How Citymeals on Wheels and other senior services are prepping for NYC's next disaster

Nov. 9, 2023, 5:01 a.m.

Some senior service providers in New York City are rethinking their emergency preparedness, both in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and in light of a changing climate and an aging population.

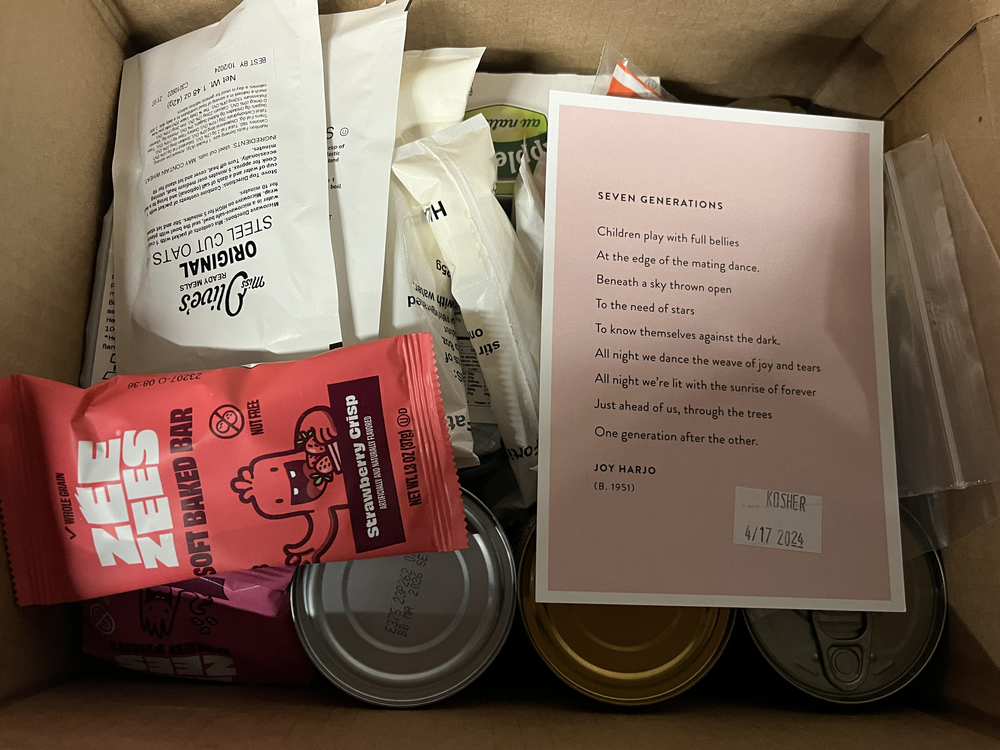

On a recent Friday morning, workers at Citymeals on Wheels’ massive food distribution warehouse in the Bronx were packing cardboard boxes with shelf-stable items like canned vegetables, pouches of tuna and salmon, and sealed, ready-to-eat meals that could be heated up or eaten straight from the container.

Each box contained enough food for six meals and would be sent to one of the thousands of homebound seniors enrolled in Meals on Wheels programs across the city. Seniors are meant to keep the boxes on hand in case extreme weather or another emergency disrupts their daily meal delivery, or their ability to get other food in the coming months.

In the past, the nonprofit sent these emergency boxes to seniors just once a year, ahead of winter, in case of a snowstorm, said Liz Cantillo, director of programs at Citymeals on Wheels.

But starting last year, the nonprofit began distributing them more frequently to prepare for a wide range of potential emergency situations, from extreme heat and power outages to the city’s recent bouts of poor air quality and flooding. Human-caused climate change is fueling many of these disasters. Citymeals first switched to four seasonal boxes last year, then decided on two larger ones this year because of logistical issues.

This seemingly small change in operations at Citymeals is one example of how some senior service providers in the city are rethinking their emergency preparedness, both in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and in light of a changing climate and an aging population. Research shows that weather events like heat waves and hurricanes disproportionately affect older adults, who also face particular health risks from social isolation.

“Some of [our recipients] have mobility issues, and they can't leave their homes. Others are those that can't cook for themselves or shop for themselves and don't have someone to do that for them,” Cantillo said. “They need our food to make sure that they eat, to make sure they have something on hand if they need to take their medication.”

Adapting to bigger storms

Citymeals is a 40-year-old organization that works with a network of 14 local Meals on Wheels programs serving about 22,000 homebound seniors across the five boroughs. Citymeals provides these partners with weekend, holiday and emergency meals to distribute, which supplement the hot food they deliver daily. Citymeals also provides partners with some financial support.

When the remnants of Tropical Storm Ophelia flooded parts of the city in late September and temporarily shut down some roads and subway lines, the Meals on Wheels programs affected by the storm were still able to make their deliveries – but it took some well-timed assistance.

For instance, food delivery drivers couldn’t access hundreds of weekend meal kits stored in the Peter Cardella Senior Center in Queens due to flooding, according to Barbara Toscano, the center’s executive director. But she said she got Citymeals to pay for drivers to pick up extra meals from a caterer they work with instead.

Still, non-perishable meal kits from Citymeals frequently come in handy, Toscano said.

“If an impending storm is coming, we notify the city, we notify everybody and we double or triple up on meals for that day,” she said.

Citymeals' CEO Beth Shapiro said she first started thinking about the need to expand capacity for emergency food operations after Hurricane Sandy. The organization moved from a smaller warehouse in Williamsburg to its current 25,000-square-foot distribution hub in 2017.

That helped position Citymeals to go from serving about 18,000 New Yorkers in 2019 to nearly 50,000 at the height of the pandemic, she said. The figure has since dropped to about 22,000 recipients.

But as the city’s population ages, the need is expected to keep growing, said Shapiro, adding that Citymeals has already had to reorganize at its new location to maximize space.

Working with seniors to adapt

For some New Yorkers who rely on Meals on Wheels programs, the delivery person they see every day is their primary contact with the outside world. That connection became even more crucial during the pandemic, when some seniors’ regular caregivers or family members were unable to visit, said Tania Collazo, director of nutrition at JASA, one of the city’s largest senior service organizations. In addition to providing senior housing and social centers, JASA runs meal delivery programs in parts of Brooklyn and Queens.

Since COVID, JASA has begun intensely training its delivery staff so they can better identify clients’ unmet needs or any changes in their condition, such as declining cognitive function or trouble hearing, Collazo said. She added that the organization has also started asking more detailed questions in its surveys of food recipients so that it can better prepare for the next emergency.

For years, Collazo said, the surveys were limited to questions like, “How do you like the meals? What do you like? What would you change about the program?” Now, she said, the questionnaires have expanded to ask clients if they have family nearby and what they think they might need in specific emergency situations.

Clients are also being asked things like, “What did you need during the pandemic that you felt like you didn't have? What made you afraid?” Collazo said.

Tapping older New Yorkers for their knowledge and asking them about their experiences in past emergencies are among the key recommendations from a recent report published by the New York Academy of Medicine on how to improve resiliency for this population post-COVID.

“They're the ones that know best how to help themselves and how to help other organizations and professionals help them,” said Elana Kieffer, one of the authors of the report, which came out of interviews with senior service providers and focus groups of older adults.

In a new book, “Climate Resilience for an Aging Nation,” author Danielle Arigoni calls for emergency planning and infrastructure that specifically takes older adults' needs into account.

“Name the disaster and, basically, you can point to evidence that older adults are disproportionately represented among the deaths,” said Arigoni, who previously served as director of livable communities at AARP and is now managing director for policy and solutions at the National Housing Trust, an organization dedicated to expanding affordable housing.

Arigoni suggested that Meals on Wheels programs are uniquely positioned to communicate with older adults who may otherwise be isolated, and the organizations could potentially expand beyond their existing services. She said they could be used to get “better information into the hands of people who are vulnerable, people who can't leave their homes, people who need some support to understand how to prepare for the eventualities of flooding or power outages or heat waves.” The city government’s communication faced criticism for its response during Ophelia and the air quality crisis in June.

Speaking on emergency planning more broadly, she pointed to the utility of special needs registries, where people could declare ahead of time that they use a wheelchair, are hearing impaired or live alone — and then specify if they need a certain type of support in case of an emergency.

Lorraine Cortes-Velazquez, commissioner of the city's Department for the Aging, said her agency is continually working to update its emergency preparedness guidelines.

Cortes-Velazquez said one of the key shifts among senior service providers in recent years in response to rising temperatures has been the focus on ensuring that older adults who qualify get government assistance with installing and paying for air conditioning, rather than only relying on the city’s cooling centers. Seniors who were given free air conditioners through a city program at the height of the pandemic were less likely to feel sick and more likely to be able to stay home on hot days, a study found.

But now, those in need of an AC must rely on the Home Energy Assistance Program, which is state-run and federally funded. While that program has expanded in recent years, it still frequently falls short of demand.

This story was updated to correct the spelling of Danielle Arigoni.

NYC schools are getting $282K grant to help stop kids from vaping When NY doctor leaves trail of injuries, a father asks, ‘When are they gonna say enough’s enough?'