NJ Temp Agencies Are Cramming Workers Into Vans During Pandemic

June 12, 2020, 8 a.m.

WNYC/Gothamist observed the practice this week.

It’s 5:30 a.m. and Reynalda Cruz was sitting in her car outside a pharmaceutical warehouse in East Brunswick, New Jersey. She was counting workers as they spill out of vans and shuttle buses.

“Oh my God, there’s more,” she exclaimed as three more vans pull up. Cruz counts 16 people in a vehicle meant to hold 15.

“It's like there's no pandemic,” she said in Spanish. Even the small minivans are packed with workers arriving for the early shift at Raritan Pharmaceuticals. She recognized the drivers from temp agencies around New Brunswick and Passaic.

Riding in stuffed vans is a known nightmare for temp workers in New Jersey who fuel much of the warehouse labor in the state. But as recently as this week WNYC/Gothamist observed that practice continues, even as state officials urge people to socially distance to halt the spread of COVID-19.

Labor and immigrant groups are calling on Governor Phil Murphy to boost protections for workers who are keeping businesses running during the pandemic. They say too many workers, particularly immigrants employed by blue-collar temp agencies, are slipping through the cracks. Many are getting sick and some have died.

“We need our state to step up to protect all workers, especially the most vulnerable, especially temp workers,” Sara Cullinane, executive director of Make the Road New Jersey said.

Listen to Karen Yi’s report on WNYC:

Cullinane said in the absence of state protections—and enforcement —Murphy needs to empower workers so they have the right to refuse dangerous work conditions without risking retaliation. Murphy’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

His administration has capped capacity on public transit at 50 percent and mandated new cleaning protocols during the pandemic. But the Division of Consumer Affairs—which oversees temp agencies—says that order does not apply to private vehicles provided by temp firms. Some of the vehicles are owned by the temp agencies; others are subcontracted.

Carmen Martino is a labor history professor at Rutgers University. He explained the temp industry is already largely unregulated. When you add a pandemic to the mix, “then you really do have the makings for a new version of the Wild, Wild West.”

Cruz, a former temp worker turned immigrant organizer with New Labor, said workers who lost their jobs during the pandemic are increasingly turning to temp agencies because many of them never shut their doors during the health crisis.

WNYC/Gothamist spoke to six workers who took rides in temp agency vans or from a third party during the outbreak. All of them said the vehicles were always at or near capacity. Four of them said they eventually came down with COVID-like symptoms.

Damian Silva works at JM Staffing Solutions in New Brunswick. With no car, he relies on the agency for transportation. That’s $9 dollars a day automatically deducted from his check.

“They’re very dirty and in bad condition,” Silva, 60, said of the vans which he described as littered with discarded masks and gloves. “With these illnesses, it can be contagious.”

State records show there are 330 registered agencies in New Jersey though not all of them specialize in blue-collar jobs. Numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show activity in many industries has dropped. Some warehouse work, however, never stopped.

Martino said warehouses are part of a supply chain that rely on cheap labor provided by third party temp agencies. Those agencies are an appealing employment option for low-wage undocumented immigrants.

“Because there's no safety net, because there's no unemployment for undocumented workers, temp agencies sort of become in a very strange way, the only social safety net that undocumented workers have,” he said.

In New Jersey, the blue-collar temp industry popped up to absorb a growing population of cheap labor. Martino said agencies set up shop in densely-populated immigrant-heavy cities like New Brunswick, Elizabeth and Passaic creating what he calls "temp towns."

“They would recruit right out of the neighborhood because the workers didn't have driver's licenses. So it was like a ready made workforce that you had absolute control over,” he said.

WNYC/Gothamist analyzed the list of registered temp agencies. JM Staffing in New Brunswick and Temps4U in Passaic—both companies that workers said transported them in packed vans—weren’t listed. Representatives at both agencies did not respond to questions about why they were operating without a license. DCA said it issued a notice of violation to Temps4U on June 5 for failing to register; the company faces a $4,000 fine.

Maria, who did not want her last name published because she is undocumented, turned to a temp agency when she lost her job at a restaurant that shut down during the outbreak.

She said the name of the temp company, Super Staffing in Passaic, wasn't on her checks. The agency, which is also not listed on the state list, did not return a call seeking comment.

Super Staffing assigned her to Jimmy's Cookies, where she packaged baked goods. After working there for a week in March, she started to feel sick.

“I started with a headache, and then I got chills,” she said in Spanish.

A co-worker told her a man on her same overnight shift died from COVID-19. But Maria, 40, never got tested. She was afraid she couldn't afford it.

Jose Luis, the worker who died, also worked with Staffing Solutions. His family declined to comment but issued a statement through Make the Road New Jersey. The family said they hoped Jose Luis’ death made warehouses take necessary precautions to avoid more victims.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration is the federal agency that enforces workplace safety. It has a pending investigation into conditions at Jimmy's Cookies, a spokesperson said. One of the owners of Jimmy’s Cookies, Michael Pisani, said the company implemented precautions in mid-March and have not had any more cases of COVID-19. He said it was difficult to buy personal protective equipment because they had to compete against the state government and hospitals for the same supplies.

Maria no longer works for the agency. She said even if conditions at the warehouse improved, workers still take the same crowded and dirty vans home.

“Who are the people who are risking their lives and going to work to those factories? To those agencies? It's us, the immigrants. For what? So people who are citizens and who are getting help have something to eat,” she said.

Cullinane, of Make the Road New Jersey, said temp agencies often take advantage of workers desperate for a job -- and that’s only exacerbated by the pandemic. According to the National Employment Law Project, temp agency workers made up 60 percent of the workforce in warehouses in 2018.

“Temp agencies have a long track record of skirting the law, as a result of COVID many have gotten sick and died and gotten their families sick,” Cullinane said.

Workers also say the agencies are violating state law by refusing to pay out sick days. One worker said JM Staffing required proof of a COVID-positive test. Another said the same agency declined to pay sick days because she didn't follow the proper procedure to call out.

JM office employees said workers need a doctor's note and if they can't afford to get care, they need a note from a pharmacist when they buy medicine. Otherwise anyone who doesn't feel like working can just claim they're sick. The employees referred questions to a manager who said he would pass along the message to another manager. Neither returned WNYC/Gothmist’s calls.

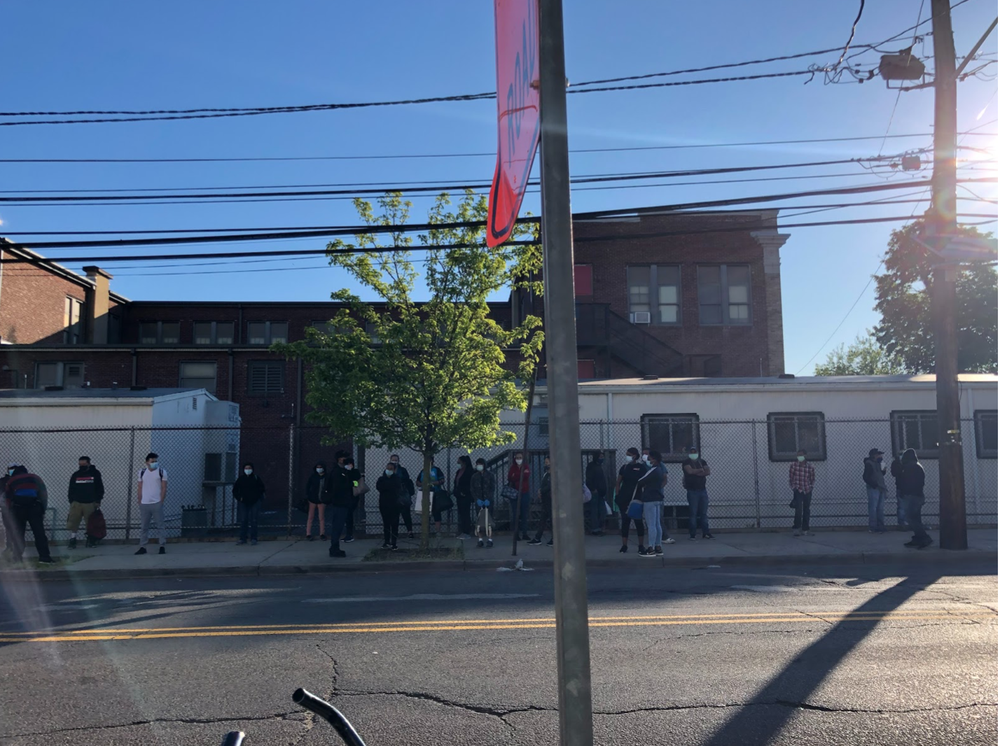

New Brunswick's temp agencies are located just a few blocks from one another. Inside their offices, there are signs everywhere reminding workers to wear masks. Plastic dividers separate the office staff from warehouse workers waiting in spaced out seats.

Narciso Rodriguez is an employee at On Target -- an agency that is registered by the state across multiple locations. He said they make sure the buses they hire only operate at half capacity -- or they'll call for a second ride. Vehicles are cleaned with Clorox, only one person rides in each seat and he personally inspects the buses before they head out.

“If 30 people fit, then 14 or 15 people will go,” he said.

On a recent Monday, dozens of workers waited for their bus. One arrived with a couple people already inside. Rodriguez told workers to wait. The bus left and a few minutes later two buses arrived to ferry workers to different job sites.

Cruz, who watched across the street, said the agency called another bus because she was there.

The following week there were nearly two dozen workers waiting for a ride. This time, only one bus arrived to pick them up.