How legal is it to film the NYPD? An activist tests the system online and in court.

May 31, 2023, 6 a.m.

The "Long Island Audit" is part of a growing movement of so-called constitutional activists who test whether officials will allow them to exercise their First Amendment rights.

Bystander videos have exposed countless cases of police violence in the last few decades, from the 1991 beating of Rodney King to the more recent killings of George Floyd and Eric Garner.

Now, a group of social media personalities is testing the limits of what’s legal — and what’s acceptable — when it comes to filming officers.

SeanPaul Reyes, 32, also known on social media as the Long Island Audit, films in police precincts, town halls, libraries and other government buildings in the New York area — or wherever else in the country his followers tell him to go.

He’s part of a growing movement of so-called constitutional activists, also known as First Amendment auditors, who film in government buildings to test whether officials will allow them to exercise their First Amendment rights. Many times, those officials are members of law enforcement who try to stop them from recording.

Sometimes police try to kick Reyes off the premises. Occasionally they arrest him.

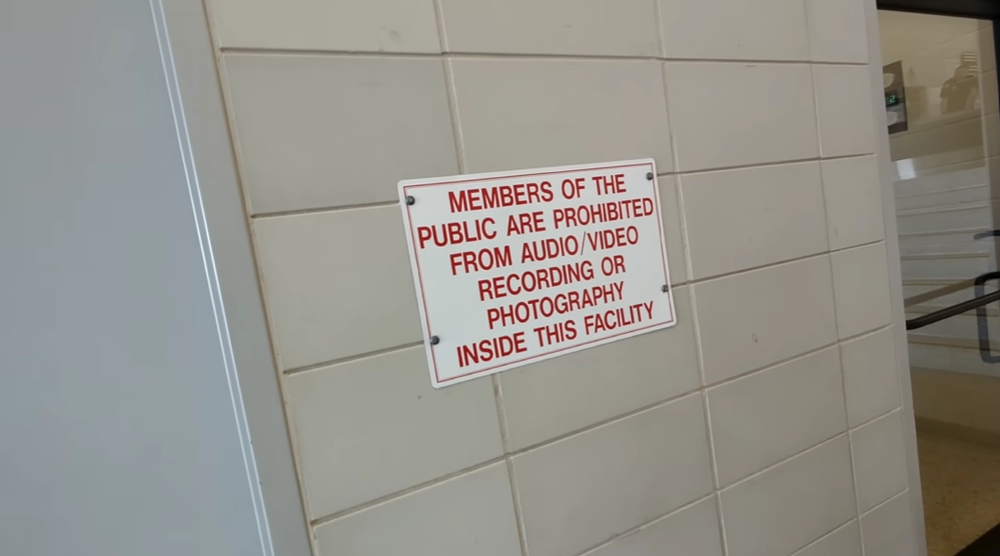

An NYPD spokesperson said filming inside precincts is not allowed because it undermines the privacy of people who interact with the criminal justice system and compromises the integrity of ongoing investigations.

But Reyes films anyway, while fervently asserting his First Amendment right to do so and challenging officials’ knowledge of the law. Lately, he’s taken a particular interest in the NYPD. The Long Island native said he is pro-law and order and considers himself a libertarian.

But since Reyes started doing what he calls “audits” during the pandemic, he has spoken with attorneys, researched constitutional law and studied police policies. He’s heard from people who say police have harmed them or broken their cellphones for recording. And he’s grown concerned about what seems to him like a lack of transparency and accountability within the department.

“All these things are happening, and these officers are still officers. Like, they're still working. They're still collecting taxpayer money,” he said in an interview with Gothamist. “And that makes me sick to my stomach.”

Reyes wants to share that knowledge with his hundreds of thousands of followers on YouTube and Facebook.

“My goal is to expose the bad officers and to try and hold them accountable through my platform,” he said.

Filming police in public places is generally protected by the First Amendment, and New York City has gone even further to guarantee people’s right to record. But there are limits to those rights, according to legal experts and law enforcement.

Still, videos of police have made it possible for the public to see with their own eyes how police treat people. They’ve sparked protests, inspired legislation and helped to secure civil settlements and criminal convictions.

At the same time, cameras can also get in the way of police work or even put people in danger, according to legal experts, police reform advocates and former officers. They have mixed feelings about whether people like Reyes are improving transparency or crossing the line.

‘A delicate balance’

Stephen Solomon, editor of First Amendment Watch at NYU, said the line between what’s legal and what isn’t when it comes to videotaping police is blurry.

“It's kind of a delicate balance that depends on the situation,” he said.

According to Solomon, filming on public sidewalks is allowed but doing so on private property isn't — unless you have permission. Filming an arrest is OK, but from a safe distance.

“But a blanket restriction typically is not consistent with the First Amendment,” he said.

Several years ago, the NYPD imposed one of those blanket restrictions, which has prompted legal challenges.

In 2018, the department banned filming in police precincts — even in public lobbies. The City Council pushed back, passing the Right to Record Act, which codified the right to tape police. The law also requires officers to track arrests and summons of people who are recording.

More than 2,700 people were arrested while they were filming police in 2021 and 2022, according to NYPD data.

One retired officer who was regularly recorded while on the force is skeptical of auditors like Reyes.

“He's really maneuvering and manipulating the law,” said former NYPD Lt. Eric Dym, who co-hosts the podcast “New York’s Finest: Retired & Unfiltered.”

Dym said people often filmed him when he worked on one of the department’s controversial anti-crime teams, doing the type of policing that led to frequent civilian complaints.

He doesn’t have a problem with anyone videotaping police. But he said officers would be less suspicious if Reyes explained what he was doing.

“I think he should approach them and say, ‘Hey, listen, I'm going to film in this area. I have the right to, I just want to let you know so that you guys don't get alarmed and feel comfortable,’” Dym said.

He added that sticking a phone in an officer’s face could be a safety issue.

“You don’t see what that cop is feeling on the scene,” he said.

Mayor Eric Adams has urged New Yorkers not to get too close.

“There’s a proper way to police, and there’s a proper way to document,” he said at a press conference last year. “If your iPhone can’t catch that picture from a safe distance, then you need to upgrade your iPhone.”

Former NYPD officer Jillian Snider said she liked it when people filmed her, because she thought it would protect her if anyone accused her of wrongdoing that didn’t actually happen.

“I had no issue with it because I'm like, you know what? You're not only protecting you, you're protecting me,” she said.

Recording as a safeguard

On a sunny Saturday last month, several dozen people holding cameras and cellphones stood in the parking lot of the NYPD’s 121st Precinct on Staten Island to protest a department policy that bans people from filming inside police precincts. The group had also come to support Reyes, who was back on the streets with his cellphone camera rolling after officers arrested him several days earlier for recording inside a Brooklyn station house.

Reyes, who wore black sunglasses and his signature baseball cap embroidered with the words “We the people,” held out his phone to capture the scene around him.

“They won’t even allow us to record inside of a precinct that we pay for,” he told the crowd of in-person protesters and online viewers tuning into his livestream. “It’s ridiculous.”

“I think it's critical that police know they're being recorded and know that if their recording comes out, they can be held accountable for their actions,” said Andrew Case, senior counsel for the group LatinoJustice.

The organization has advocated on behalf of Patricia Rodney, who was arrested for trying to film inside a Brooklyn precinct while picking up a police report for a missing blood sugar monitor. When Rodney wouldn’t put her phone down, police pushed her to the ground and broke her arm.

Rodney has sued the city in federal court. LatinoJustice and Jumaane Williams, the city's public advocate and a sponsor of the Right to Record Act, denounced the NYPD policy in an amicus brief filed last year.

“By its plain language and the clear intent of the drafters, the [Right to Record Act] was meant to protect this right as broadly as possible, including in the publicly-accessible areas of police precincts,” the brief stated.

The NYPD declined to comment on the lawsuit, which is still pending.

Case hopes if more people record police, then officers will feel more pressure to follow the rules.

“If you have a police department that believes the most important thing is, you know, protecting themselves from the so-called threat of being recorded by the public,” he said, “you see some really terrible results there.”