If your kid has RSV, do you need to take them to the hospital — and when?

Oct. 27, 2022, 4:43 p.m.

While some are calling this moment a ‘tripledemic,’ RSV stands out from COVID-19 and the flu when it comes to its symptoms, its prevention, and its treatment.

Just when people thought it was cool to take off their masks, another airborne virus entered the fray.

A large outbreak of respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, has swept the nation, putting pressure on emergency rooms that are still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic and facing the prospect of an intense influenza season.

While some are calling this moment a ‘tripledemic,’ RSV stands out when it comes to its symptoms, its prevention, and its treatment. RSV, for example, doesn’t have a vaccine, unlike COVID-19 and the flu. And while news headlines are mostly focusing on how RSV is harming youngsters, it’s actually more lethal in senior citizens.

Here’s a simple guide on how to tell the difference between the trio of scourges and when to seek medical aid for RSV.

Who’s most at risk?

“Everyone gets infected with RSV by two years of age,” said Dr. Jennifer Lighter, a pediatric epidemiologist and associate professor of pediatric infectious diseases at NYU Langone Health, “and really that first bout of RSV is most severe.”

Over the course of a lifetime, people get reinfected, but those bouts are usually just mild colds. RSV is one of a handful of germs typically classified as cold-causing viruses.

The RSV script flips back to causing severe disease when adults become elderly or when people develop immune system deficiencies, which also happens with aging.

The youngsters most at-risk for bad outcomes are premature infants and babies under 6 months old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The federal health agency states about one to two out of every 100 children under 6 months old who catch RSV may need to be hospitalized. Children with lung, heart, neuromuscular, or immune system deficiencies also carry higher chances of severe illness.

Annually among kids younger than 5, RSV leads to 57,000 hospitalizations alongside 1.5 million visits to outpatient doctors, according to CDC data. Of those, about 100 to 500 die.

But RSV technically creates more disease burden in U.S. adults, causing 177,000 hospitalizations and 14,000 deaths per year.

The takeaways are that pretty much anyone can carry RSV — and most people will recover. But if the virus reaches a person with higher risk of severe disease, the outcomes can be bad.

OK, how do I know if it’s RSV, COVID-19, or influenza?

Many of the symptoms overlap in this tripledemic, with each one causing runny noses, coughs, and fever. But the Cleveland Clinic has a good explainer on the differences.

“In addition to a cough, runny nose, and fever, a unique symptom of RSV is wheezing. A wheeze sounds like a whistle or rattle when your child breathes,” Cleveland Clinic writes.

In addition to a cough, runny nose and fever, a unique symptom of RSV is wheezing.

Cleveland Clinic

It added that the flu is typically distinguished by a very high fever, while COVID-19 comes with increased chances of loss of taste and smell.

COVID also causes gut problems — vomiting and diarrhea – in kids.

My kid seems OK for now. How do I treat milder symptoms at home?

One thing parents might want to learn is chest physiotherapy, said Dr. Simon Li, associate professor of Pediatrics and Internal Medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and Bristol Myers Squibb Children's Hospital. That’s essentially cupping your hands and patting the back of the child to move some of phlegm up and out of their airways.

“Because usually what happens is the mucus gets stuck within the small, tiny airways of these younger babies,” Li said. Another suggestion along those lines is the use of chest percussors — soft rubber cups that can be used instead of a cupped hand.

He also recommended that parents could take a hot shower and then let the child hang in the steamy bathroom with them afterward. The humidity can help clear congestion.

Keeping the child hydrated is also important, Li said.

If things get worse, when should we head to the hospital?

Li said this decision is best made in consultation with a pediatrician, but key signs are if a sick child is breathing faster than normal or if their skin coloration looks a little bit off, such as blueness around the lips.

These problems indicate that the kid may not be pulling enough oxygen through their lungs into the body. At their worst, viruses like RSV can cause pneumonia, clogging the lungs and lower airways with mucus.

Another moderate to serious sign is a loss of appetite or if a baby isn’t feeding well.

Another moderate to serious sign is a loss of appetite or if a baby isn’t feeding well.

“What I tell parents is that a little bit of anything is OK, a little less feeding, a little harder breathing, a little tugging with their abdomen,” said Dr. Matthew Harris, medical director for crisis management at Northwell Health and the pediatric emergency medicine attending physician at Cohen Children's Medical Center in Queens. “But anything more than that really should require a visit to the pediatrician's office or the emergency department.”

If my newborn is premature and high-risk, is there anything I can do to protect them?

Premature babies or children with pre-existing conditions are often given a monoclonal antibody called palivizumab, which is sold under the brand Synagis. It’s a preventative medicine that stops the virus from replicating in the body. This drug isn’t typically used with older kids, infants without underlying conditions, or adults.

What about older kids or senior citizens?

Outside of palivizumab, there’s no specific treatment for RSV, according to The National Library of Medicine. It advises over-the-counter pain relievers for the fever and pain, though aspirin isn’t recommended for children.

Drinking plenty of fluids can also help. The worst hospitalized cases can require ventilators and oxygen support.

And, yes, mask wearing helps prevent the spread of RSV, though doctors recognize many Americans are tired of wearing face coverings. They said it’s most important for adults to wear masks around susceptible infants.

“We must keep in mind that there's significant mask fatigue related to the COVID-19 pandemic,” Harris said. “[But] if you have a high-risk child that you're visiting, certainly with newborns, it is absolutely advisable to wear a mask.”

Why are people so worried about this outbreak?

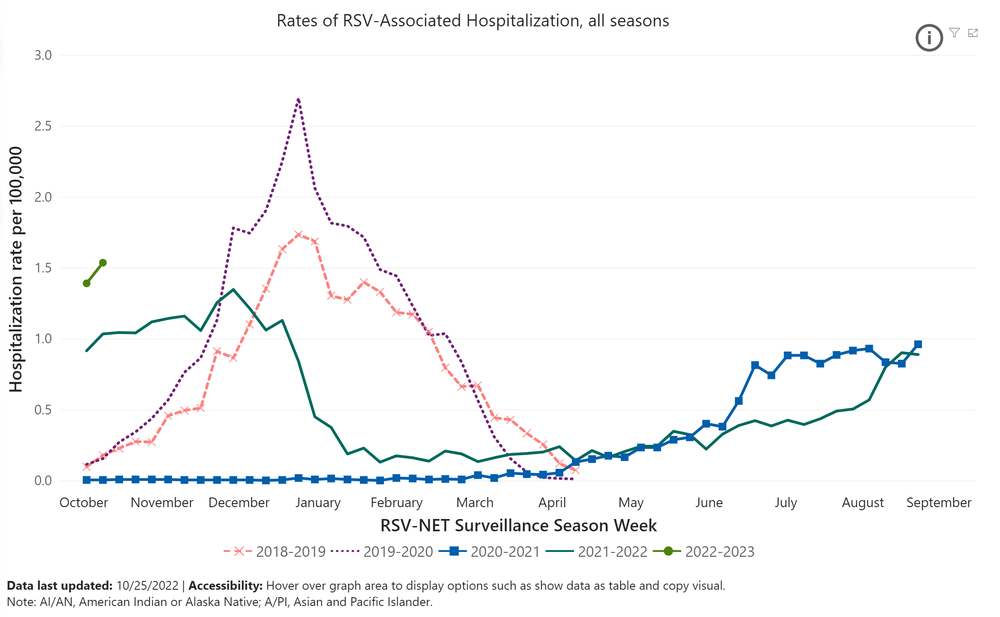

The main reason is that the outbreak has started relatively early. The Northeast and the rest of the nation are experiencing hospitalization rates now that they typically wouldn’t see until December.

This situation has put extra pressure on hospital staff, who are still dealing with workforce shortages and burnout due to COVID-19, as well as a recent outbreak of other cold-causing viruses.

“We had a surge of rhinovirus and enterovirus,” Li said, “where a lot of these kids who are very ill had respiratory illnesses.”

Li said a depleted nursing workforce is also complicating matters. The Nurse Journal is tracking the state-by-state shortage via federal labor data, showing that New Jersey ranked among the bottom 15 in 2021.

“People sometimes don't recognize how important nurses are to health care,” Li said.

How bad is the situation in New York and New Jersey?

Hospital data reported to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services shows about 75% of pediatric beds are occupied in New York, while 68% of pediatric hospital beds are taken in New Jersey. Both marks are 10% higher than the levels seen at the beginning of the summer. But those severe cases will spread themselves out differently, hospital to hospital.

“Our emergency department is seeing 40% higher volume than the equivalent time in 2019, which was our last sort of normal year prior to the pandemic,” Harris said.

CDC data shows a large RSV uptick in recent weeks — with PCR detection rates tripling in New York and New Jersey since the start of September. These rates are in line with what the area experienced a year ago — except that outbreak started a month earlier.

I hear the problem is due to an “immunity gap” — what’s that?

That’s one hypothesis. Some scientists say the pandemic lockdowns and the drop in social interactions interrupted people’s routine exposure to cold viruses. That regular exposure helps to harden individual immune systems, which in turn, provide community protection by slowing the spread of viruses. The thought is that we’re being exposed again, leading to blowback.

In reality, there’s not much hard evidence yet to support the immunity gap, which would require analyzing immune responses in a boatload of people.

“RSV had very low levels in 2020 and early 2021 because people were responding to the pandemic, and there was social distancing,” Lighter said. “But it has come back at its usual rates just a little bit earlier in the season than we expected.”

This screenshotted chart shows the CDC's Respiratory Syncytial Virus Hospitalization Surveillance Network (RSV-NET), which monitors hospitalizations in children and adults across 58 counties and 12 states. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, RSV hospitalizations started in October and peaked in January. Social distancing, mask wearing and the pandemic lockdown drove down RSV rates, and for the last two years, these severe cases have started rising in the summer.

But it would make sense that kids have less immunity?

This autumn is also the first one since 2019 where people are fully mixing again without any mask rules or social distancing. Many people are also working and schooling in person for the first time in nearly three years. That could also be intensifying the RSV outbreak.

Studies also show the COVID-19 lockdowns have thrown off the annual schedules for a number of cold-causing germs — both in the U.S. and abroad. In Japan, health researchers posited that a summertime RSV resurgence happened in July 2021 due to less population immunity and the resumption of in-person schooling.

In that vein, the Northeast saw a substantial RSV wave a year ago as schools reopened and some businesses began returning to in-person work. This surge would have also restored immunity among some communities.