Inside NYC’s Original Social Club For Mental Health

July 15, 2021, 2:47 p.m.

The city is investing $4 million to boost enrollment in mental health clubhouses.

Lyn Joseph first joined Fountain House, a social club for people with mental health issues based in Midtown Manhattan, because she needed a way to fill her time. She had dropped out of college at SUNY New Paltz and wasn’t working.

“It was not really good to have too much free time,” said Joseph, 25, who has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, ADHD, anxiety, PTSD and autism.

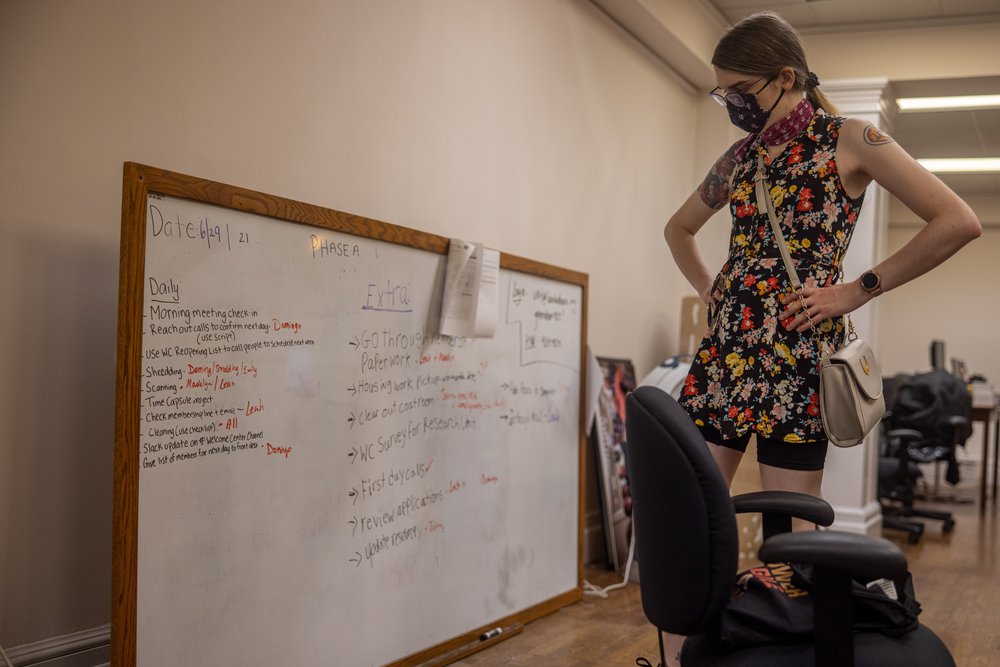

Five years later, she is contributing to the Fountain House community in ways big and small, from digitizing files in the Welcome Center to writing about fashion for the in-house newspaper. The clubhouse helped Joseph earn her associate’s degree and, during the pandemic, kept her connected to the community via virtual programming. While at home, Joseph, who is trans, launched a new group online called Queer Council with the goal of making Fountain House more welcoming for LGBTQ members.

“They saved my life,” she said of Fountain House as we sat in the clubhouse library. It was late June, and she was relieved to be back on one of the first days the center was open for in-person activity again. She said she now has the confidence and experience to look for full-time work. “I’m much more capable, I’m much more able-bodied, I’m more independent.”

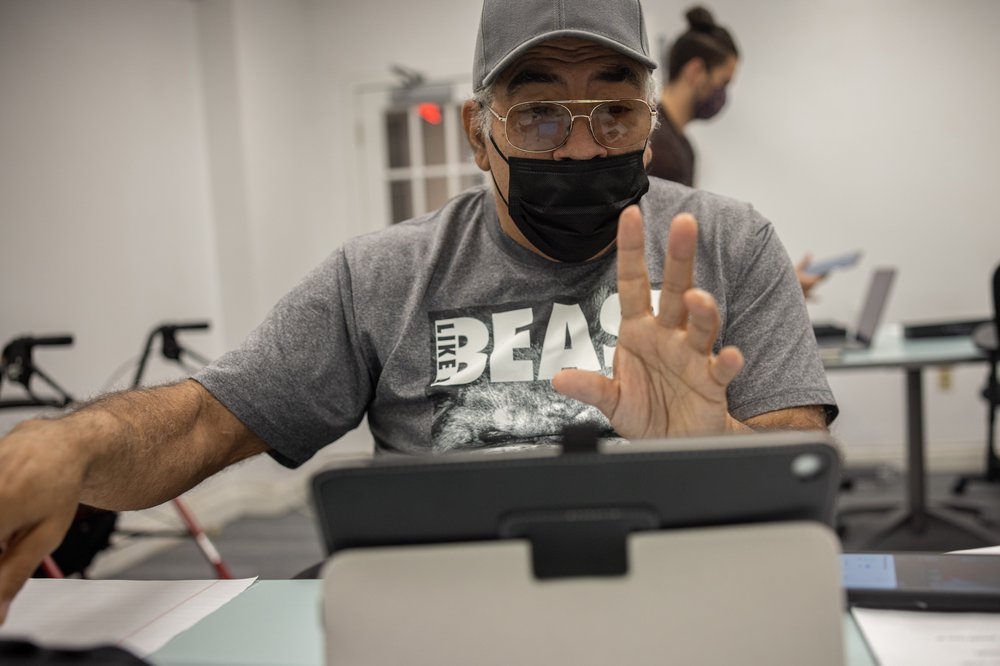

Fountain House pioneered the clubhouse model, when it was founded by a group of psychiatric patients in the 1940s. The idea has since proliferated across the globe. Clubhouses are free and voluntary to join for those with a serious mental health diagnosis, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Members run everything alongside staff, from cooking lunch to planning activities to keeping the plants alive.

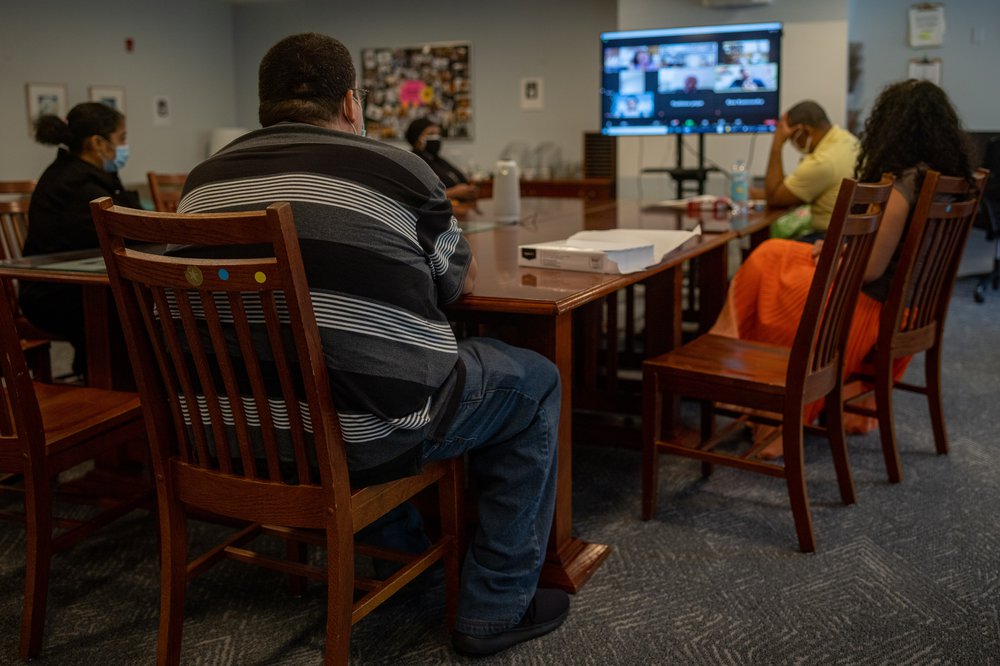

The clubhouses operate on the premise that social isolation is bad for people’s mental health, and that community and a sense of purpose can measurably improve it—a sentiment that many more New Yorkers can likely relate to given the pandemic.

“From this past year, where we've had so many people at home and isolated, we know the importance of human connections for everybody,” Myla Harrison, assistant commissioner of the city Health Department’s Bureau of Mental Health, said in an interview with WNYC/Gothamist. “And, in particular, for people with mental illness.”

After serving as a vital resource for this vulnerable population during the pandemic, the city’s clubhouses are getting an infusion of public funding to increase their membership. The effort is one of several initiatives Mayor Bill de Blasio laid out in April targeting the estimated 280,000 New Yorkers with a serious and debilitating mental illness—a population that critics initially said was not enough of a priority for the mayor’s costly ThriveNYC mental health program.

The budget the city passed in June includes $4 million for the 16 clubhouses spread across the five boroughs (14 of which are accredited by Clubhouse International, an organization that has codified clubhouse standards).

Until now, public funding for clubhouses has flowed primarily from the state, although it is administered through contracts with the city Health Department. The latest investment brings total city and state funding for the programs to $14.6 million, a nearly 50% increase over the previous year. It’s the first new public funding the city’s clubhouses have seen in two decades, according to Dr. Ashwin Vasan, Fountain House’s president and CEO.

“We've really neglected this for so long, but finally it's becoming an issue,” he said. “We see [people with serious mental illness] really disconnected and marginalized and really bouncing around in this kind of revolving door between emergency rooms, shelters, incarceration and the street.”

Clubhouses are primarily focused on building social connections and employment opportunities, as they partner with local businesses to provide people with work experience outside clubhouse walls. But the organizations also help members enroll in benefits and serve as links to services such as health care and housing. Although some studies have measured the benefits of the clubhouse model, more research is needed to demonstrate its impact, according to a literature review from 2018.

Fountain House has worked in recent years to generate metrics of success. According to the clubhouse website, 40% of members are homeless or unstably housed when they join, and 99% of those members are housed within a year. Members who were previously incarcerated also boast lower rates of recidivism than the general population.

A 2017 study from researchers at NYU found that new Fountain House members who had racked up costly bills for Medicaid prior to joining had fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits in their first year. Even as their outpatient care and medication costs increased, their medical costs dropped, by about 20% overall.

But Vasan laments that clubhouses are still undervalued. A primary care physician at NewYork-Presbyterian and professor of population health at Columbia University, Vasan joined Fountain House in 2019 with the goal of raising the profile of clubhouses and better integrating them into the behavioral health system. He is working to incorporate the city’s clubhouses—and others around the country—into a national network with shared branding and resources.

Juliet Douglas, executive director of Venture House, which operates clubhouses in Queens and Staten Island, often asks people, “What does the word ‘clubhouse’ mean to you?”

“I get answers like ‘the Mickey Mouse Club’ or ‘it's like a lodge’ or ‘it's a baseball clubhouse,’” Douglas said. “Nobody ever associates the term ‘clubhouse’ with mental health or psychosocial rehabilitation.”

Venture House has an agreement with Fountain House to join its national network, which she hopes will expand marketing and increase awareness about clubhouses among the general public.

But she emphasized that each clubhouse has its own culture and she said she wouldn’t want that to change. “We don't want to become cookie cutter like McDonald's,” she said.

Douglas said her hope is that with fresh marketing, clubhouses can become as commonplace as the YMCA. “When someone moves into a community,” she said, “they should be asking, ‘Where's the hospital? Where’s the library? Where's the school? Where’s the clubhouse?’”

This story was updated to reflect Lyn’s preferred name.