Judge Orders Greater Access To Medical Care At Rikers Island

Dec. 6, 2021, 5:37 p.m.

Detainees held in the city’s troubled jail system have continued to miss medical appointments as hundreds of jail guards call out sick or miss work.

Judge Elizabeth A. Taylor has ordered the New York City Department of Correction to give people incarcerated in city jails greater access to medical care. In a court decision filed Monday, the Bronx judge held that city jails must ensure detainees can go to on-site clinics at least five days a week and within 24 hours after a visit request. The judge also mandated that corrections authorities guarantee enough security staff to shepherd them to and from medical visits.

The order comes in response to a court petition from a group of public defenders and attorneys who are seeking better conditions for clients who have routinely missed medical appointments as hundreds of jail guards continue to call out sick or skip work.

“After this tragic year, when at least fourteen New Yorkers have died at Rikers Island and other local jails, we are grateful the Court took swift action to order the DOC to fulfill its obligation to provide the thousands of New Yorkers who remain in the jails with access to medical care,” said Veronica Vela, supervising attorney with the Prisoners’ Rights Project at The Legal Aid Society, one of the groups behind the court petition.

In a statement, a Department of Correction spokesperson said the agency “completely” agrees that “health care is a human right” and that it does its best to ensure that right is fulfilled. “While COVID and related staffing issues have challenged us, we are determined to deliver services to those in our care to the best of our ability,” the agency said.

According to the latest publicly available data, between July and September of this year, jail health authorities recorded more than 18,000 instances in which incarcerated people were not produced for scheduled services. The Department of Correction claims that in many cases detainees “refuse” to attend medical visits. But advocates counter that the agency’s inability to get staff to come to work has caused routine service breakdowns.

“Every day we hear from people in distress, in need of both emergency and routine medical care, and yet these calls for help regularly go unanswered,” said Brooke Menschel, director of Civil Rights and Law Reform at Brooklyn Defender Services. “The results are devastation, suffering, and death.”

Several detainee deaths in city jails have been due to “natural causes.” Some families and advocates believe the jail system’s inability to provide prompt and adequate medical care in crowded settings has contributed to these deaths.

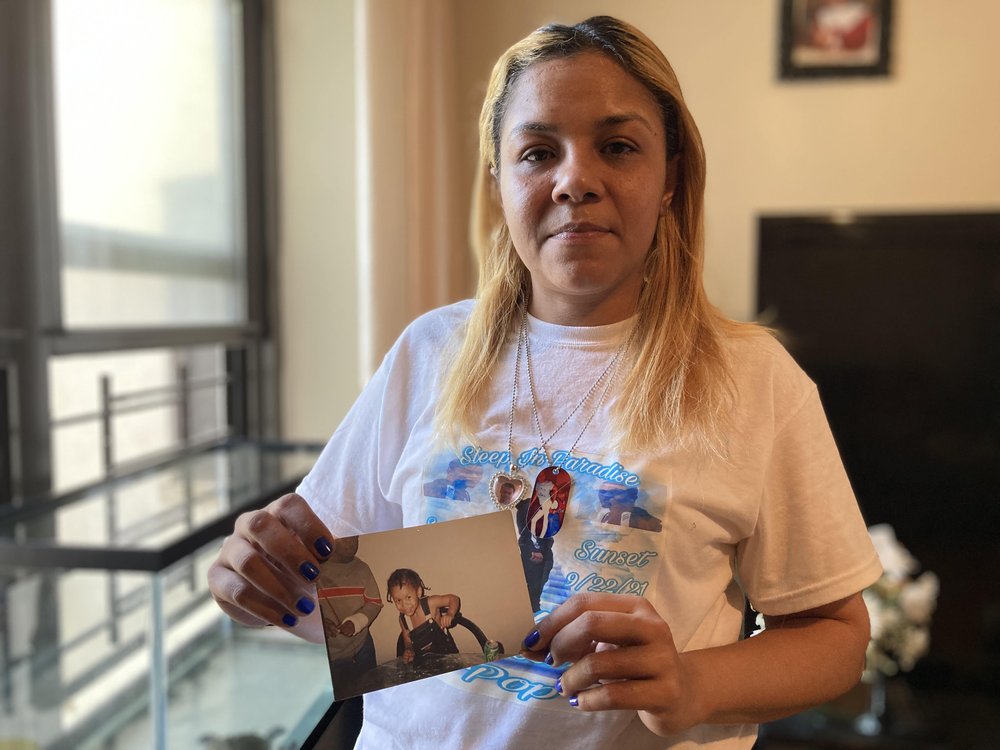

In September, 24-year-old Stephan Khadu died at Lincoln Hospital after being transferred from the Vernon C. Bain Center, a floating jail barge in the Bronx near Rikers Island. Khadu’s family believes his death stemmed from seizures he began suffering from while incarcerated over the summer. The family blames jail conditions for his deterioration in health. Lezandre Khadu, Khadu’s mother, claims that even after he was hospitalized after having convulsions in July, jail authorities returned him to his cell, rather than to an infirmary where he could be regularly monitored.

“Why would y'all put him back in this same cell? There's no air, there's no ventilation,” she said.

The Department of Correction declined to comment on the case, which is currently the subject of a lawsuit.

A few days before Khadu’s death, Isaabdul Karim, 42, died after telling authorities he wasn’t feeling well. His attorneys say he had previously contracted COVID-19 while waiting in a jail intake area for ten days, though his exact cause of death is unknown.

In October, Victor Mercado, 64, died at Elmhurst Hospital after contracting COVID-19 on Rikers Island, according to his attorney.

“If DOC is still unable to comply with this ruling, it has no authority to detain, and the City and State must act immediately to release people in its custody to prevent further suffering,” Vela said.

A spokesperson for the Correctional Health Services, the agency in charge of medical care in city jails, declined to comment for this story.

This article has been corrected to accurately reflect Mr. Khadu's age at the time of his death. He was 24 years old, not 34 as originally stated.