Nearly Three Months Out, We Have A Clear Picture Of COVID-19 Vaccine Safety

March 3, 2021, 12:34 p.m.

After tens of millions of shots, there has been no significant increase in the risk for adverse consequences. And the early data on pregnant women look good, too.

Last month, when a man collapsed and died after getting vaccinated for COVID-19 at the Javits Center—shortly after the 15-minute observation period in which recipients are monitored for adverse reactions—many news outlets reported that health officials did not believe it was related to the vaccine.

But they left the possibility open, just a crack. The incident might have served as one more seed of doubt for those still skeptical of the vaccines, which were developed and rolled out at a record pace.

Now, New York City’s medical examiner has shared the details on the man’s death with Gothamist, a six-word determination reading “Hypertensive and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease/ Natural.” He died of natural causes—a heart condition—unrelated to the vaccine. And ongoing surveillance of reactions to the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines has not produced any results that would call their overall safety into question.

Now that nearly 80 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have been administered, any serious issues likely would have come to light, said Dr. Paul Offit, a renowned virologist and immunologist who directs the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He often quotes vaccine pioneer Maurice Hilleman, who developed more than 40 vaccines in his lifetime, as saying, “I never breathe a sigh of relief until the first three million doses are out there.”

Offit is also a realist. He can rattle off a litany of instances throughout history when a vaccine has caused serious negative reactions. Clinical trials are built to catch side effects, but in rare circumstances, they might miss a serious one because of the limited number of people enrolled. That happened with the original rotavirus vaccine in the late 1990s after it went through clinical trials. But in that episode and others, the side effects showed up in the short term, not months or years down the line.

I can think of no example of a vaccine that 10 or 15 or 30 years later caused something that wasn’t picked up initially.

Dr. Paul Offit, Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

“There really is no serious side effect that hasn’t occurred within six weeks of the dose. I can think of no example of a vaccine that 10 or 15 or 30 years later caused something that wasn’t picked up initially,” said Offit, who is also a member of the FDA advisory committee for COVID-19 vaccines.

Indeed, the early rollout of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines revealed that, in very rare cases, people could experience an allergic reaction, typically within 15 minutes of receiving a shot. It’s a reaction that can be reversed with an EpiPen injection. That’s why recipients are now monitored after receiving the vaccines. The most common effects felt shortly after getting the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are mild—such as headaches or fatigue—and are thought of as a sign that the shots are working. That malaise typically disappears within a couple of days and can be treated with pain relievers if taken at the appropriate time.

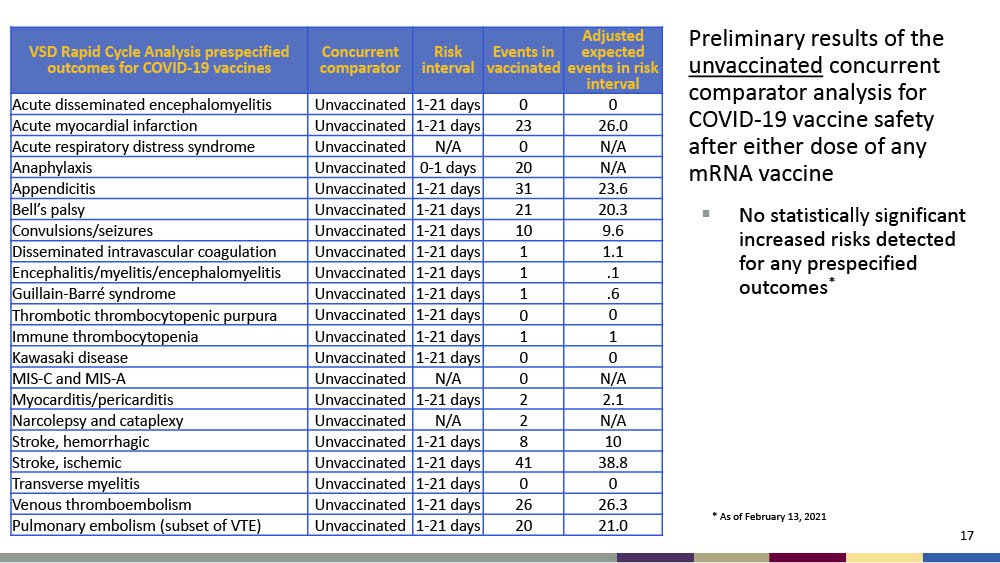

Otherwise, clinical trials for the vaccines have shown that they are overwhelmingly safe and effective. During the authorization hearings for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, Tom Shimabukuro of the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force provided an update on the national safety monitoring for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccine rollout, showing that there was no significant increase in the risk for adverse consequences after the first 55 million doses were delivered through mid-February. When their task force looked at an array of conditions, ranging from appendicitis to stroke to heart attacks, they found the number reported among COVID-19 vaccine takers matched what was recorded normally among the unvaccinated.

Since the COVID-19 vaccination effort began a few months ago, local and national health officials have been beating the drum of vaccine safety. It’s a message that New York politicians and health officials have realized they have to work harder to communicate in certain communities throughout the city where vaccine hesitancy is suspected to be high and trust of the government is not. This is partly a result of the same poor record of health care access and outcomes that made those areas more vulnerable to COVID-19 in the first place.

Aside from concerns about general safety, one of the most common questions Mayor Bill de Blasio says hesitant New Yorkers raise is about the vaccine’s effects on fertility. Online rumors have stoked fears that COVID-19 vaccines can cause infertility or cause pregnant women to miscarry. But scientists say they have no basis in fact.

“Many of us are doing a lot to try to counter that narrative,” said Dr. Richard Beigi, who studies immunizations and therapeutics in pregnant and lactating women and co-authored recommendations on the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Number one, there’s absolutely no scientific reason to believe that there’s any link to infertility with these vaccines, or any other vaccines, for that matter. We have been giving non-live vaccines to pregnant women for various infections for decades with lots of success.”

Although pregnant women were not intentionally included in the clinical trials for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, about 20,000 pregnant women have taken them. They either became pregnant during the trial or gained access to the drugs based on their state’s eligibility. There have been “no red flags,” according to Dr. Anthony Fauci, who added, “This is being monitored by the CDC and the FDA.”

Shimabukuro likewise presented surveillance data showing practically zero pregnancy complications among the vaccinated. The most commonly reported event was miscarriage, with 30 recorded among a CDC registry of 1,800 women. But this number wasn’t above what might happen across the general, unvaccinated population, given miscarriages are tragically frequent among American women, affecting about 10 to 20% of pregnancies depending on age.

Beigi acknowledged that observational studies on pregnant women’s reactions to the COVID-19 vaccines are ongoing, and says it’s essential to continue to collect data. “Not because we’re afraid there’s a problem but more to validate the safety we have every reason to believe is there,” he said.

Beigi said he tells women that getting vaccinated is their choice but points out that it can benefit both them and their babies by protecting them against serious illness, which can be particularly dangerous in pregnancy.

Offit says it’s OK for people to be skeptical about vaccines, as long as their skepticism is rooted in reason and facts.

“I would argue I was skeptical way back in September and October,” he said. “If you asked me if I would get a COVID-19 vaccine then, my answer would be, ‘Not until I see the data.’”

Editor's note: This story was updated to clarify how many mRNA vaccines have been administered in the U.S. It's nearly 80 million doses overall, not 80 million recipients.