Lawsuit alleges lifetime jury ban harms Black New Yorkers and undermines democracy

Dec. 8, 2022, 6:01 a.m.

The NYCLU filed the federal lawsuit seeking to block the ban in Manhattan.

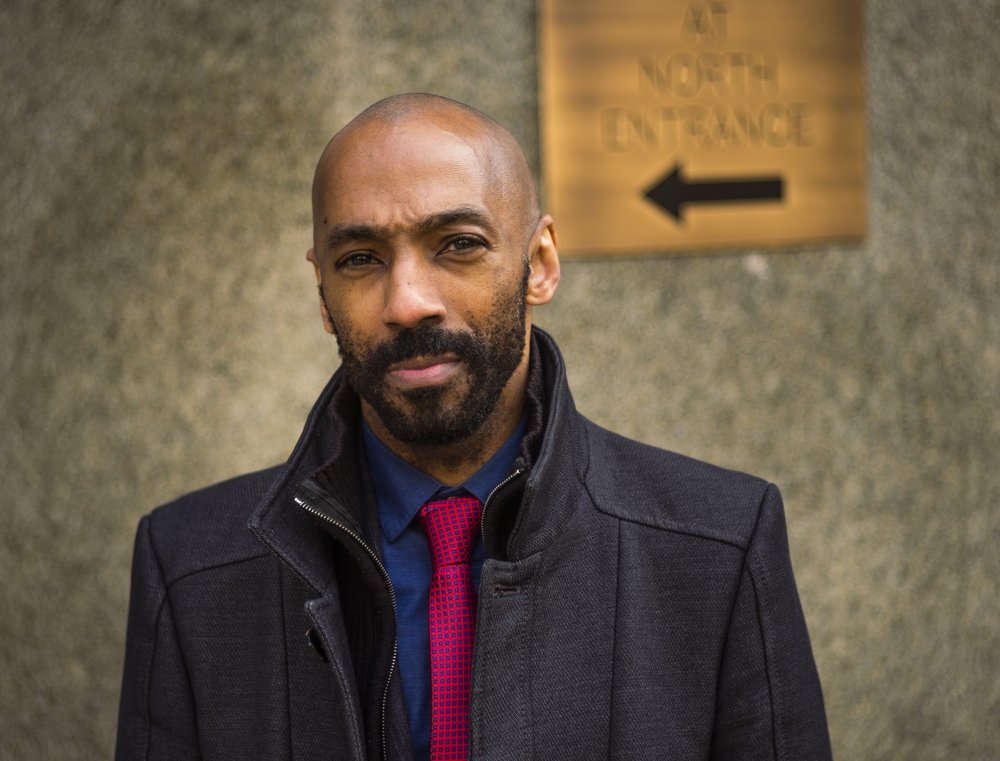

Public defender Daudi Justin is inside Manhattan Criminal Court at least a dozen times each month representing clients faced with misdemeanor charges. On a recent Wednesday, he got two cases dismissed — bringing closure and a measure of relief to his clients.

But one thing the 44-year-old cannot do inside the courtroom is serve on a jury. Justin was convicted of a felony when he was 31 years old, and under current New York state law, he is barred from jury service.

Hear WNYC senior politics reporter Brigid Bergin's story outlining the details of the NYCLU's lawsuit:

That exclusion is the focus of a federal class action lawsuit filed Thursday by the New York Civil Liberties Union. It seeks to toss out a law the group says leads to the “mass disenfranchisement” of Black citizens in Manhattan, including Justin, who is Black. The suit goes on to say such a law “dilutes the voting strength of Black citizens on juries, an institution that is fundamental to democratic self-government and the administration of justice.”

The decades-old law sought to ensure the integrity of juries. But since it imposes a lifetime ban on jury service, people who were convicted of crimes that are no longer considered felonies continue to suffer a consequence. This is referred to by legal experts as “civil death,” which describes the elimination of civil rights as an added punishment on top of the conviction.

The suit also argues that the law fundamentally undermines democracy by limiting participation and “perpetuates a vicious cycle” where Black people are underrepresented on Manhattan juries and overrepresented among people with felony convictions.

Justin and the Community Service Society of New York, a nonprofit that works on equity issues, are the named plaintiffs.

Jury service matters because everyone has a right to participate in a democracy. And I think every defendant has a right to have the members of his peers in the jury system, even if that includes people who are convicted of felonies.

Daudi Justin, public defender

The defendant is Milton Adair Tingling, the county clerk of New York County and the Commissioner of Jurors, the person who determines if someone qualifies for jury service and sends out the summons. Tingling, who served as a state Supreme Court justice in Manhattan for more than a decade, was the first Black county clerk in New York state history. He’s also made no secret about his desire for more Black New Yorkers to serve on juries.

How the law plays out

Current state jury eligibility is subject to four specific conditions: a person must be a citizen of the U.S. and a resident of the county that is requesting their service; be 18 years or older; not have been convicted of a felony; and be able to communicate and understand English.

The suit alleges that more than 25% of otherwise eligible Black citizens in Manhattan are excluded from jury service based on the current state law. That means of the 152,000 Black residents in Manhattan who meet all the other legal criteria for jury service, roughly 38,000 are barred due to a felony conviction, according to the complaint. By comparison, of the approximately 900,000 qualifying, non-Black Manhattan residents, only about 28,000 — or about 3% — are excluded as potential jurors because of a felony, the complaint alleges.

[Justin v. Tingling] Compla... by Brigid Bergin

Those estimates are based on an NYCLU analysis of felony conviction data from multiple sources including the state Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS), the Department of Correction and Community Supervision, academic reporting from John Jay College and data from the U.S. Census Bureau. These allegations are likely to be the subject of expert testimony if the lawsuit goes to trial.

The suit argues that vast disparity between prospective Black and non-Black jurors is a product of decades of racialized policing policies and prosecutions that targeted Black communities in Manhattan, including the unconstitutional use of stop-and-frisk and the targeted enforcement of drug laws.

The complaint cites data from the Division of Criminal Justice Services that found over half of all felony drug convictions in New York City came from Manhattan, when data was recorded from 2002-2019, and affected Black defendants at substantially higher rates.

Daudi Justin’s story

For Justin, his entanglement with the criminal justice system began in 2007, when police burst into his Chelsea apartment in the predawn hours with a warrant to search for drugs. He was arrested for possession of crystal meth, and took a felony plea deal in 2009. He served nearly two years in multiple upstate prison facilities.

After he was released, Justin attended the Borough of Manhattan Community College before transferring to Columbia University. It was while he was a student at Columbia that Justin first learned he was excluded from jury duty. He received a summons in the mail requesting his service, but it also indicated that a person with a felony conviction did not qualify — and they needed to produce documentation to prove they didn’t qualify.

“It just sounded so ridiculous,” said Justin. “Like, I don't want to be disqualified for jury service.”

Justin learned that he was excluded from jury duty while a student at Columbia University. After graduating, he attended the CUNY School of Law, graduated in 2021 and gained admission to the New York Bar this past June.

After Columbia, Justin attended the CUNY School of Law, graduated in 2021 and gained admission to the New York Bar this past June. He now makes the case for why people, especially those who have been incarcerated, should be civically engaged to the fullest.

“We bring a different perspective to the system and we bring a different perspective to the [jury] room,” said Justin.

A burdensome solution

Legal scholars have long drawn the line between a functioning democracy and civil rights like the ability to vote and serve on juries. In both instances, people are holding the government accountable.

“The ballot box is what keeps elected officials accountable to the people. The jury box is what keeps the administration of the law accountable to the people,” said Perry Grossman, a supervising attorney for the NYCLU who is representing the plaintiffs in the suit. “These are just different forums for voting.”

New York has taken steps to restore the voting rights of formerly incarcerated individuals. In May 2021, then Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed a bill into law that automatically restored the voting rights of people with felony convictions upon release from prison.

The one way for a person with a felony conviction to restore their right to serve on a jury is to complete a certification process. But experts say it is a cumbersome process that demands persistence, expertise and even knowledge that the option exists in the first place. It’s unclear how long the process can take and there are no clear standards, leaving applicants at the whim of the state.

“It’s not very accessible,” said Paul Keefe, vice president of legal services at the Community Service Society of New York, one of the plaintiffs in the case. His organization is one of five that the state refers people interested in certificates to because of its expertise in the process.

Keefe said people face numerous obstacles just figuring out which certificate process to complete based on the number of felonies a person has, where they were incarcerated, whether they need to submit to an additional waiting period or open their home to an inspection from a state corrections official.

As a result, far fewer people use this option than are eligible. The lawsuit notes that in 2021, the Community Service Society assisted 40 people with the certificate process in all of New York City. In that same year, more than 40 times that amount of people — 1,700 — were convicted of felonies in Manhattan, according to data from DCJS.

Justin considered applying for a certificate to restore his right to serve on a jury. But he ultimately decided against it after learning about the steps required. After spending nearly two years in prison, he said it scared him to think about a parole officer investigating him.

“It's not something that anyone who's been incarcerated wants to have to go through,” he said.

A climate ripe for change

State lawmakers have considered legislation to end the lifetime ban for people with felony convictions from jury service. State Sen. Cordell Cleare of Harlem and Assemblymember Jeffrion Aubry of Queens carried the bills in the last session. That legislation is expected to be introduced again in January, according to staff in Cleare’s office.

Public statements from Manhattan’s top prosecutor and Tingling, the defendant in his current capacity as county clerk, also signal an openness to examining this issue.

In an interview with Gothamist last week, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg called jury service “a core part of our democracy.” Asked whether he would support overturning the current law that bars people with felony convictions from jury service, he did not rule it out but said he would need to think about it on a case-by-case basis.

“I think we're moving towards more of a blanket, let's figure it out using the voir dire process,” said Bragg, referring to the process by which a judge and attorneys question potential jurors about their ability to be fair and impartial. “That general principle is something I am certainly on board with,” he said.

While Tingling has not yet responded to a request for comment, he has made previous statements that suggest he supports changes to the law that would allow more Black citizens to serve on juries in Manhattan.

“People of all colors have petitioned, protested, marched, sat in, fought and died for the opportunity and right of people of color to serve on juries and make decisions as jurors who happen to be people of color,” he wrote in an op-ed for the New York Amsterdam News, headlined, “Jury Service is a right and privilege.”

He added, “jury service is a duty. It is a right. It is a privilege. Quite frankly, for communities of color it has to be an obligation.”

In a 2015 interview with the same publication when he was made county clerk, the paper described Tingling as an outspoken champion of voter registration and jury service, particularly among communities of color, calling it “his passion.”

“American citizens have so many privileges,” Tingling told the paper, “and the country only asks you to do two things: vote and do jury duty.”

A spokesperson for the Office of Court Administration (OCA) said the NYCLU was taking issue with a statute passed by the state Legislature that lays out the qualifications for jurors.

“Until such time as the Legislature changes the law or a court of competent jurisdiction declares it invalid, Commissioners of Jurors are sworn to enforce these qualifications,” said Lucian Chalfen, the OCA spokesperson.

His comment came in direct response to a letter the NYCLU sent to Tingling three months ago laying out their concerns. That letter was referred to the counsel at OCA and warned of an imminent lawsuit.

A matter of perspective

On Thursday, Justin is expected to be back at Manhattan Criminal Court defending his clients. He has more than a dozen cases scheduled for the day. With fewer Black jurors in the pool, Justin charges that a lack of diversity can affect the outcome of a case. More than anything, he wishes people would not take the experience of serving on a jury for granted.

“We need this diversity of opinions because that one single fact could change the outcome of a case…we’re denying individuals that opportunity to have a different perspective,” said Justin.

A few weeks back, Justin joined a colleague in the voir dire room as potential jurors were being selected. He knows most people aren’t thrilled when they receive a jury summons, but one thought kept running through his mind.

“These jurors have no idea how lucky they are,” said Justin.

The story has been updated to reflect that the NYCLU's lawsuit against the state was filed Thursday morning. It’s also been updated to include comment from the Office of Court Administration.