‘It’s like a public dump.’ How the remains of formerly enslaved people came to rest beneath a Staten Island strip mall

Feb. 9, 2023, 12:28 p.m.

Benjamin Prine's descendants didn’t know about their family ties – or their connection to his enslaver.

Ruth Ann Hills, left, and her brother David Thomas.

For most of her 74 years, Ruth Ann Hills took a certain innocent pride in her family’s story and its place in Staten Island history.

Generations of her family had resided in Mariners Harbor on the island’s North Shore. She and her brother David Thomas live in the house their grandfather built on Van Pelt Avenue. They had found Black ancestors on Staten Island as far back as the 1700s, and incredibly they had all eluded slavery.

Or so Hills thought.

All of that changed one day in 2021, when Hills received a visit from a filmmaker. Heather Quinlan was working on a documentary about a nearby graveyard. Over the course of her genealogical research, Quinlan had discovered that one of the people buried there was Hills’ great-great-great-grandfather.

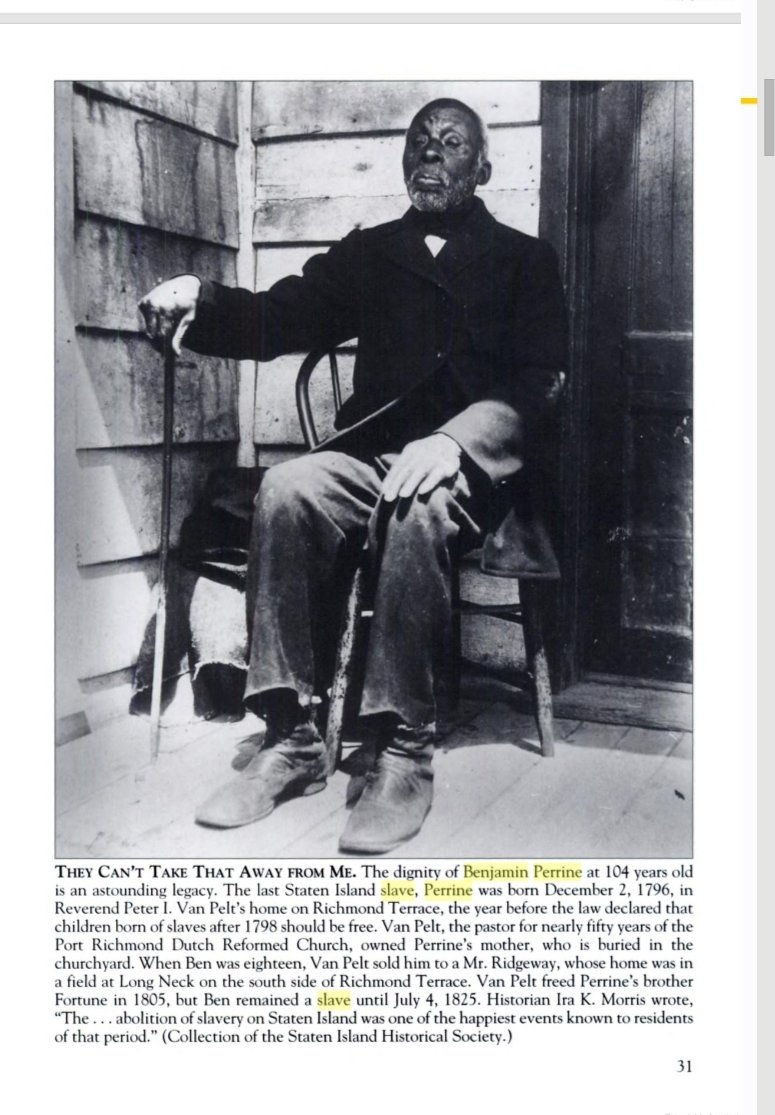

Neither Hills nor Thomas had ever heard of the man, Benjamin Prine, but his death in 1900 at the age of 106 had been covered by the New York Times and the wire services. Prine, a U.S. veteran of the War of 1812, had been the last enslaved person born on Staten Island, Quinlan told them.

Hills' and Thomas' great-great-great-grandfather, Benjamin Prine.

Prine had once been enslaved by Peter Van Pelt, a highly influential Dutch Reformed Church minister – meaning that the street on which the siblings now live took its name from the same white family that enslaved their ancestor.

“I thought I was a big history buff. ‘Oh, I know about history,’” Hills said. “I guess I was naive.”

Most disturbing to Hills and her brother was the revelation about Prine’s final resting place. From the 19th century until the mid-20th century, the site had various names: the Colored Burial Ground, the African Burial Ground or Cherry Lane Cemetery. Today, it is a strip mall. All signs of Prine and others who remain interred at the cemetery – anywhere from 90 to 1,000 people – have been obliterated.

“Every day, for years and years and years and years, they were just walked over and desecrated,” said Thomas, 65. “And that's just a sin to me. That's shameful.”

That could be about to change, at least in some way.

In the past year, the siblings, along with Quinlan and a growing network of activists, historians and elected officials, have come together to demand public recognition of the site. They want to educate the public about what happened at Cherry Lane Cemetery, through a commemorative plaque, historical signage and perhaps a garden.

Recently, at the urging of Councilmember Kamillah Hanks, a City Council committee agreed to co-name Livermore Avenue, which runs alongside the cemetery, “Benjamin Prine Way.”

For Thomas and Hills, that was merely a starting point. As Prine’s descendants, they feel that the violation of their ancestor’s body is so great that it requires more than symbolic measures. They want financial compensation and for the bodies to be moved elsewhere. At the same time, they recognize that doing so could prompt opposition and a backlash.

“You right that wrong, no matter what it takes,” said Thomas. “That's what we want.”

The concern is not theirs alone. Historians say there are sites like Cherry Lane across the city – across the country and the colonized world, in fact — that serve as earthly reminders of what African Americans have endured and overcome. A number of Black activists and historians say the path forward involves bringing dignity to the ancestors and undoing centuries of systemic erasure.

“Now there's this movement to reclaim the humanity and rebuild the communities that were lost to history,” said Peggy King Jorde, who has overseen the preservation of Black burial sites across the country.

The life and disappearance of Cherry Lane Cemetery

The story of Cherry Lane Cemetery and the people buried there is complicated. A litany of competing facts makes it difficult to determine the truth of who was buried there, who oversaw the site, and how it became the home of a 7-Eleven and a Santander Bank, among other businesses.

But Quinlan has been trying. Her documentary in progress is called “Staten Island Graveyard.”

On a recent day she stood before the strip mall that now concealed the burial ground. In the parking lot sat a refuse container, surrounded by a chain-link fence. Garbage was scattered across the ground, including a discarded tub of Philadelphia cream cheese and an empty box of Marlboros. It was clear that people had defecated here as well.

“I believe there are remains under here,” Quinlan said. “Usually there's people either dumpster diving or urinating or treating it as their own personal trash bin.”

Quinlan, a Staten Island native, was first alerted to Cherry Lane Cemetery around eight years ago, while reading “Graveyard Shift: A Family Historian's Guide to New York City Cemeteries,” by Carolee Inskeep.

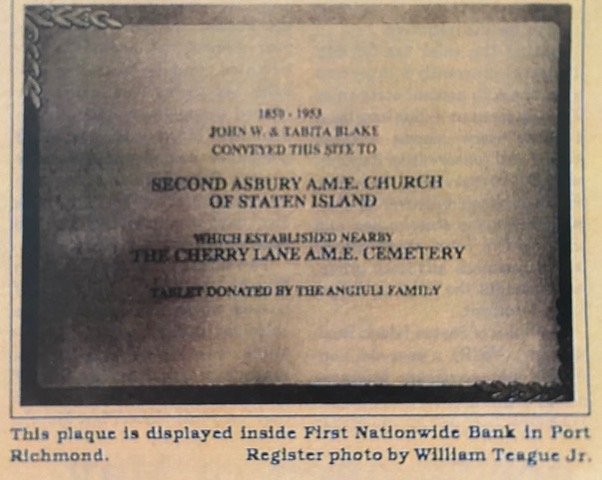

Inskeep wrote that the cemetery had been established in 1850 after John W. Blake deeded the property to the Second Asbury African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1889, historian William Thompson Davis visited the site, according to Inskeep, and noted “that the church building had been pulled down and used for fencing.”

“He also observed that the majority of the graves in the yard had been marked with wooden stakes and mounds of dirt,” wrote Inskeep, adding that Davis found just two gravestones. “The first was a broken marble slab dedicated to the memory of Augustin Jones, who died Feb. 18, 1873 at the age of 33. The second was a white wooden board, neatly lettered in black, to the memory of Aaron Bush,” who died in 1889 at the age of 46.

Davis had served as president of the Staten Island Historical Society and authored a number of books in his capacity as both a historian and an entomologist.

In “Staten Island and Its People: A History, 1609-1929,” a five-volume work he co-authored with Charles W. Leng, Davis noted that the Second Asbury African Methodist Episcopal Church became the Zion African Methodist Church in 1854 and the property came into the hands of Francis De Hart.

“This property was on Cherry Lane (now Forest Avenue) west of Jewett Avenue, and opposite the dye works, locally known as the ‘Colonel’s Factory.’ We can remember 40 years ago the graves that were there, many of them unmarked.”

Debbie-Ann Paige, the co-president of the Staten Island Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, said other historians had also documented the cemetery's existence.

“We are not the first to discover this story,” Paige said. “And so we are now ‘discovering’ this story that's so important for all of us to know.”

Noted Black historians like Evelyn King Morris and Richard Dickenson were well aware of the site and had tried to alert the public about it.

Paige scanned her bookshelves and pulled out a volume riddled with Post-it notes. It was “Holden’s Staten Island: The History of Richmond County,” edited by Dickenson, who for years served as the borough’s official historian.

“He has been telling this story for a long time, but people weren't listening,” Paige said.

In 1915, his book notes, Charles A. Mulligan, deputy tax commissioner for the 1st District, had filed a report.

“I have examined the premises,” wrote Mulligan, “and find no outward evidence of there being a cemetery; no mound or headstones, and the plot not fenced.”

However, Mulligan also said he’d interviewed 10 people, including four locals, and that it had been “about 20 years since the last interment.”

“It was also stated that the plot is entirely filled with bodies, graves having been open promiscuously without regard to space.”

These competing impressions – the evidence of bodies, along with official professions of “no outward evidence” of a cemetery – were part of a pattern that played out in the 20th century.

In the early 1900s there were no more burials taking place at the cemetery. By this point the church had been vandalized and torn down, Quinlan said, and the congregation had moved elsewhere. A board of trustees was appointed to oversee the cemetery but failed to file the appropriate paperwork to exempt the site from taxes.

In 1954, said Quinlan, the city sued the board for $11,000 in unpaid taxes.

“It might as well have been $11 million,” Quinlan said. “There was no way they could pay that amount of money.”

So the site was auctioned. The new owner built a Shell gas station on the property.

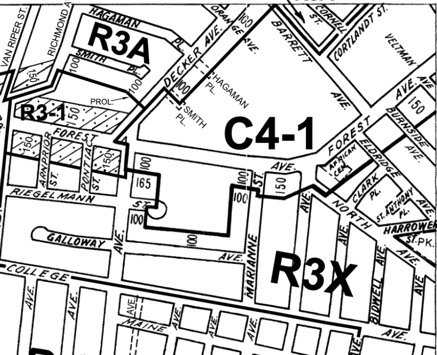

For decades, articles and maps clearly identified a cemetery at the location. An “African Cem” was marked on a New York City Planning Commission map as recently as 2018, decades after the site had disappeared.

“I thought, this is a horror movie,” Quinlan said. “And there is no one to give voice to them because they're buried under asphalt.”

Paige said the site's development was a form of theft that she’d encountered in other instances on Staten Island. In one, a Black family in the 1940s was blocked from selling their house because they were told their ancestor had been a fugitive and had thus illegally obtained the deed to the property a century earlier. Paige’s research revealed that the ancestor had been enslaved in Virginia but that his wife had purchased his freedom before they moved to Staten Island, meaning that the house had been legally obtained.

In another instance, Paige said, a white real estate agent had offered to help her obtain archival records as a form of “atonement,” acknowledging that his father had cheated Black families on Staten Island out of their homes decades earlier.

Given that history, she said it wasn’t hard to see how the cemetery on Cherry Lane “could easily fall into the hands of someone else.”

How the past informs the present

For some Black community advocates on Staten Island, the erasure of Black history at the cemetery dovetails with a larger problem: Many New Yorkers don’t think of Staten Island as a place that contains Black history. While 23% of the city’s population is Black, the proportion is half as much on Staten Island.

“When I go off to Manhattan and I say, ‘I'm from Staten Island,’ they go ‘Staten Island? Are there Black folks there?’” said Bobby Digi Olisa, the executive director of Canvas Institute, an arts and culture space.

He said the revelations about the cemetery were like “a smack in the face.”

“There's so much injustice here, and it creates an opportunity to right that wrong,” he said.

For Paige, the local historian, the general absence of markers affected her as a child who was raised in the borough.

“My entire life growing up, I kept looking for myself in the history,” Paige said. “I was looking for myself in the streets, in the street naming, in the pictures, in my school books, and those things weren't there. The students, the children today, are still looking for themselves in the histories.”

Staten Island's history was one of racial conservatism, including during the Civil War. While most of New York City was pro-Union, Staten Island was overwhelmingly supportive of the South and the enslavers who lived there, Paige said.

Bracing for a backlash

As the sole descendants currently involved in the cemetery project, the voices of Thomas and Hills appear to carry some weight, but it remains to be seen how much buy-in the siblings will get as the project unfolds.

They say they’re gratified by the responsiveness of officials at Santander Bank, among the commercial tenants doing business on the property. It has agreed to mount a plaque on the building’s exterior, with language from Thomas and Hills that proclaims, “This plaque is dedicated to those souls, their descendants, and all who seek to remember them, with love and dignity.”

Santander officials also took part in an October press conference announcing that a memorial would be built on the site. The bank has also pledged to plant a $4,000 cherry tree, a nod to the history of Cherry Lane Cemetery.

“We’ve been on an ongoing journey to learn, and to ensure we do what’s right with getting the land memorialized,” said Yajaira Lopez, an executive vice president and region president at Santander, in an interview with Gothamist. The bank noted it has been working with "the property owner, landscape architects, the City's Parks & Recreation department and various other stakeholders to make this memorial a reality."

Lopez said the bank had not yet considered a more ambitious demand from Thomas and Hills: The siblings want all the bodies to be exhumed and reburied in a proper cemetery so they can pay their respects.

Hills also wants some financial compensation.

“I come from something, and my grandfather, great-great-grandfather was a slave,” one who had fought against the British, she noted. “Yeah, I think that I should have some kind of reparation. I'm not talking about millions of dollars, but something for my family. That's it.”

Ed Josey, the president of the Staten Island chapter of the NAACP, also believes in re-interring remains, but worries about the impact on local businesses.

“I would like to see it be done, but now how do you get around pacifying these businesses there?” Josey said. “I mean, they're gonna resent that because they’re going to be out of business for a while.”

A growing team

In any case, the effort is growing in size and ambition. The expanding team of activists, officials and consultants joining the effort now includes Peggy King Jorde, who comes with an illustrious civil rights pedigree. Her father, C.B. King, was an attorney who represented Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy and John Lewis.

Jorde herself served under three New York City mayors and led the effort to build the African Burial Ground in Lower Manhattan, a national monument that marks the resting place of 15,000 free and enslaved Africans dating from the colonial era.

Since then, she has worked on similar projects in Georgia and Virginia as well as St. Helena and Sint Eustatius, islands in the British and Dutch Caribbean. Locally, Jorde said there are numerous burial grounds containing the remains of people enslaved by the city’s founders, such as Jan Dyckman and Jan Nagle.

“It was normal for this country to cover up these sites,” she said, “because these were communities who were considered ‘other,’ they were not part of America. They were considered subhuman.”

In Brooklyn, activists are fighting to preserve the Flatbush African Burial Ground, located at 2286 Church Ave., and were heartened when a proposal supported by former Mayor Bill de Blasio to build affordable housing on the site was blocked. It now appears increasingly likely that the space will become an open memorial, a plan Mayor Eric Adams backed during his election campaign.

Allyson Martinez, who helps lead the Flatbush African Burial Ground Coalition, said she was “cautiously optimistic” about progress at the site. She said that the area's Black population had declined and that those who remained would benefit tremendously from a space that acknowledged their history.

“We're living in a community that's facing cultural erasure due to gentrification,” Martinez said.

Martinez said it isn’t clear how many people were buried at the Flatbush African Burial Ground. Jorde said the number is not that important. What matters, she said, is what transpired there.

“Anthropologists or archeologists say that what in part defines us as human is how we bury our dead,” Jorde said. For enslaved people, the act of burial serves an additional purpose.

“The community in that fact is reclaiming the humanity of that individual – of that brother, that sister, that mother, that father in that moment,” Jorde said, “and in that moment if you can imagine doing that, where there are laws that treat you as subhuman or define you as subhuman, what you are engaging in is a revolutionary act.”

And in this process, she said, the ground became sacred. And for this reason, it was critical to preserve both the memories and the sanctity of the sites for generations to come.

“How do we tell that story?” Jorde asked. “How do we make it live on within our community?”

This article was updated: It included additional comment from Santander Bank, among the commercial tenants doing business on the property. It also corrects the attribution of two statements incorrectly attributed to Allyson Martinez, who leads the Flatbush African Burial Ground Coalition.