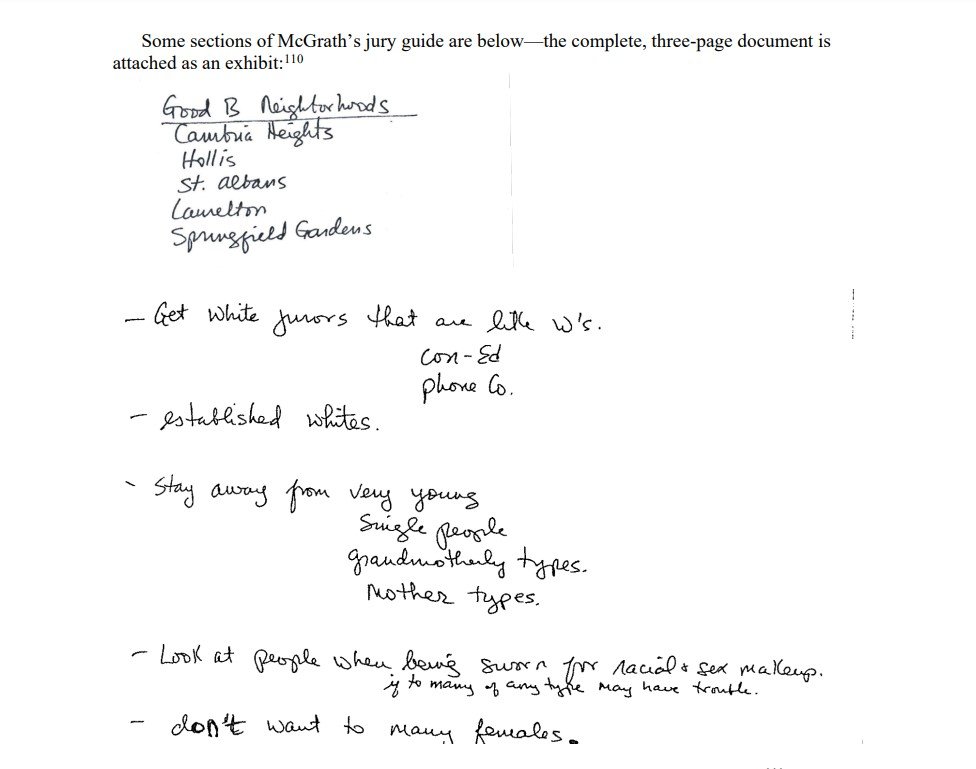

The complaints name prosecutors in five district attorneys’ offices, including Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens. In one 2018 case, a judge found that a prosecutor acted illegally when he struck all the Latino prospective jurors for a Latino man’s trial. In another that same year, a judge ruled that a prosecutor illegally removed the only two non-white people for the trial of an Afghan-American. In one case, a former prosecutor admitted to using notes filled with racist and sexist instructions — including “No Hispanics” and “Stay away from grandmotherly types” — to avoid choosing diverse juries in the 1990s.

“Diversity is an essential safeguard,” said Peter Santina, managing attorney of Civil Rights Corps’ Prosecutorial Accountability Project, which helped to file the complaints. “A representative jury can mean the difference between someone being wrongfully convicted or not.”

Prosecutorial discipline is sometimes meted out confidentially, so it’s unclear if any of the prosecutors has faced professional consequences that are not reflected in their public records.

When choosing jurors for a criminal trial, prosecutors and defense attorneys in New York are both allowed 10 to 20 peremptory challenges — or chances to dismiss a juror without providing a reason. But they aren’t allowed to dismiss a juror because of their race or religion, and if asked, they have to give a different reason for the dismissal. It’s up to a judge to decide if the reason is legitimate.

The reason for the rule is to prevent attorneys from shaping all-white or majority-white juries, which researchers have found engage in less rigorous deliberations, convict at higher rates and are more likely to sentence someone to death in capital cases.

Ron Wright, a professor at Wake Forest Law School and former prosecutor said race still plays a central role in jury selection, even decades after the U.S. Supreme Court made it illegal. He said both prosecutors and defense attorneys use race as a way to judge which prospective jurors are least likely to agree with their theory of the case.

“There are life experiences that make it easier or harder for a juror to see the case the way that that attorney wants them to see it,” he said.

Race, he added, “serves as a pretty good proxy for a lot of the life experiences that make someone more sympathetic to the prosecution or less sympathetic to the prosecution.”

Wright noted that prosecutors aren’t the only ones who choose jurors based on race – defense lawyers do it too. A 2018 article he co-authored found that North Carolina prosecutors remove about 21% of Black jurors and 10% of white jurors in criminal cases, while defense attorneys strike about 22% of white jurors and 10.5% of Black jurors.

“Those numbers tell me that some kind of racially influenced reasoning is happening,” Wright said. “But, you have to ask, well, was it the only reason? Was it one among four reasons?”

‘I wasn’t going to get a fair trial’

One of the grievances filed Monday centers on the case of Dexter Murray, who was on trial in 2018 for several crimes, including assaulting a police officer. Murray made the uncommon choice to represent himself in court, and during jury selection, he felt his chances of acquittal slipping away as he watched a Manhattan prosecutor striking one Black juror after the next .

“I was afraid at that point, because I knew I wasn't going to get a fair trial if you were getting rid of all of my peers,” he said in an interview.

Murray had previously served 21 years in prison for a crime he committed as a teenager, and he spent much of his sentence working in the law library, where he studied court cases in the hopes of building his own successful appeals.

When Murray noticed Assistant District Attorney Melanie Soberal had removed four out of five Black people from the jury, he knew the relevant Supreme Court case from memory.

“The prosecutor, Soberal, is excluding all the Blacks. I am an African American,” he told the judge, according to court transcripts.

Soberal offered explanations that she said were unrelated to race, and the trial judge allowed her to dismiss the prospective jurors. But in 2021, an appellate court sided with Murray. Justice Dianne Renwick ruled that Soberal had illegally struck at least one of the Black jurors because of his race and reversed Murray’s conviction and one-year jail sentence, which he had already served pre-trial.

Soberal could not be reached for comment. She left the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office in 2020, and DA Spokesman Doug Cohen said she was well-respected by the attorneys there during her tenure. Still, Cohen added, the office takes allegations of bias in jury selection seriously.

“A fair jury selection is essential for equal justice under the law," said Cohen, adding that the office conducts trainings on the subject on an ongoing basis.

Of the 10 ethics complaints filed this week, six are against current and former prosecutors in the Queens District Attorney’s Office.

One of those, dating back three decades, names Christopher McGrath, a former prosecutor who used notes during jury selection that outlined types of jurors to include or exclude based on their race, religion, gender and neighborhood, as well as certain personality traits. The notes, which McGrath admitted to using during at least two trials in the 1990s, say to “look at people when being sworn for racial and sex makeup.” They caution against choosing “Hispanics,” “grandmotherly types” and “Italians,” if the defendant is Italian. They also instruct prosecutors to pick “No one from Post Office. (Flaky).”

McGrath left the Queens District Attorney’s Office in 1997 and now serves as general counsel for the Police Benevolent Association, the NYPD’s largest police union. In 2020 and 2021, the courts tossed out three decades-old convictions from cases he prosecuted because of the notes. But even though McGrath’s conduct resulted in overturned convictions, he never faced public discipline, according to his state court record.

A spokesperson for Queens District Attorney declined comment.

"As there is litigation pending as to how this office is able to respond to complaints filed with the grievance committee, we are unable to comment at this time," the spokesperson said. McGrath and the PBA also not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Repercussions are rare

It’s rare for a judge to find that a prosecutor has illegally screened out jurors because of their race or religion.

The cases at the center of these 10 grievances are the uncommon exceptions, when a judge stated on the record that a prosecutor had broken the rules. It’s rarer still for prosecutors to face discipline. Between 2004 and 2008, New York trial and appellate courts ruled that prosecutors committed misconduct 151 times, but public sanctions were imposed in just three of those cases, one review found.

Wright at Wake Forest Law said it’s also unlikely for prosecutors to face internal discipline or career setbacks for discriminating against potential jurors.

“Most of the time, an employer would say, ‘Oh well, that was a borderline call and you stepped over the boundary, so watch out and don’t do that again,’” he said. “But then that’s kind of the end of it. It would have to be either repeated or really a blatant violation before I would expect to see any kind of negative job repercussions.”

Reforming the system

Bias in jury selection isn’t the only reason some juries are not as diverse as they could be. A report released last year found that 60% of people who show up for jury duty in Manhattan — not even accounting for those who are actually chosen — are white, compared to 46% of the Manhattan population.

The report recommended several steps to increase diversity in New York juries, such as raising juror pay. They also suggested stricter rules for jury selection, which would prohibit attorneys from removing someone if a “reasonable person” would believe that race played a role. That recommendation has not been adopted at this point.

The Office of Court Administration did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

New York is one of several states that has considered changes to its jury selection process, to prevent discrimination. A New York bill introduced in both chambers of the state legislature in 2021 would repeal the state law that allows attorneys to make peremptory challenges, but the measure has not made it out of committee.

Arizona passed a bill in 2021 that got rid of peremptory strikes altogether. A recent California law bars attorneys from removing prospective jurors based on a host of demographic factors, including gender and sexual orientation.

Washington state adopted a court rule in 2018 with stricter restrictions on racial discrimination, even if it’s not purposeful. The rule also bans a handful of reasons for removing someone, including living in a neighborhood with a high crime rate and receiving state benefits.

Lila Silverstein, a defense attorney with the Washington Appellate Project, who helped to draft the rule, said it took time to convince both prosecutors and defense attorneys that letting go of some of their power to dismiss jurors would create a system that “is actually more fair and more neutral and less biased.”

But nearly five years after the rule took effect, she said, attorneys are asking to strike jurors less often and judges are blocking race-based dismissals more. She said judges and attorneys also seem to be more aware of their implicit biases.

“The sky has not fallen,” Silverstein said. “Instead, things have gotten better.”

Lawsuit alleges lifetime jury ban harms Black New Yorkers and undermines democracy