Mayoral challengers seize on child care fight, seeing vulnerability for Mayor Adams

Jan. 24, 2025, 3:27 p.m.

Early childhood has become a particularly sore spot for the mayor, who's facing backlash over the abrupt closures of five daycare centers.

When Stephanie Park’s first-born child was denied a spot in public 3-K, a financial dilemma familiar to many families across the city suddenly hit her home.

Park was on maternity leave with her second child, and anticipating a return to work in the financial services industry. Without the option of free 3-K, her family was looking at $59,000 per year to care for the two kids. She called the number “insane.”

“That is money that could be going towards a deposit on the apartment. It’s money that my household could be using to pay down student loans, to be saving in our kids 529 [college savings plan] accounts,” Park said.

Park’s predicament will sound familiar to many New York City parents – and it represents a key vulnerability for Mayor Eric Adams as he campaigns for reelection. Families have fled the city in recent years, driven out by skyrocketing costs including child care. Adams enraged parents and providers last year when he proposed steep budget cuts to the city’s pre-K and 3-K programs — as well as earlier this month, when his administration shocked daycare centers with abrupt closures. The mayor’s rivals seem to agree that child care is a ripe area for targeting the incumbent, though their plans include vast differences.

Adams restored most early childhood education funding last year after outcry from grassroots groups like New Yorkers United for Child Care, which Park joined out of frustration over last year’s budget fight. This year, his administration touted a budget proposal with no major spending cuts. But according to an analysis from city Comptroller Brad Lander, who is among Adams' challengers for the mayor's seat, the administration is proposing cuts to early childhood programs totaling $300 million — double what it tried last year.

“We all know that a budget is a reflection of our values,” said Robert Cordero, CEO of the Grand Street Settlement, which runs one of the five child care centers now on the chopping block. “So do we value child care that's affordable in New York City, or do we not?”

Elected officials, advocates and the candidates vying for Adams’ job would argue that they do, but they voice a range of opinions over what’s possible. Activists want a new universal child care program for the city’s 2-year-olds, while the city struggles to make its existing pre-K and 3-K universal. And not everyone agrees that “universal child care” should be free for all.

A menu of options for families

Last November, when New Yorkers United for Child Care launched its universal child care push, Lander, Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani, and state Sens. Zellnor Myrie and Jessica Ramos were all in the crowd. All four are now among the field of contenders gunning for Adams’ seat.

“It’s unfortunate to have to say that this mayor has us regressing when it comes to child care,” said Ramos.

While Adams has said he wants to make New York the best place to raise a family, his administration has offered little in the way of new early childhood programs.

Ramos said she wants to expand child care access by creating a portal that would let families apply for available seats in their language, and by making city agencies work more smoothly together to expedite providers’ licensing, background checks and safety inspections.

A mother of two and the only woman in the race, Ramos argued she’s the best equipped to improve child care access and affordability because she helped roll out the city’s universal pre-kindergarten program under former Mayor Bill de Blasio. She said that when she left city government for the state Senate, she’d hoped the city would continue to make progress on affordable child care.

“ What we didn't know is that we were going to end up with a Trump Democrat as mayor,” Ramos said, arguing that Adams treats child care and early childhood education as priority of the previous administration, not his own.

Mamdani, meanwhile, favors a less technocratic approach. He has a proposal for “no-cost child care” that would cover care for children as young as 6 weeks to 5 years old for all families, regardless of income, along with boosts in salary for child-care workers.

“This system would be universal, not means-tested, which reduces bureaucracy, builds political support and destigmatizes public services,” Mamdani said in a statement.

It comes with a hefty price tag. By his own estimates, Mamdani said the program would cost at least $5 billion in city funding, plus federal and state dollars. Additional revenue would come from taxing the wealthiest New Yorkers, he said.

“‘Universal’ is a great word until you have to pay for it,” Stringer, a father of two, said. His plan relies on an extended school day and what he’s calling the “NYC Tri-Share Childcare Fund.”

The fund would be a public-private partnership using city, state and federal dollars along with investments from employers, which would receive tax credits for participating. Families would then pay for the services on a sliding scale, with the lowest-income New Yorkers receiving the services for free, and those with higher incomes paying no more than 7% of what they make on child care and afterschool programs.

Stringer pointed out that a similar pilot program currently exists in Michigan, which saw an 80% increase in employee retention along with lower rates of absenteeism, according to the program's administrator.

Myrie is setting his sights on after-school programs. He said he wants to make sure all public school students in K-12 have access to after-school programming, regardless of where they live in the city.

“Right now, we have zip code-dependent afters-schooling and it is dependent sometimes on how wealthy the PTA is,” Myrie said during a recent appearance on "The Brian Lehrer Show." “I don't think that your zip code should determine whether or not you have access.”

Lander, who is expected to take a fundraising lead in the mayoral race next month, issued a report from the comptroller’s office this month that found that a family in New York City needs to earn $334,000 to afford the cost of child care for a 2-year-old. On average, the report found families were paying upward of $23,400 a year for child care, which is more than tuition at a CUNY institution.

Lander, also a father of two, backs a universal child care program, which his office found could increase labor force participation while increasing families’ disposable income by nearly $2 billion a year. His campaign has said it will lead the charge on securing the needed state and federal funds to provide it and increase wages for child-care workers.

He’s also a vocal critic of the Adams administration’s recent decisions to close child care centers.

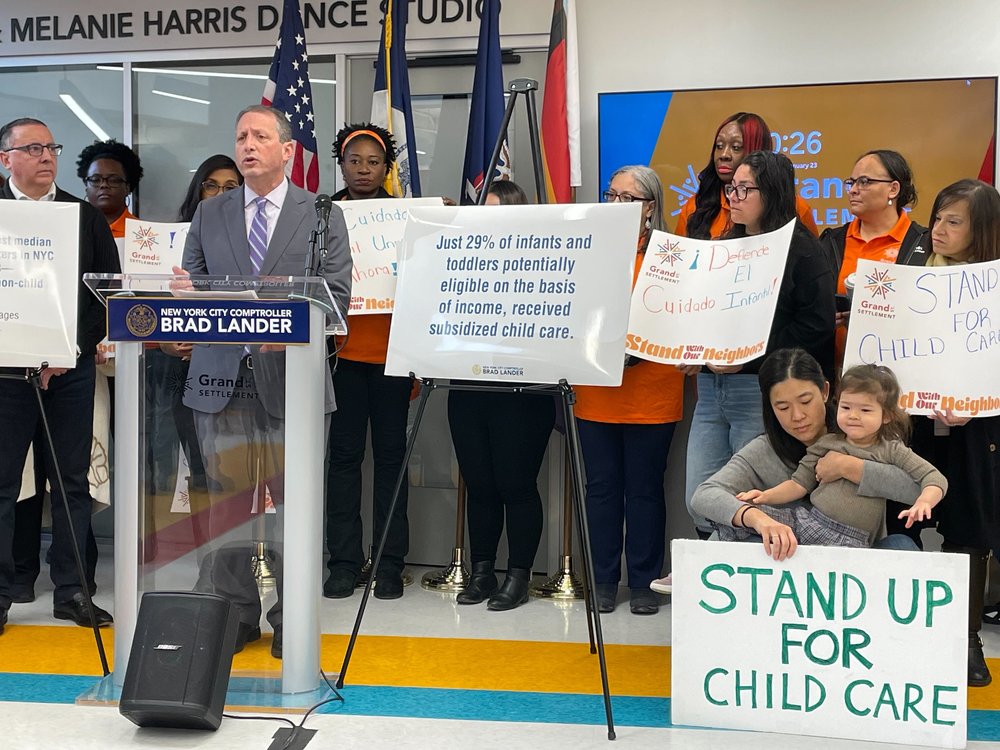

“ We've made this promise to families, but we are breaking it,” Lander said Thursday at a press event at Grand Street Settlement’s Lower East Side location. “That's what it would mean to keep these five daycare centers open.”

A critical moment for a system under scrutiny

In the three years after the start of the COVID pandemic, New York state achieved the dubious honor of leading the nation in population loss — driven by families leaving New York City, according to analysis from the left-leaning Fiscal Policy Institute.

That analysis found that people with children under 6 years old left the state at a 40% higher rate than those without young children, suggesting that costs unique to families, like child care, were key drivers.

Those departures cost the city, too. In 2022, NYC’s Economic Development Corporation, a nonprofit organization that focuses on increasing business development and increasing the city’s overall economic prosperity, found the city saw a “$23 billion decrease in economic output, a $5.9 billion drop in disposable income, and $2.2 billion less in tax revenues,” stemming from parents leaving their careers to attend to caretaking responsibilities.

Adams has said he is committed to ensuring every family who wants access to a 3-K and pre-K seat will get one. He frames his administration’s cuts as practical, saying it has been assessing whether the right number of seats are available in the right neighborhoods, and slashing underutilized programs. Several of the centers dispute the enrollment figures the city is relying on — and note that the city owes them millions of dollars in back payments.

“ When I took over as mayor, we noticed that we had far too many centers that were being opened and we didn't have pupils in there,” Adams said at a press conference Tuesday. “So we had to realign the system.”

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify that New Yorkers United for Child Care launched a campaign for universal child care in November.

NYC child care centers say city stalled payments before abrupt closures Families scrambling after NYC ends leases at 5 early child care centers