Mayor Adams' 2021 campaign stopped replying to NYC watchdog. It still got public funds.

June 14, 2024, 6:01 a.m.

Records obtained by Gothamist show a campaign that was interested in some rules and then ignored numerous information requests as cash flowed in.

A newly released trove of internal documents show that the team behind Eric Adams' mayoral bid was regularly seeking guidance from campaign finance officials long before Adams declared his candidacy.

But when the New York City Campaign Finance Board asked more questions about donations from small donors to ensure Adams' team was in compliance, the Adams campaign stopped replying. Gothamist obtained emails and other documents between the Adams campaign and the CFB between March 2018 and August 2023 in a public records request.

The campaign's early correspondence with agency officials shows Adams' team sorting through the many rules and laws around a public matching program, which generously amplifies small donations with taxpayer dollars but comes with specific limits and restrictions.

While Adams raised nearly $20 million for his 2021 campaign — including more than $10 million from the matching program — documents show that his team ignored the agency's questions about potential violations, even as they inquired about different ways they could spend their funds.

As the Adams campaign now faces state and federal probes, the correspondence offers new insight into its sprawling efforts to raise money and Adams' clout through various unconventional methods, like donations from a trust and promotions from fitness centers. The documents also show how the Adams campaign interacted with the agency on issues that are now reportedly under scrutiny from investigators.

Records also show that the CFB never withheld any full public matching payments from the Adams campaign despite never receiving answers about small donors and people who collected donations on behalf of the campaign.

The Adams campaign’s lax reporting on so-called intermediaries — people who help bundle donations on a candidate's behalf — and the use of illegal straw donors is now subject to several probes and has led to six indictments. And so far, four donors have pleaded guilty to violating campaign finance laws. The mayor and his campaign staff have not been accused of any wrongdoing.

The Adams campaign declined to answer questions about its fundraising reports. The CFB would not comment about its ongoing audit of the campaign.

A ‘nuclear bomb’ in a rat hole?

Although Adams previously held public offices, his mayoral run was the first time he accepted matching funds through the city’s public campaign finance program. Top staff from the Adams’ campaign sought guidance from the CFB on a broad range of issues, like how to record unusual donations made by wire transfer or from a trust, correspondence shows.

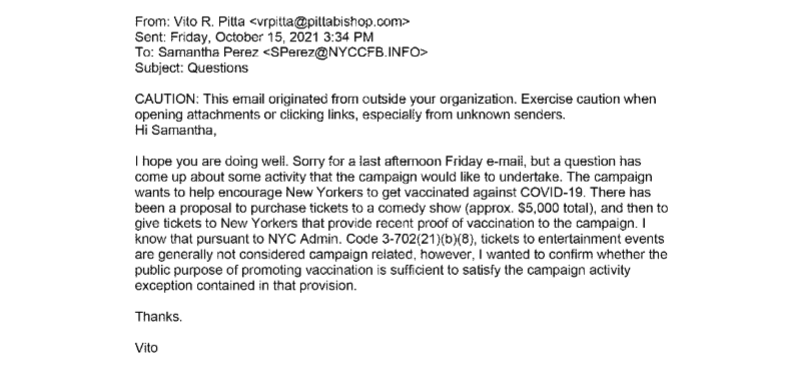

The campaign also inquired about whether it could expense trips to Puerto Rico for a political gathering, a poll on issues important to New Yorkers ahead of the November 2021 general election, and comedy show tickets to boost COVID-19 vaccination efforts, records show.

The campaign even inquired about the rules surrounding potential promotional events for Adams’ memoir “Healthy At Last,” including an email blast sponsored by the company that owns Equinox and Blink gyms. That email blast, which was planned to be sent to gym members, recommended Adams' book and noted that he was the Democratic mayoral nominee.

“We have no issue with that,” the agency’s general counsel said in an email to Adams campaign attorney Vito Pitta.

What the CFB did take issue with were the hundreds of donations it flagged during its ongoing compliance checks of the Adams’ campaign’s fundraising disclosures, which was required at periodic intervals ahead of the primary and general elections.

On at least 13 separate occasions between February 2019 and November 2021, ahead of the general election, the agency sent the Adams’ campaign a review of its donations, highlighting specific instances where the campaign needed to supply additional information. Each statement review included a letter from the agency reminding the campaign of what needed to be done to respond to its information requests and the deadline to respond by.

“Please note that responding to and/or correcting the preliminary findings identified in this review does not eliminate the possibilities that penalties may be assessed for violating the Campaign Finance Board Act or Rules,” warned Danielle Willemin, director of the audit division.

The agency flagged donations submitted for matching claims that were missing a New York City residential address or the donor’s employment information. The city’s matching system awards campaigns $8 in taxpayer money for every $1 they receive, up to $250 in a mayoral race, to incentivize smaller contributions from everyday New Yorkers.

The CFB also flagged hundreds of contributions that were either over the legal limit for individuals, prohibited donations from corporations or those made in cash over $100. Records show the Adams campaign was responding to the agency’s request for additional information through the Democratic primary in June 2021, but stopped submitting responses to questions about flagged donations a month later.

One issue the campaign never addressed were the several hundred donations that appeared to be collected by individuals on the campaign's behalf, the records show. Individuals known as intermediaries bundle contributions in an effort to gain stature and access to campaigns. Those bundlers are required to be disclosed to the campaign watchdog agency.

The four Adams donors who pleaded guilty to charges including conspiracy, falsifying business records and grand larceny, admitted to scheming to recruit their employees and family members to donate to Adams’ campaign while illegally reimbursing them, circumventing donation limits and exploiting the city’s matching funds program.

Donations from one of the company’s implicated in the straw donor scheme, EcoSafety Consultants, had been flagged by the CFB as far back as May 2021. Donations from people at other companies, including the Turkish-owned KSK Construction Group and Jmart Group, an Asian-American grocery store chain, have also been flagged as potential straw donor contributions.

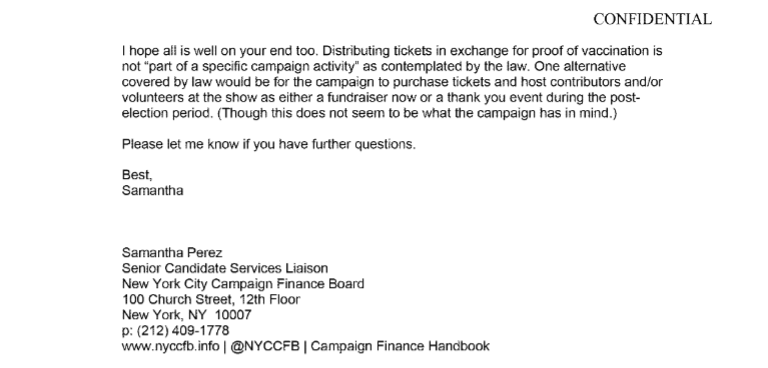

The CFB reviews each campaign’s periodic filings and sends them a compliance checklist, which includes donations they have questions about. Campaigns are required to review the list and respond to each type of inquiry. The campaign marks which reports it has addressed, and signs and dates the document under a statement that notes the criminal penalties for providing false information.

The Adams’ campaign submitted partial responses to nine of the CFB's reviews through the June primary election. But it never addressed questions about suspected intermediaries before or after his election.

An Adams campaign attorney declined to answer questions about why the campaign did not respond to any of the suspected intermediaries' report inquiries ahead of the November 2021 election or why the campaign did not submit any other statement review checklists after July 1, 2021.

“We won’t comment on issues that are part of the ongoing collaborative post-election audit with the CFB,” Pitta said in a statement.

The Adams campaign has consistently said that it disclosed any individual who bundled donations and qualified as an intermediary.

The campaign reported a total of four intermediaries for its 2021 campaign, financial disclosures show, far fewer than the 26 bundlers Adams reported in his 2013 campaign for Brooklyn borough president. By comparison, Kathryn Garcia, who narrowly lost to Adams in the Democratic primary and received more than $6 million in public funds, reported 40 intermediaries in her disclosures.

According to the city’s campaign finance law, candidates are supposed to identify anyone who collects and submits donations on their behalf as long as that person is not the candidate’s spouse, domestic partner or immediate family member. People who host fundraising events that the campaign pays for also don’t need to be identified as bundlers.

Under the agency’s penalty guidelines, if the CFB determines that a campaign failed to disclose an individual who bundled donations for them, the campaign could be fined $100 for each individual it neglected to disclose, an amount that some say might not be much a deterrent when a campaign is raising millions of dollars for a citywide race.

“It’s the cost of doing business,” said Sarah Steiner, an election attorney in Manhattan.

The CFB can issue more severe penalties if it determines that a campaign knowingly submitted false documentation, but those penalties are assessed after the agency completes its audit process, which sometimes takes years. It can also refer any suspected illegal activity to prosecutors.

A proposed bill at the City Council would give the CFB the ability to withhold any public matching funds if a campaign doesn’t respond to requests for more information. But the measure backed by Councilmember Lincoln Restler is so far receiving a chilly response.

John Kaehny, executive director of the government watchdog group Reinvent Albany, said he thought that policy change was blowing the intermediary issue out of proportion.

“You have a rat hole so you put a nuclear bomb in it? Is that what you want to be doing?” said Kaehny.

6 months after FBI raid, investigations into Mayor Adams’ fundraising have only grown Accused conspirator in donation scheme for Mayor Adams' campaign pleads guilty NYC Mayor Adams’ fundraiser Brianna Suggs hires new lawyer amid federal probe into campaign