Is NYC ready for summer heat? An environmental watchdog doesn’t think so.

July 5, 2023, 9:01 a.m.

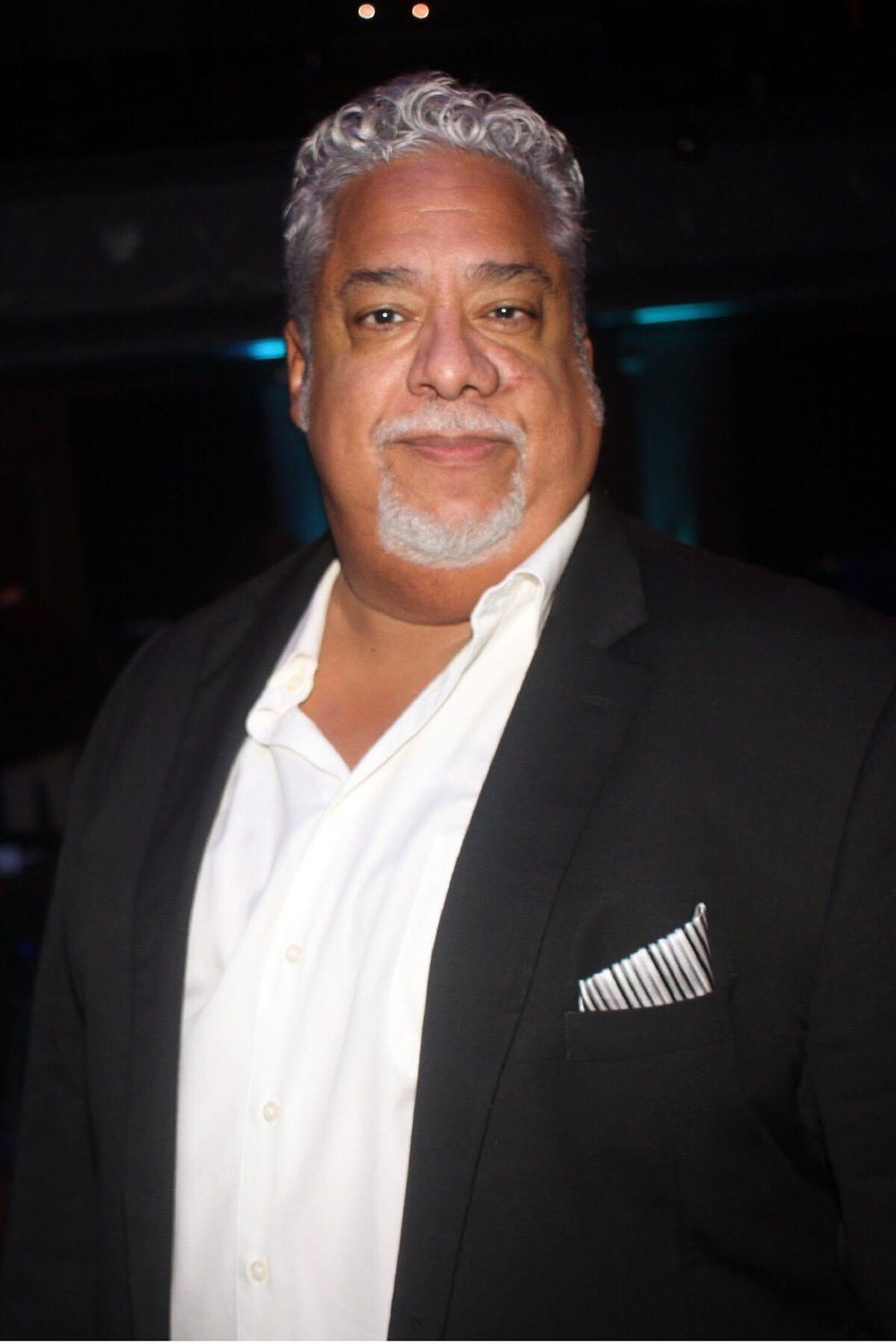

A Q&A with Eddie Bautista, executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance.

Summer heat is back and Eddie Bautista says New York City isn’t ready.

“There appears to be, at least from our perspective, a real lack of urgency,” said Bautista, executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance.

His nonprofit – a network linking grassroots organizations from low-income neighborhoods and communities of color across the city – has been monitoring city government’s efforts to keep people safe from the heat, which can be a life-or-death issue for many who live in under-resourced communities.

The City Council passed a set of bills in 2020 intended to ensure the city could better respond to extreme heat, including a bill requiring a citywide plan on how to keep residents cool on hot days and inform people about heat-related emergencies.

Spokespeople for Mayor Eric Adams did not respond to a request for comment, but the NYC Emergency Management website details some of the city’s initiatives.

It notes that during periods of extreme heat, the city opens air-conditioned spaces called cooling centers, and installs spray caps on certain fire hydrants. The city also provides a map with locations of water fountains, tree cover, sprinklers, and pools to beat the heat.

Bautista said the city can do a lot better and needs to, given the imperative of climate change.

New York City has already broken heat records this year, ahead of an anticipated hotter-than-usual summer. The city Panel on Climate Change predicts that the number of days with temperatures above 90 degrees is expected to at least double, and the number of heat waves will triple by the 2050s.

Studies show the consequences of extreme heat are most dire for low-income Black and brown residents. Lower-income neighborhoods face higher temperatures in already hot urban areas, due to an uneven spread in vegetation and buildings. And because of longstanding racial inequities in housing, health care, and other spheres, Black New Yorkers are twice as likely to die from heat-related causes compared to white residents, according to the city’s most recent data.

Gothamist recently discussed the city’s head readiness with Bautista. The conversation was edited for clarity and length.

What do you think of the city’s plan for extreme heat? Are we ready for the coming heat waves?

At the risk of oversimplifying, my sense until now is that it's pretty, pretty straightforward and underwhelming. The city's plan is a combination of painting roofs white, increased vegetation and green infrastructure and canopy, and cooling centers.

Just because the city has a plan doesn't mean it's an effective one. On multiple levels, it's barely a Band-Aid. And there's so much more that the city can do to make the cooling centers function so much better, be so much more available, especially to disproportionately vulnerable New Yorkers.

Your group conducted an audit to assess the city’s cooling centers. What did you find?

We had staff call all the cooling centers that serve our members (in summer 2019 and 2021). Some of the places they called didn't answer. Other places that they called were not aware that they were cooling centers. One or two didn't have air conditioning. There's no signage. The hours of operation are inconsistent.

There appears to be, at least from our perspective, a real lack of urgency. The level of urgency that mayors take for snowstorms, if they would apply that to climate change, we would see, I think, the kind of uptick in resources and attention and urgency that's lacking right now.

Mayors have lost elections because they botched snowstorms. That's why they care. They don't care about heat because that’s not something that is yet high in the public consciousness.

Has the city’s readiness improved?

It’s unclear. There appears to be some movement after these laws passed. The city’s taking this stuff a little more seriously and being better organized. How well and how much? We need to see. We need to have them come in and report in an oversight hearing to the council precisely what they've done to make things better and to expand access.

Some of it has already started, but yet we've got more to go.

You have other concerns with the cooling centers?

One of the foundational problems with the cooling centers is the city’s reliance on facilities funded by the city but operated by others. They are run by someone else, by a private nonprofit corporation that's running the library or the senior center or the nursing home.

The city opens cooling centers where those facilities live. If you have neighborhoods that have been disproportionately denied resources compared to their white neighbors, that means facilities like libraries and senior centers may not be as concentrated in lower income communities and communities of color.

What else should the city do to take heat-related deaths seriously?

One of the things is a bill calling for a master plan to get to 30% tree canopy coverage across the city. There are other bills pushing for expansions of green infrastructure.

The question is whether the Adams administration and the City Council continue to increase the priority of extreme heat protection or not?

You’re critical of the city’s efforts to protect its most vulnerable residents, including during the poor air quality emergency in June. What’s the issue?

We are asking for the city to identify those people who can't help themselves. You're telling me you can't get masks to distribution centers in the most impacted communities when there's Canadian wildfires? And you know it’s coming? It’s mind boggling. It’s the old saying– lead, follow, or get out of the way.

New York creates list of ‘disadvantaged communities,’ ruffles feathers in the process Lawmakers pursue $15 billion plan for climate justice in New York For NYC, the legacy of redlining is in the air we breathe