NIMBYism delays plan for Bronx's first overdose prevention center amid crisis

June 28, 2023, 5:01 a.m.

The nonprofit St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction wants to open the borough's first safe injection site, which could save lives. The plan is now delayed due to a lack of public funding and community buy-in.

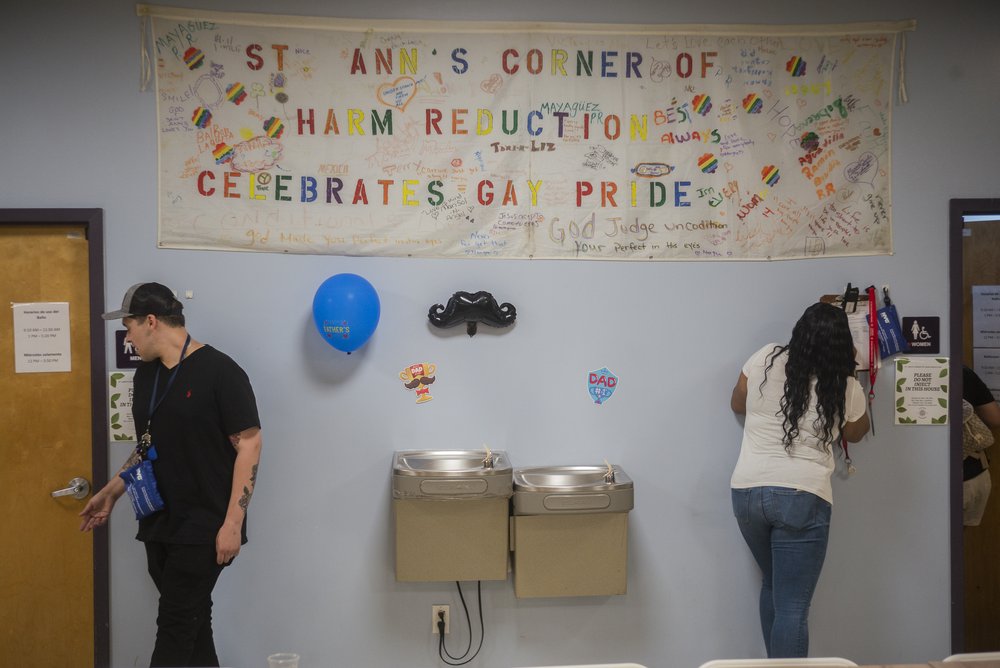

The lobby at St. Ann's Corner of Harm Reduction in the Bronx. The center is working to open the first overdose prevention center in the borough, but the plan is facing delays amid a quest to obtain community buy-in and funding. All this as the South Bronx leads the city in drug overdose deaths.

St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction in Longwood is working to open the first overdose prevention center in the Bronx – but the plan is facing delays amid the quest for community buy-in and funding.

Year after year, the South Bronx leads New York City in drug overdose deaths, and neighborhoods there are facing a harder toll as fatalities continue to rise. Mayor Eric Adams has identified the area as a priority location for a new overdose prevention center. These facilities, which are also known as supervised injection sites, let people use risky illicit drugs like fentanyl under the oversight of trained staff.

But St. Ann’s is caught amid an ongoing debate over where these sites should be located and whether they will attract more drug activity to surrounding neighborhoods.

The center has been providing drug users with clean needles and other services in its current location for 10 years, but the area still doesn’t have as much public drug use as other parts of the district, said Councilmember Rafael Salamanca, who represents the South Bronx. He worried that adding a supervised injection site would attract more.

“I do support the safe injection sites,” said Salamanca. “My only concern is the locations where you put them.”

A spokesperson for St. Ann’s first approached Gothamist in late May with the news that the community center would be opening a supervised injection room by the end of June.

But that plan had been scrapped by the time Gothamist toured the site on Westchester Avenue last week. After succumbing to pushback from Salamanca and the local community board, St. Ann’s CEO Joyce Rivera is now pursuing an alternative plan that requires moving her entire facility to a different part of the Bronx and securing real estate that can also house the array of other services that St. Ann’s offers.

“I've grown really impatient,” said Rivera, whose organization identifies itself as the longest continually running syringe exchange program in the U.S. “People are dying on our doorstep.”

New York City became home to the first two overdose prevention centers to openly operate in the U.S. in November 2021. The sites, which are operated by the nonprofit OnPoint NYC and located in Harlem and Washington Heights, have reversed nearly 1,000 potentially fatal overdoses in their first 18 months, according to the facility’s recordkeeping.

Mayor Eric Adams says he wants to open five more overdose prevention centers by 2025 as part of an effort to reduce drug deaths across the city by 15%. But these centers have long struggled for financial support because regulators still consider them illegal on a federal level.

- heading

- What’s an overdose prevention center?

- image

- image

- None

- caption

- body

- Overdose prevention centers, also known as supervised injection sites, seek to make illicit drug use safer by taking it out of settings like parks and public bathrooms.

- Participants bring their own drugs that they buy off the street and are able to use them in a designated room where they are provided with clean needles or other drug paraphernalia.

- Staff at these centers are trained in how to quickly spot an overdose, so they can intervene in a timely manner with remedies such as oxygen or the overdose reversal medication naloxone. They can monitor participants to make sure they’re OK and are able to call 911 if necessary.

- The two overdose prevention centers that operate in Upper Manhattan have reversed nearly 1,000 overdoses since opening 18 months ago, and no deaths have been reported.

City and state contracts already help fund St. Ann’s existing operations. In addition to providing clean needles, St. Ann’s offers hot meals, free clothes and communal activities ranging from anger management groups to talent shows. The center also has an onsite doctor who writes prescriptions for buprenorphine – a medication to treat opioid addiction – for those who want to stop rolling the dice on the underground drug supply.

Employees monitor the bathrooms at St. Ann's.

The cost of adding a supervised injection room would mostly be limited to staff salaries. It would pale in comparison to purchasing and building out a new facility, which Rivera prices at roughly $11 million. Rachel Vick, a spokesperson for the city health department, did not respond to a request for comment on whether the city would provide the funds that St. Ann’s requested for a fresh location.

“As we’ve said publicly, and laid out in the mayor's mental health agenda, we are working to expand the number of overdose prevention centers in New York City [and] working with community partners to determine appropriate locations and explore how we can get these lifesaving services to more people," Vick said.

Three neighborhoods in the South Bronx had the highest rates of overdose deaths in 2021 as well as the biggest increases from the year before, according to the city’s latest data. Although heroin has long been a problem in the borough, the rise of more potent synthetic opioids like fentanyl have made illicit drug use increasingly risky, Rivera said.

Moving drug use out of the bathroom

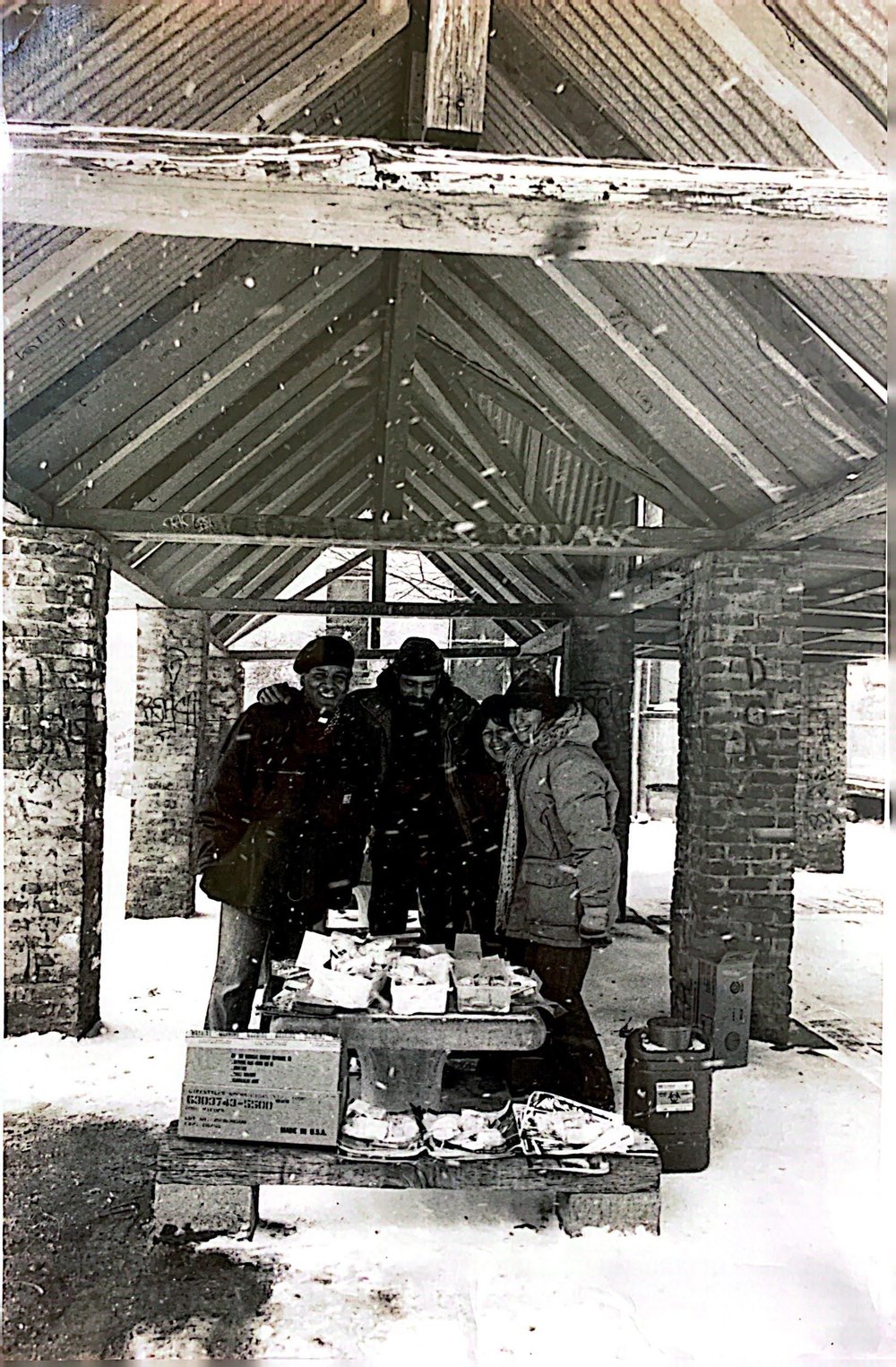

The origin of St. Ann's Corner dates back to the 1990s, when Rivera (third from the left) and a crew of volunteers used to hand out clean needles in parks.

Rivera is no stranger to wading into murky legal territory. St. Ann’s started with Rivera handing out clean needles in a nearby park in 1990, at a time when shared syringes were major spreaders of HIV. The underground experiment grew into a state-sanctioned syringe exchange site that ultimately added food, health and wellness services.

The cafeteria was joyful and bustling at lunchtime last Tuesday as participants chatted, watched TV and used the exercise equipment set up in one corner. But there were also signs of the current overdose crisis everywhere.

“You just never know when someone will have a fentanyl-related overdose,” Rivera said. “They don't have to inject it. They could just snort it. You could be standing in line and the guy or the woman behind you can just fall out.”

The lunchroom was outfitted with an oxygen tank and a defibrillator, and bright blue kits containing the overdose reversal medication naloxone were scattered throughout the facility. Staff members solemnly stood watch next to the bathrooms, timing how long people were inside.

“It's very difficult because we didn't hire these folks to become bathroom monitors,” Rivera said. “We have to rotate them every hour. It gets anxiety-producing for them.”

Rivera has long been eager to replace this ad hoc system. But she hesitated in late 2021 when former Mayor Bill de Blasio approached her with the opportunity to be among the first to open a safe injection site with the city’s support.

“We wanted to make sure that our community would be receptive to it,” Rivera said.

When de Blasio instead fast-tracked OnPoint’s centers in Harlem and Washington Heights, some in those neighborhoods were outraged that they weren’t given advance notice. “They knew there would be community pushback,” said Xavier Santiago, chair of Manhattan Community Board 11 in Harlem.

His community board had passed a resolution earlier that year calling for a moratorium on new drug treatment centers in the area, citing data that the majority of those using the services came from outside the neighborhood. A group called the Greater Harlem Coalition has been pushing a similar agenda, calling for more equitable distribution of drug services across the city.

According to Adams and Dr. Ashwin Vasan, the city's health commissioner, the two centers that opened prove overdose prevention centers can save lives – but they continue to draw criticism from some neighbors.

The facilities are designed to reduce public drug use, and outreach teams collect syringe litter in their surrounding areas. But there have also been reports of some participants using drugs at nearby subway stations once the facilities close for the night.

OnPoint recently responded by extending its hours in Washington Heights and plans to do the same in Harlem, with the goal of eventually operating both locations 24/7, according to Reggie Johnson, an OnPoint spokesperson.

Meanwhile, Greater Harlem petitioned state lawmakers this year to reject a bill that would have created more overdose prevention centers, unless they added certain “guardrails.” These included requiring the centers to be located a certain distance from schools, putting more resources toward policing the areas outside the facilities, and requiring the programs to offer more data on their outcomes – including efforts to connect participants to treatment.

Researchers at NYU Langone recently received federal funding to study the impact of OnPoint’s overdose prevention centers on their participants and the communities where they operate – but that study won’t be completed until 2027.

In the meantime, Greater Harlem said, the city should “open many supervised injection sites or none at all.”

A change of plans

Roberto Crespo, the chair of Bronx Community Board 2, lives near St. Ann’s and said the area has already been “inundated” with social services. “This community board has stated already that we have had enough — enough shelters, enough drug treatment programs, enough of everything,” Crespo said.

Crespo and Councilmember Salamanca have both pushed Rivera to instead open an overdose prevention center near The Hub, a bustling commercial center at 149th Street and Third Ave. The Hub is easily accessible by public transit and, according to locals, there’s rampant outdoor drug use nearby.

Rivera agrees that the area would be ideal. But there’s no clear timeline yet for how long it will take to move her whole operation. In the meantime, she had been hoping to launch at her current site at least on a temporary basis.

She said she plans to buy, rather than lease, real estate for the new facility, so that it will have more long-term stability. One of the sites Rivera is considering is the ground floor of 600 Bergen Ave., which is part of an affordable housing complex a few blocks from the Hub. Purchasing and building out the space would cost the estimated $11 million, Rivera said.

Salamanca wrote a letter in April to Adams and Vasan, asking them to provide St. Ann’s with the $11 million using money the city has received from legal settlements with pharmaceutical companies. The settlements resulted from lawsuits against the companies for their role in promoting opioid use. The city is slated to take in $150 million over five years.

In the past, Adams has declined to use opioid settlement dollars to directly fund overdose prevention centers – although the administration is not averse to funding the wraparound services the nonprofits operating the sites offer.

City officials “have really narrowed down” the services they consider to be directly facilitating illicit drug use, said Charles King, the CEO of Housing Works, another nonprofit seeking to open an overdose prevention center.

Bronxites living near the Hub who spoke to Gothamist last week were split on whether they thought an overdose prevention center would help reduce public drug use in the area or exacerbate the problem. But Rivera has yet to make an official presentation about the proposal to Bronx Community Board 1, which covers that area, according to a member of the Board who spoke anonymously because they weren’t authorized to speak to the press.

Even if there is some community opposition to the new location, Rivera will move forward with the plan to open near the Hub, said Henry Robins, a spokesperson for St. Ann’s.

Overdose prevention centers save lives but remain in legal limbo, as NYC moves toward expansion How NYC hospitals are using artificial intelligence to save lives