Is Vision Zero a success for New York City?

Jan. 19, 2024, 3:30 p.m.

From our transit newsletter: Evaluating Vision Zero after a decade, a reader question about connecting train stations and a roundup of this week’s transit news.

This column originally appeared in On The Way, a weekly newsletter covering everything you need to know about NYC-area transportation. Sign up to get the full version in your inbox every Thursday.

This week marks the 10th anniversary of New York City’s Vision Zero program. The initiative aims to eliminate traffic deaths through better road design for pedestrians and cyclists, as well as an aggressive crackdown on reckless drivers.

Sweden was first to launch a version of the program in the late 1990s. Following New York’s lead, cities across the U.S. have embraced the push for street safety.

Now, with a decade of experience, New Yorkers are reflecting on the effectiveness of the policy. This week, Gothamist and WNYC looked back at Vision Zero and concluded the program was indisputably a success — at least in areas where it won the support of elected officials.

Here’s former Mayor Bill de Blasio explaining his thinking on Vision Zero during a recent interview with “Morning Edition” host Michael Hill.

“The more I understood it, the more I said, you know, if we're going to fight murder, if we're going to devote massive resources to protecting people from being shot and killed, why are we not making a similar effort to protect people?” de Blasio said.

The city Department of Transportation is quick to note the number of people killed in car crashes has reached historic lows since Vision Zero launched in 2014. The agency shared data all the way back to 1910, which shows the city’s eight best years for street safety have all come in the past decade.

That’s marked progress from the 1990s, when the city recorded no fewer than 368 traffic deaths every year. And it’s a dramatic drop from the late 1920s and early 1930s, when motorists killed more than 1,000 people a year.

But at the same time, street safety advocates have plenty of reasons to demand the city recommit itself to Vision Zero.

The city has seen increases in yearly traffic deaths since recording an all-time low of 206 in 2018. Last year, the number reached 257. The rise comes as Mayor Eric Adams has come under criticism for walking back street safety projects across the five boroughs.

De Blasio, who launched Vision Zero during his first year in office, faced similar scrutiny for slow-walking some of his administration’s own street safety initiatives. In summer 2019, as the city saw a surge of cyclist deaths, advocates blamed his administration for failing to add enough new bike lanes across the five boroughs.

Vision Zero has coincided with a cycling boom. The number of people riding bikes in New York reached an all-time high in 2023 – the same year 29 cyclists died in traffic. That’s the highest toll since 1999, when 35 cyclists were killed.

Among those killed were e-bike riders and app-based delivery workers; neither group was such a common sight on the roads when Vision Zero launched. Of the 29 cyclists killed last year, 22 were riding e-bikes.

The e-bike crashes indicate an ongoing problem that will likely dominate Vision Zero conversations in the coming years.

“The way that this street is being used now has changed and it's gotten ahead of our street design," former city Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan told WNYC this week. Electric mobility is moving faster than bikes and faster than transit and faster than regulators. So, we're sort of seeing next-generation problems but we're not seeing next-generation solutions and new mobility lanes at the scale and design that's needed.”

This week's NYC transit news

- To revamp the signal operating system, the MTA wants to instate three major shutdowns of the G train from June through Labor Day. Read more.

- Since the launch of Vision Zero, Queens Boulevard, AKA the Boulevard of Death, has gotten much safer. Atlantic Avenue, AKA the new Boulevard of Death, has not. Read more.

- A Brooklyn mother and leading Vision Zero advocate whose 12-year-old son was fatally hit by a truck driver in 2013 is still pushing state lawmakers to pass "Sammy's Law," which would allow New York City to set its own speed limits. Read more.

- The FDNY responded to 267 fires caused by faulty e-bike batteries in 2023 — about 20% more than in 2022 — even as lawmakers have tried purging the market of low-quality batteries. Read more.

- New York City is testing new technology that automatically prevents school bus drivers from speeding. Read more.

- A teenage boy died after surfing atop an F train on elevated tracks in Brooklyn last Friday, with witnesses saying he fell off the train all the way to the street. Read more.

- Amtrak on Thursday canceled more than a dozen trains along its Northeast Corridor due to freezing temperatures. Read more.

- In other Amtrak news, the new (overdue) Acela trains passed a crucial computer modeling test (on the 14th try), meaning the trains are now ready for test runs on actual tracks. (The New York Times)

- The MTA said it's tweaking the locks on subway conductor cabs to keep people from breaking in and taking trains for joyrides, among other misdeeds. (THE CITY)

- Plainclothes NYPD teams are still out in the subway system busting alleged fare evaders and people drinking on platforms. (amNewYork)

Anchor Tag

Curious Commuter

Question:

Why is there no subway transfer between the Lorimer Street J and M station and the Broadway G station?

– Dennis, from Brooklyn

Answer:

There are a few places in the city where subway lines overlap without offering riders a free transfer, but the point in South Williamsburg where the elevated Lorimer Street station and underground Broadway station cross paths is among the most egregious.

The layout of the stations isn’t dissimilar to the Franklin Avenue shuttle and the C line, which overlap in Brooklyn at Fulton Street and allow riders to transfer without crossing through the turnstiles. But the MTA has no plans to build a similar connection between Lorimer Street and Broadway.

The MTA did, for a while, offer free transfers between the stations when the agency performed construction on the L train’s East River tunnel in April 2019. The work hampered service on the L line during nights and weekends for a year — so the agency temporarily offered riders a free entry into either station if they’d recently swiped or tapped into another subway stop. The MTA ended the free transfer in June 2020, saying it was only offered as part of the L train construction plan.

Have a question? Follow @Gothamist on Instagram for special opportunities and prompts to submit questions.

You can also email cguse@wnyc.org or snessen@wnyc.org with the subject line "Curious Commuter question."

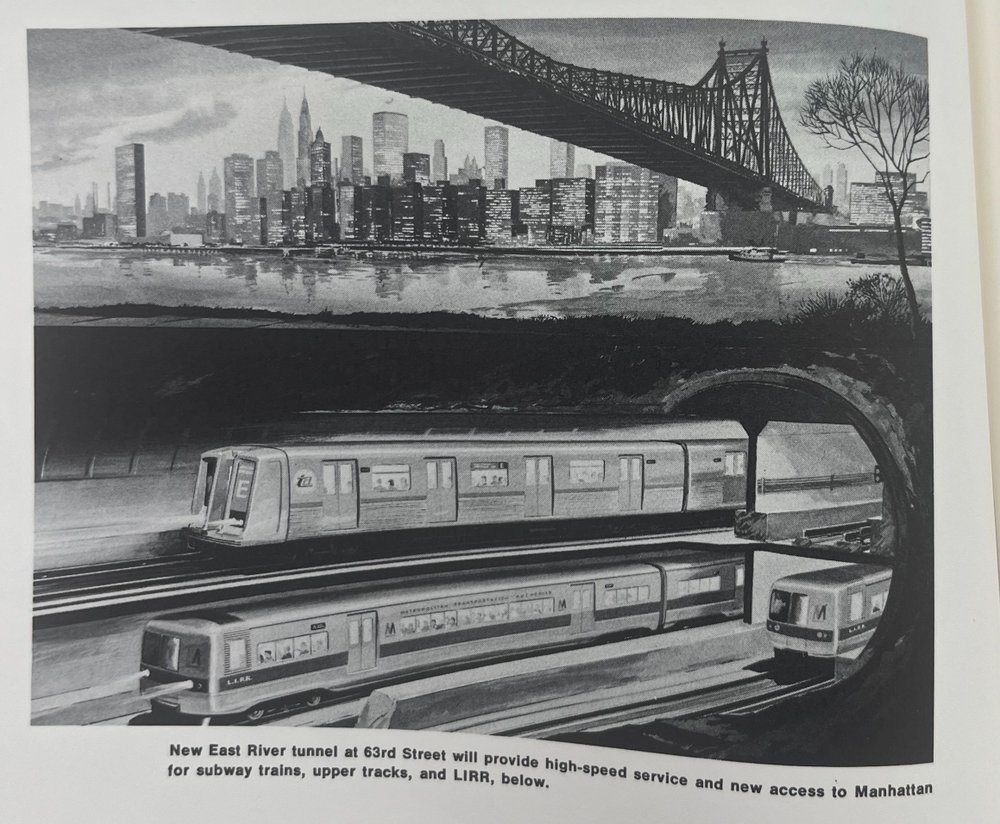

From the archives: This week in transit history

When the MTA launched in March 1968, its top brass promised to build a double decker train tunnel under the East River stretching from East 63rd Street in Manhattan to Vernon Boulevard in Long Island City. The tube was to carry subway trains on its top level and LIRR trains on the bottom. The MTA initially planned to dig out the tunnel from underneath the river, as was the case with the rest of the East River subway crossings. But the initial proposals for the work came back far over budget, so transit planners went back to the drawing board.

Instead of boring beneath the river, the MTA decided to dig trenches in the channels on either side of Roosevelt Island, then bury prefabricated tubes. The dredging work to dig out the trenches began the week of Jan. 16, 1970 — but the project didn’t proceed on schedule. After construction delays and the city’s financial crisis, subway trains wouldn’t run over the tube’s upper level until 1989. And LIRR service on the lower level wouldn’t launch until last year, when the MTA finally cut the ribbon on its long-delayed Grand Central Madison terminal in Midtown.

Anatomy of a New York City subway crash: Dozens of decisions and a derailment In Central Brooklyn, a dreaded subway bottleneck grinds trains to a halt After 10 years of Vision Zero, NYC has a new ‘Boulevard of Death’ G Whiz: MTA proposes partial 6-week shutdown of G train this summer