Maimonides evicts current and former hospital workers from buildings converted into NYC affordable housing

Oct. 17, 2023, 6 a.m.

The group being evicted consists primarily of hospital retirees and other former workers who were never offered alternative housing. It also includes current employees who refused to move after being offered employee housing in other buildings.

Owen Denoon left his job at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan to become a nurse at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn’s Borough Park in 1989. He said he was still finding his footing in the city after moving from Trinidad and Tobago, and the employee housing Maimonides offered was one of the perks that incentivized him to make the switch.

“It was well known that any new hires that wanted housing, it was readily available,” said Denoon, now 67.

He moved into an apartment in a building Maimonides owned a couple of blocks from the hospital after his hiring and has lived there for the past 34 years. When he retired in late 2020, after surviving the most treacherous phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, Maimonides let him stay.

Now, at a time when rents across the city are sky-high and homelessness is reaching new peaks, the hospital wants him out.

Denoon is one of at least 38 current and former Maimonides employees who are in the process of being evicted from their apartments by the medical center, according to court filings. Most of the pending cases were filed this year.

- heading

- Story at a glance

- image

- image

- None

- caption

- body

- Maimonides Medical Center is evicting at least 38 current and former employees from buildings that previously served as employee housing. In 2018, the nonprofit hospital sold a portfolio of buildings to the private developer Iris Holdings Group for about $68 million.

- Many of those tenants are being kicked out of buildings that are being converted into affordable housing as part of a deal with the city government to address the homelessness crisis. The city said Maimonides is solely responsible for the evictions.

- Maimonides offered current hospital workers employee housing in other buildings. The hospital did not provide a similar alternative for retirees or other former workers.

- The conflict involves 140 apartments across seven buildings near the hospital in Borough Park. The buildings are located at 1016 50th St.; 5001 10th Ave.; 864 49th St.; 983 46th St.; 902 47th St.; 914 47th St.; and 926 47th St.

- Maimonides is also suing the tenants being evicted for thousands of dollars in back rent. Some who spoke to Gothamist denied owing Maimonides money.

Those affected include retirees as well as people with disabilities who are on fixed incomes, some of whom have lived in their apartments for decades. One developed chronic physical and psychiatric conditions while working at Maimonides, according to medical records and human resource documents he shared with Gothamist.

But they’re not going quietly. At least 20 of the tenants have been granted permission to combine their cases in court and make a joint argument against the hospital, according to Legal Aid Society attorneys representing some of this group.

The mass eviction is the aftermath of Maimonides selling a portfolio of its Borough Park properties to the developer Iris Holdings Group for $68 million in November 2018. That company (under the moniker Park Affordable LP) then inked a deal with the city government to renovate some of those buildings and convert them into affordable housing for low- and middle-income New Yorkers, in exchange for a property tax break.

But the tenants connected to Maimonides, who were already paying below-market rates, are being squeezed out as part of the deal, which included a lengthy transition period. Some said their monthly rent rose nearly 32% after the sale.

“It’s inhumane,” Denoon said. “I spent all my working career at Maimonides. They benefited from my life.”

The group being evicted includes a handful of current employees who refused to move after being offered employee housing in other buildings, but is primarily made up of retirees and other former hospital workers who were never offered alternative housing.

Many of the tenants who are being evicted were able to pay below-market rents by taking advantage of Maimonides’ employee housing, which hospital spokesperson Suzanne Tammaro said the medical center began offering more than 40 years ago to “ease housing burdens for medical residents, fellows, and other healthcare professionals.” Since then, rents across the city have risen to punishing highs, while rent-regulated apartments have become harder to find.

Maimonides’ employee housing options became “very desirable” and people increasingly stayed long-term, including after they stopped working for the hospital, Tammaro said.

But in a somewhat ironic twist, the designation of these apartments as employee housing – rather than traditional rentals with formal leases – put the occupants in a much more vulnerable position once Maimonides was ready to sell the buildings. At this point, some of the occupants haven’t worked for Maimonides for years and argue they should be entitled to stronger tenant protections and, in some cases, coveted rent-stabilized leases.

Maimonides contended in eviction filings that it already went above and beyond its legal obligations to keep tenants housed after they ended their employment with the hospital. The medical center then gave tenants years to move out after the buildings switched hands, Tammaro said.

When Maimonides made the sale, the hospital signed a master lease with the new owner to rent all the apartments that were still occupied by current and former hospital employees, and then sublet them to the individual occupants. The agreement covered 140 apartments across seven buildings.

One current Maimonides employee affected by the deal shared a notice the hospital sent to tenants at the time alerting them of the sale and letting them know that they could stay in their apartments — albeit with a schedule of regular rent increases. The notice didn’t include a deadline for them to move out. Other tenants said they received similar notices.

Gothamist spoke to eight of the tenants now facing eviction. They said they were never clear on how long they would be allowed to stay — until they received warnings saying that they had to be out in 90 days. For most of the tenants now in court, those notices arrived between November 2022 and February 2023 – more than four years after the buildings were sold. Those who spoke with Gothamist said they were never contacted by the new owners about the possibility of obtaining a lease in one of the vacant apartments.

Tenants also shared complaints about Maimonides being unresponsive to needed repairs in recent years and said they were frequently left to deal with pests, leaky ceilings and broken plumbing themselves. Per the master lease, the hospital was still responsible for repairs within the apartments covered by the agreement, while the new owners took care of common areas.

The seven buildings covered by the master lease currently have a total of 385 open violations with the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) – including 153 at 1016 50th St., where Denoon lives. That’s about 1.4 open violations per apartment across the seven-building portfolio – above the citywide average of 0.8.

Maimonides “has endeavored to be responsive to repair requests,” Tammaro said. But she added that there’s a difference between repairs and “improvements,” which she said some tenants made to their apartments without permission.

The master lease was supposed to be a temporary stopgap that would remain in place for just two years while the Maimonides tenants relocated. But it was extended indefinitely amid the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Tammaro. Current employees were offered units in other buildings owned by the hospital, she said. She added that the majority of the apartments the master lease covers have now been vacated.

In January 2022, New York state lifted its pandemic-era ban on evictions, and those housing removals have since been on the rise.

Tammaro said maintaining the buildings was becoming a liability. Of the tenants being evicted, 29 owe an average of more than $21,000 in unpaid rent, she said. Some of the tenants who Maimonides is suing for back-rent denied the allegations to Gothamist. Maimonides alleges in court materials and its statement to Gothamist that some tenants have sublet their apartments.

“We believe, as a safety-net hospital and consistent with our core mission, that the funds previously utilized to maintain these properties are more appropriately directed to caring for our patients,” Tammaro said in a statement.

In 2022, Maimonides Medical Center brought in nearly $1.7 billion in revenue and had about $138 million in net assets at the end of the year, according to the latest annual financial statements from the hospital. But the hospital still lost nearly $130 million on operations, only a slight improvement over the previous year’s nearly $145 million operating deficit.

[Iris Holdings Group] has never pursued a single eviction against Maimonides Medical Center or their occupants.

Iris Holdings Group via its lawyer B. David Schreiber

New York City’s deal with Iris Holdings Group includes language calling for the housing removals. The affordable housing agreement the new building owner signed with HPD in 2021 states that the owner shall make "commercially reasonable efforts to cause Maimonides Medical Center to relocate the employees in the employee occupied units."

But officials at the Department of Housing Preservation and Development were under the impression that all of the Maimonides tenants were current workers who would be offered employee housing elsewhere, said HPD spokesperson William Fowler.

“HPD’s agreement provides a way out of shelter to homeless families, it provides Section 8 housing vouchers to vulnerable New Yorkers, and it provides deeply affordable homes to both low- and moderate-income New Yorkers at rents that are affordable to their incomes,” Fowler said in a statement. “In no way does this agreement require a deadline for hospital employees to leave.”

Both HPD and Iris Holdings Group denied any responsibility for the evictions.

Iris Holdings Group “has never pursued a single eviction against Maimonides Medical Center or their occupants,” the company said in a statement to Gothamist, via lawyer B. David Schreiber. “Our mission is to preserve and expand affordable housing for people in need.”

Meanwhile, Denoon said he is daunted by the prospect of having to look for a new apartment in the current market if he doesn’t win his eviction case.

“The rents are exorbitant. It’s truly rough,” Denoon said. “As a senior person, you have particular needs. You don't want to go into an apartment that doesn't have an elevator. You don't want to have to climb up three flights of stairs.”

The fight for a rent-stabilized lease

Freshly renovated gray-and-white apartments are now up for grabs in some of the buildings Maimonides sold, according to a website under the banner The Park Affordable.

They are advertised with phrases like “modern luxury,” “classic elegance,” and, interestingly, “Sunset Park,” an adjacent neighborhood.

One of the biggest selling points touted on the site is the apartments’ rent-stabilized status, which caps how much rent can go up each year.

Some of the Maimonides tenants who live in these buildings believe they are also entitled to rent-stabilization protections. But they are wading through murky legal waters.

Because Maimonides is a nonprofit hospital, it is permitted under state law to provide employee housing that is exempt from certain rent regulations, the same way a university would have greater discretion over student or faculty housing.

Maimonides confirmed that the tenants being evicted never signed formal leases when they moved into their apartments. Those who spoke to Gothamist said the hospital simply deducted the rent from their paychecks.

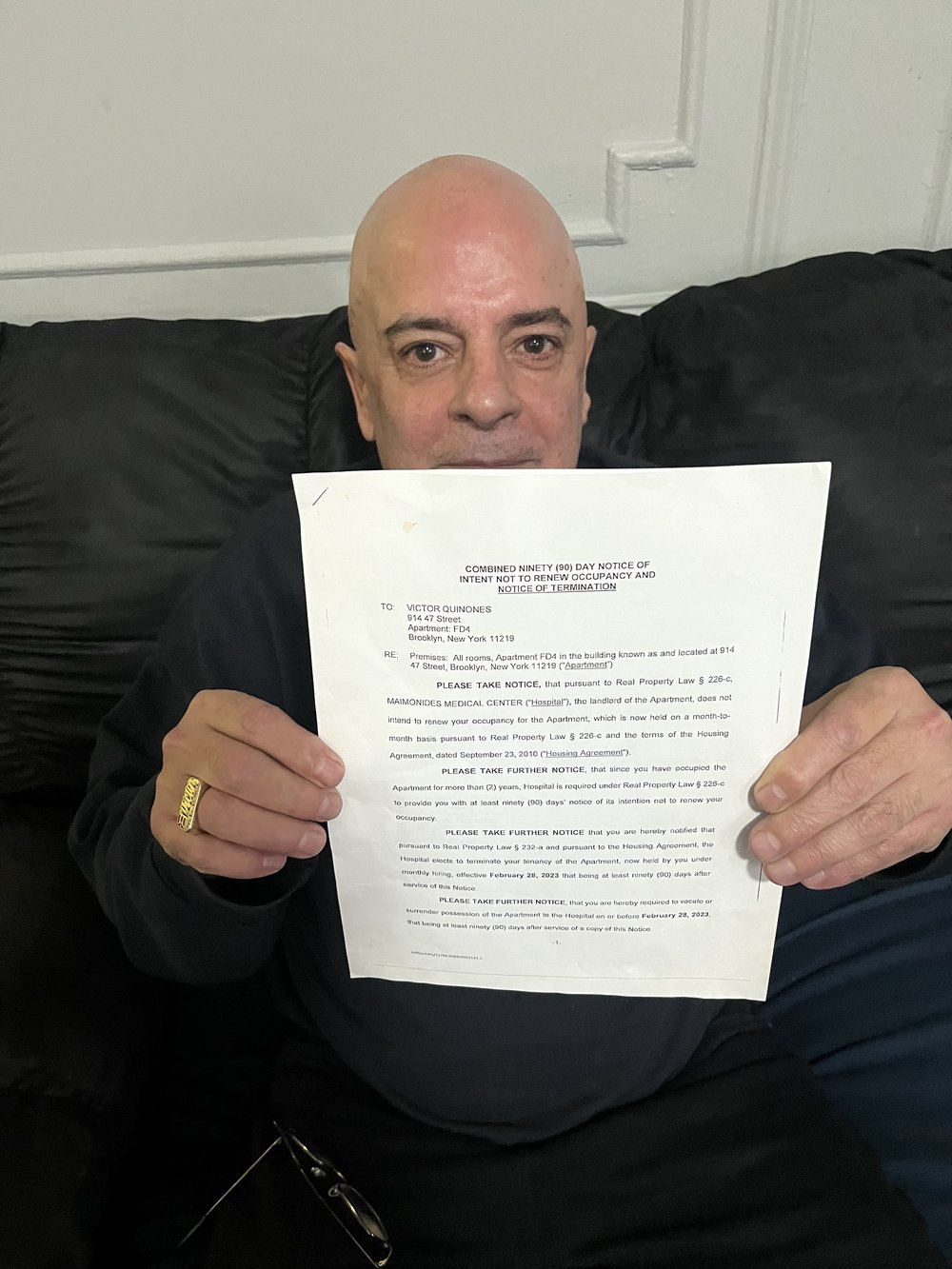

“They didn't give me no paper to sign. They gave me the apartment just like that,” said Victor Quiñones, 66, who said he worked in maintenance for Maimonides for 42 years and moved into employee housing around 2010. He said all he got when he retired in 2018 was a verbal notice that rent for his one-bedroom would increase $300, to $1,250 a month. He said he sent Maimonides rent checks until the hospital stopped accepting them.

In the letters Maimonides sent out in late 2018, informing tenants that the buildings had been sold, the hospital emphasized that tenants were still living there on a month-to-month basis.

Although your right to occupy your apartment ended when your employment at the medical center terminated, the medical center has permitted your continued occupancy at its discretion.

Derek Goins, Maimonides Medical Center senior vice president of real estate and construction, in a letter to tenants

“Although your right to occupy your apartment ended when your employment at the medical center terminated, the medical center has permitted your continued occupancy at its discretion,” Derek Goins, Maimonides’ senior vice president of real estate and construction, wrote in one such letter, which a tenant shared with Gothamist. “Please be advised that pursuant to the terms of your occupancy agreement, the medical center reserves the right to terminate your occupancy at its discretion.”

But Meghan Walsh, a Legal Aid attorney who represents some of the tenants, including Denoon and Quiñones, argued that the nature of the relationship between Maimonides and its employees changed when they stopped working for the hospital, and then changed again when the buildings were sold. Somewhere in there, they should have been offered a lease, she said.

“The majority of these tenants have not worked at the hospital in a very long time,” Walsh said. “There has to be a line at some point. When does this premises become your home and something you have rights to?”

Some tenants have begun requesting their apartments’ rent stabilization histories from the state Department of Homes and Community Renewal and seeking determinations from the agency about whether they should be entitled to rental protections. These requests have had mixed outcomes so far.

In one case, the agency determined that a former Maimonides employee, Snehlata Christian, was entitled to a regulated lease, noting that her apartment had been rent-stabilized before Maimonides purchased the building and made it temporarily exempt from the rent stabilization law in 1987.

The decision withstood an appeal from Maimonides, but the hospital has since succeeded in getting the case reopened and subject to further review.

Tyler Crawford, another Legal Aid attorney working on the eviction proceedings, argued that it’s unfair to bestow some of the benefits of Maimonides’ nonprofit status on the buildings’ new owners by clearing them of their obligations to residents.

Iris Holdings Group agreed in its contract with HPD to reserve a certain number of units in the buildings for people making less than the median household income in the area, which is about $61,000 in Borough Park — and to set aside some of the apartments for New Yorkers who are homeless.

Iris is also required under the agreement to offer a lease to any tenant already living in the buildings, regardless of income – except for those paying rent to Maimonides.

The 2018 master lease, by contrast, indicated that Maimonides tenants were supposed to have a “right of first offer” for vacant apartments. Yet those who spoke with Gothamist said the new owners never offered a lease or contacted them at all.

Iris Holdings Group did not answer questions about what, if anything, the company has done to help Maimondes tenants get leases in the buildings.

Tammaro, the Maimonides spokesperson, said the right of first offer only applied to people who moved out within the first two years of the master lease, even though the tenants had been given more time.

Walsh acknowledged that the Maimonides tenants were able to pay below-market rent for a long time and therefore benefited from their arrangement with the hospital.

“But now, I think what we're seeing is everyone – the city and the hospital and this new landlord – throwing these longtime [tenants] to the wind,” she added.

What will they do next?

Tenants being evicted from these buildings can still apply for the new apartments opening up. But the rents are high compared to what they’ve been paying, and some are taken aback by the realities of the current rental market. Fowler of HPD emphasized that some tenants who move into the new apartments may qualify for housing vouchers or other subsidies.

A two-bedroom at 983 46th St. is listed at $2,731. That’s more than twice the most recent rent Maimonides charged former employee Jorge Santos and his wife Shanti, who have lived in a two-bedroom in that building with their son for 22 years.

The family’s rent reached $1,350 only after the post-sale rent hikes that led up to the eviction filing against them, Shanti said.

Jorge said in Spanish that he was a maintenance worker at Maimonides for 13 years, until he lost his eyesight to glaucoma a decade ago. He learned to navigate his surroundings without being able to see, which is a big part of why they want to stay.

“He understands the building in and out, so it's pretty much easy for him to live in this environment,” Shanti said, adding that they also want to stay close to Jorge’s 90-year-old sister, who lives nearby.

Shanti, a medical assistant, is the only one in the household who’s employed and teared up talking about the toll the situation was taking on her. She said she is hunting for another apartment in the neighborhood, but $2,700 a month is on the lower end of what she can find.

Conrad Ramkissoon, one of Denoon’s neighbors at 1016 50th St., said he is terrified of being put out on the street. Speaking in a measured whisper in Denoon’s apartment on a recent Monday afternoon, Ramkissoon shared the details of being beaten “unconscious” by a patient while working as a nurse in a psychiatric unit at Maimonides in 2010.

The hospital then fired Ramkissoon amid an extended leave of absence the following year, noting that he could no longer perform the duties of his job given his injuries, according to a letter he received from human resources at the time, which he shared with Gothamist.

Medical records Ramkissoon shared say that the attack left him with head, neck and back injuries, which he said continue to cause him severe pain today. Letters from psychiatrists indicated that he still struggles with post-traumatic stress connected to the assault. He said he has been unable to work ever since.

When Maimonides sold the buildings in 2018 but continued to demand rent, Ramkissoon said he found the situation sketchy and began depositing the monthly fees he would have paid the hospital into an escrow account. But he said he had to dip into those funds when there was a disruption in his Worker’s Comp benefits.

“I had no money to live and no money to pay for food, and so I had to take that out. It looks how it looks,” Ramkissoon said. His eviction filing says he owes nearly $60,000 in back rent.

Ramkissoon said he believes he would qualify for rental assistance from the city government if he was able to get a formal lease in the building. And he’s willing to fight for it.

“There are so many things I forgave [Maimonides for], and I try to live by those 10 commandments and just let it fall under the bridge,” Ramkissoon said. “Now this – I can't let them make me homeless. I can't. So this is why I'm going to court.”

Patients were injured, died under care of NY doctor. He moved to New Mexico and kept practicing.