How an 8-acre green roof atop the Javits Center is boosting NYC’s biodiversity

Oct. 30, 2023, 5:01 a.m.

Green roofs provide urban habitats for wildlife as well as benefits for humans, including protection against floods, heat and cold. But less than 1% of New York City's potential building top spaces utilize them.

It’s migratory bird season, and ecologists are cataloging the large number of birds that stop and refuel in New York during journeys that can reach up to 1,000 miles. On a recent Thursday afternoon at one of these pit stops, crickets drowned out the metallic grind of heavy construction and roaring traffic in Midtown.

Within an apple orchard, small bright orange and blue-gray falcons known as American kestrels home in on the high-pitched chirps of their favorite insect delicacy. But this verdant scene did not come from Central Park; it was taking place atop the Jacob Javits Convention Center along the busy Westside Highway.

Thanks to a project managed in partnership with the NYC Audubon and the company Brooklyn Grange, half of the Javits Center now has a green roof. Organizers completed the installation of 7 acres of this landscape back in 2014, and it now serves as a sky-high bird sanctuary with a bustling colony of around 160 herring gull nests. In 2021, Brooklyn Grange added another acre to the roof, creating a food forest featuring pears and mango-like paw paw fruit, as well as a year-round farm with a greenhouse.

The roof’s benefits extend beyond creating a home for animals pushed out of the city, according to NYC Audubon; this layer of vegetation can protect the city against climate change, flooding and extreme heat, while also extending the engineering life of the roof itself.

This green roof is a respite from the surrounding 300 square miles of inhospitable human habitat of mostly asphalt and concrete that makes up New York City. The bird sanctuary aims to correct the convention center’s deadly past. Before a $452 million renovation more than a decade ago, the Javits Center's large glass windows killed 4,000 to 5,000 birds a year, making it one of the city's biggest bird killers.

“[Dead] birds were piling up as people were walking into conventions,” said Dustin Partridge, director of conservation and science at the NYC Audubon.

Overdevelopment has played a major part in the decline of birds in the New York region. In the last four decades, habitat loss has been the main contributor to a 80% to 99% drop in New York grassland bird species. Between 90,000 to 230,000 migratory birds die annually because they are disoriented by the New York's reflective glass and artificial lights.

But now, instead of crashing into the building, migratory birds have a place to rest their talons and feast among the rows of the roof’s thriving farm. Five Brooklyn Grange farmers maintain the crops using only natural pesticides and fertilizers, and grow up to 50 crops each season.

“We're growing everything from A to Z – arugula to zucchini,” said Orion Ashmore, manager of the Javits farm, which is in its second season. “We have grown at least 16,000 pounds of produce up to this point in the year.”

The cityscape can also be inhospitable to its creators. New York's roughly 1 million buildings and more than 6,000 miles of asphalt roads contribute to the urban heat island effect as well as runoff resulting from impermeable surfaces. Green roofs are a way to retrofit the urban landscape to bring back wildlife while improving air quality and protecting the city against floods and extreme heat, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Green roofs offer benefits beyond lush aesthetics, such as good habitats for wildlife pushed out of urban areas and resiliency against flooding and heat. According to the Nature Conservancy, New York City has about 730 green roofs, representing less than 1% of the potential building top spaces available. If city landlords converted the roughly 1 billion square feet of urban rooftops into green spaces, they could handle approximately one-third of the city’s combined sewer overflow, a study showed.

“If the majority of buildings in New York City had green roofs installed, that would entirely change the character of New York City for the ecology of the city,” Partridge said. “If the city was entirely covered by a forest of green roofs that would be beneficial for us and very beneficial for the birds that are moving through and then breeding here as well.”

How a green roof works

A green roof can take on many forms. Some host a thin and lightweight, turf-like layer of succulent plants called sedum. The high-top greeneries can be an unkempt grassy field of colorful flowers like the Kingland Wildflowers across from the Newtown Creek wastewater treatment plant in Brooklyn.

Others involve several feet of soil for a small forest or more than a foot of earth for food production such as the Sky Farm in Long Island City, which is managed by the Variety Boys & Girls Club in Queens. The thicker the layer of vegetation and soil, the more effective a green roof is.

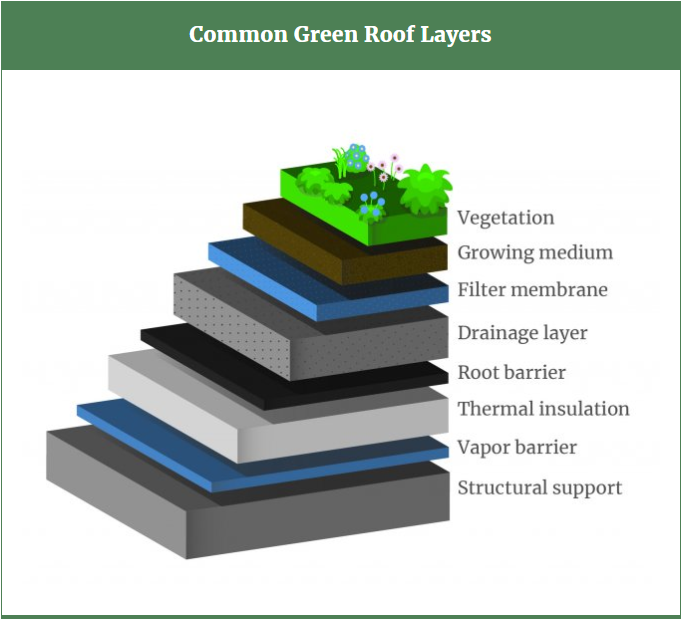

If an onlooker could peek beneath the vegetation and soil, they would see a network of parts working to protect the building while also performing added functions of drainage and insulation.

Filter fabric keeps the organic materials such as silt from washing away during storms and purifies water as it trickles down, removing chemicals, toxins and diseases.

Once the clean water passes through, a layer below retains the fluid to delay potential run-off or directs the water toward a drainage layer. The drainage layer looks like a synthetic mat or gravel. It primarily diverts water off the roof and slows down stormwater on its way to the sewer.

All of these activities can help to stymie flash floods. From a stormwater perspective, a green roof is 18 times as cost effective as using a subsurface cistern to manage the same amount of water it absorbs.

Below the drainage layer is a root barrier, which prevents plants from growing roots into the building, which could result in leaks or structural damage on the roof. This barrier also protects the waterproof lining from puncture.

The combined effort of all these layers not only protects the building from the elements but also extends the physical life of the roof, reducing how often it needs repair.

The benefits of a green roof

The thin sedum roof sitting on the south side of Javits holds about one-quarter to a half-inch of soil, but it can absorb enough precipitation to reduce the building’s runoff by nearly 80%. That’s an average rate for green roofs. For more intense rain events, the retention drops by about half or more, depending on the storm intensity and duration because the soil can only hold so much moisture.

The Javits Center's green roof retains just over half the precipitation that falls on it each year, according to Alan Steel, CEO of the New York Convention Center Operating Corporation, which runs Javits.

The roof's north side features a working farm that also captures 100% of the precipitation. The stormwater is collected in two underground tanks with a combined capacity of 344,000 gallons, where it is measured, tested and treated before it’s pumped back up to the roof to irrigate crops. The farmers prefer the treated stormwater over municipal water.

“Being on municipal water means that you're always adding a small amount of disinfectant to your soil – chlorine,” Ashmore said. “The type of farming that we're doing is really cultivating a bacterial, biologically active soil, and if you're constantly adding little bits of disinfectant over time, you are hindering my ultimate goal as a farmer.”

Green roofs are good insulators, too, and keep buildings warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer. Urban areas can get up to 22 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than suburban and rural areas due to the heat island effect. Building materials such as concrete radiate heat. A green roof is 30 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than standard black roofs, reducing ambient air temperatures by up to 5 degrees.

Using temperature cameras in 2013, Drexel University researchers compared the green roof on the north side to the black roof on the southern portion. The studies found ceiling surface temperature differences exceeded 20 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer between the two roofs. When the black roof was greened, the differences became negligible.

They also recorded outside air temperatures above the green parts of the Javits roof as 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than standard rooftops. The temperature difference was about 2 degrees between the reading from the green roof and a weather station located on street level in front of the Javits on 11th Avenue.

“It's like laying a blanket on top of the building, and it keeps you warm when it's cold, and it keeps you cooler when it's hot,” Steel said.

Animals benefit as well from having more green space. According to field observations and sensors from the NYC Audubon, five species of native bats, more than 60 species of birds and thousands of insects rely on the Javits green roof.

On approximately seven acres of sedum, about 160 herring gull nests have maxed out their colony, according to NYC Audubon. On the remaining acre of farmland and food forests, colorful migratory birds use the roof as a resting spot as they travel as far north as Toronto and Florida to the south. The varieties include yellow-green Nashville warblers, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and dark-eyed juncos.

The birds feast on the grasshoppers, spiders and ants that are attracted to the green roof. The American Museum of Natural History has helped identify 19 bee species that flit among the berry patches and pollinator gardens on the green roof, including the Gotham Sweat Bee, a species discovered in New York City about 15 years ago.

A total of nine honeybee hives make enough excess honey for beekeepers to sustainably harvest 100 pounds annually for consumption at the Javits events. The rooftop has its own live bee cam.

At night, Eastern red bats come to feast on moths attracted to the ripe, fallen apples in the roof’s orchard, which will produce more than 500 pounds of apples this year. It grows five different native varieties including Macintosh and Honey Crisp apples.

”It really shows what can happen if we start creating spaces that are kind of forgotten about,” Partridge said. “There are a lot of benefits to both people and wildlife up here, but it's kind of easy to forget where we are when we're sitting in an apple orchard in Manhattan.”

Of the 8 tons of food produced this year so far by the farm, Javits donated just over a ton to local organizations that alleviate food insecurity, such as Rethink Food. The rest is used by the convention center chefs, such as the lettuce used in burgers for this year’s Comic-Con.

“Farming is always a challenge,” Ashmore said. “I feel like we’ve really created some robust operations and systems of doing things that are really enjoyable as well.”

The cost

While a green roof can cost roughly double a standard blacktop, that only represents the upfront cash for installation. New green roofs are eligible for a one-year tax abatement of up to $15 per square foot from the city, capped at $200,000. Green roof installation costs start at $15 per square foot and can exceed $50.

Another cost factor is durability. A blacktop or white reflective roof lasts around 20 years, but a green roof’s lifespan is twice as long.

“The [green] roof's not getting hot in the day and getting cold at night because those kinds of thermal oscillations have a structural impact,” said Franco Montalto, a civil engineering professor at Drexel University, who is monitoring the Javits green roof.

The green layer also reduces air conditioning costs by protecting the roof and the building from solar radiation. During the summer, a flat black asphalt roof can reach temperatures of 90 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the air temperature. Green roofs can also insulate buildings in the winter. Both temperature attributes can reduce the carbon footprint of buildings by shrinking how much cooling and heating the overall structure needs. Buildings are the city’s biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions.

“If you're a rich person who owns a big skyscraper and you're trying to figure out how to comply with some of the stormwater regulations, a green roof is more cost effective than putting in a big tank and then not being able to develop that land,” Montalto said. “That tank would occupy real estate that otherwise would have a very high value in Manhattan.”

Last spring, the New York City Council introduced a bill to map out all existing green roofs. The legislation has been in committee for well over a year. If passed, the Department of Environmental Protection would have to publish an online map with the location, building type, size and stormwater capacity of every green roof.

Hundreds attend NYC buildings hearing about softened enforcement for major climate law

NY tentatively approves 3 offshore wind farms, including Ravenswood project

Hundreds attend NYC buildings hearing about softened enforcement for major climate law

NY tentatively approves 3 offshore wind farms, including Ravenswood project