In NYC, amid deportation fears, a boom in know-your-rights sessions for immigrants

Jan. 15, 2025, 6:31 a.m.

What to do if immigration enforcement officers come calling? There’s a workshop for that.

When Donald Trump was first elected president eight years ago, students stopped showing up to a free weekly English class in Sunset Park.

Many students — largely Spanish-speaking adult immigrants — told Pedro Torres, the teaching assistant at the time, they were worried about potential immigration crackdowns. Armed with that knowledge ahead of Trump’s second inauguration, Torres has set up “know-your-rights” workshops for students.

“We need to get students prepared on what to do,” said Torres, now the head English instructor at Fifth Avenue Committee, the nonprofit that runs the English classes as well as other workforce development and social services programs. “We’ll prepare them for the worst-case scenario.”

Throughout the city, schools, libraries and community groups are offering such sessions to arm immigrants without legal status on the dos and don’ts of interacting with federal immigration enforcement officers, ahead of Trump’s promised crackdown on immigration.

The potential local audience for the workshops is considerable. The Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs, in a report last year, estimated that roughly 412,000 undocumented immigrants lived in the city as of 2022.

In a typical rights session, attendees learn about their right to remain silent when questioned by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, and the documents ICE agents may display when trying to enter their home.

Know-your-rights sessions were a frontline defense against immigration crackdowns eight years ago, when local groups expanded their community education offerings ahead of Trump's first term.

“It’s the most powerful community tool we can use to keep people from entering the detention and deportation system,” said Wennie Chin, director of community and civic engagement at the New York Immigration Coalition.

Since the presidential election in November, requests have tripled for know-your-rights sessions hosted by the New York Immigration Coalition, Chin said. The nonprofit has since more than doubled its number of weekly sessions, from two to five, and has had to turn down requests for more because of lack of capacity, she said.

Make the Road New York, which usually hosts one know-your-rights session per quarter, has completed more than a dozen since the election, according to Luba Cortés, the group’s lead organizer on civil rights and immigration.

The city Department of Education has also hosted know-your-rights sessions for immigrant families in recent weeks, and “Know Their Rights” sessions for school administrators and staff, with the educational nonprofit Project Rousseau. The agency is required to host such sessions annually under a 2017 law that requires the distribution of information about families’ legal rights, such as when students can refuse to speak with non-local law enforcement, and resources to assist families seeking immigration legal assistance.

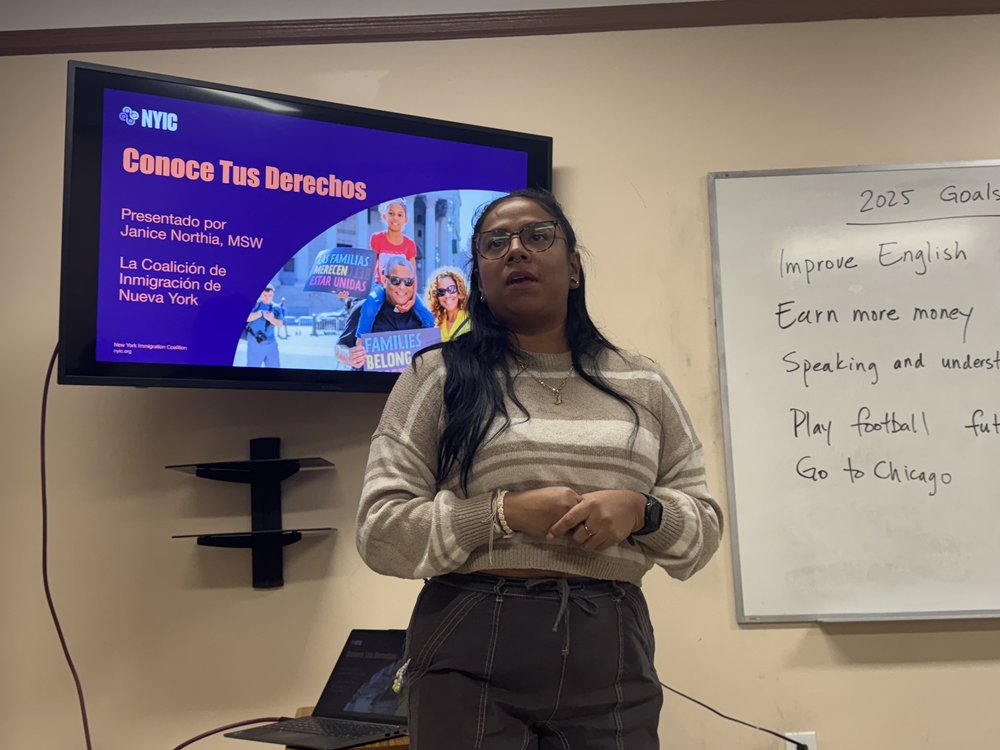

On a recent evening at the Sunset Park church where Torres’ group hosts weekly English classes, students learned about how to interact with ICE officials charged with policing immigration within the United States.

Janice Northia, a trainer, told the class that ICE agents may appear at their homes or workplaces without uniforms and in unmarked cars, and they have been known to lie or use ruses to get inside someone's home, business, or make arrests.

Attendees were advised of their right to remain silent when questioned by police and immigration agents. Spanish-speaking immigrants, reading from an instructional palm card, practiced in English what they were advised to tell immigration agents knocking at their door.

"I wish to exercise my Fifth Amendment right to remain silent,” said one man, reading from the card.

“I do not wish to speak with you to answer questions,” another participant said.

“I do not give you permission to enter my home without a warrant signed by a judge,” said another man.

According to the trainer, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents also need permission or judicial warrants to enter people's homes. ICE agents may say they have warrants, but those are often administrative warrants from within the agency that have less force, the trainer told the students.

A 30-year-old immigrant from Mexico snapped a photo on his phone of an example of a judicial warrant shared with the group. A woman wrote down the name and number of a local hotline to call to report immigration enforcement raids.

Cortés, from Make the Road, said participants often have misconceptions about their rights, and incorrectly think they have to provide all their information to the police.

“ There's a misconception that undocumented immigrants are not protected by the constitution,” Cortés said. “And that’s not accurate.”

In December, Mayor Eric Adams called for a rollback of the city’s sanctuary laws and asserted that undocumented immigrants aren't entitled to due process under the constitution. He later walked back the claim, stating that “our constitution is for all of us.”

Attendees frequently ask how to find a loved one who has been detained by ICE agents, Cortés said. They also want to know what happens to their bank account if they’re arrested. Another concern: And what happens when a parent is deported and their children are left behind?

To find detained people, ICE has an online lookup tool to find detained people, and advocates advise that family and friends know their loved ones' A-Numbers, or “Alien Numbers” to do so.

Bank accounts should still work after a deportation, Cortés said. And she suggests that parents appoint temporary guardians who can care for their children in the short-term without having permanent legal custody.

Know-your-rights information is also available on the websites of the New York Immigration Coalition, Immigrant Defense Project, and Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs.

One of the Sunset Park students, Johnny, 36, from Ecuador, who asked that only his first name be used for fear of jeopardizing his immigration case, said he has been gripped by uncertainty about what’s to come.

“At least now I have an idea of what to do, of how to prepare for the future,” he said.

NYC schools offer guidance to schools, immigrant parents ahead of Trump’s inauguration New Yorkers driven by deportation fears are flooding immigration lawyers with questions Surge in NYC migrants fuels rise in immigration services fraud complaints How President-elect Trump’s proposed mass deportations could play out in NYC – or not