Housing deal between Mayor Adams, Council places parking mandates on outer-borough development

Nov. 23, 2024, 11:52 a.m.

Critics say that means less incentive to build new homes and improve transit in the outer boroughs.

The deal negotiated by the City Council on Mayor Eric Adams’ signature zoning plan will require developers to build parking spaces for new housing in most outer-borough neighborhoods, after the mayor's initial proposal eliminated the mandates citywide.

The plan earned the approval of two Council committees Thursday, after the Adams administration agreed to scale back a more ambitious proposal. The elimination of parking mandates was intended to encourage new housing development across the boroughs. The new version means developers will be required to build in parking infrastructure, like lots and garages, which will drive up costs and which many fear will chill development in low-density, more suburban sections of the city.

And transit advocates say that also gives little incentive to improve mass transit access in the outer boroughs.

"While cities across the country are fully lifting parking mandates, the New York City Council chose to be less bold,” said Sara Lind with the nonprofit group Open Plans, which advocates for development that scales back “car culture.”

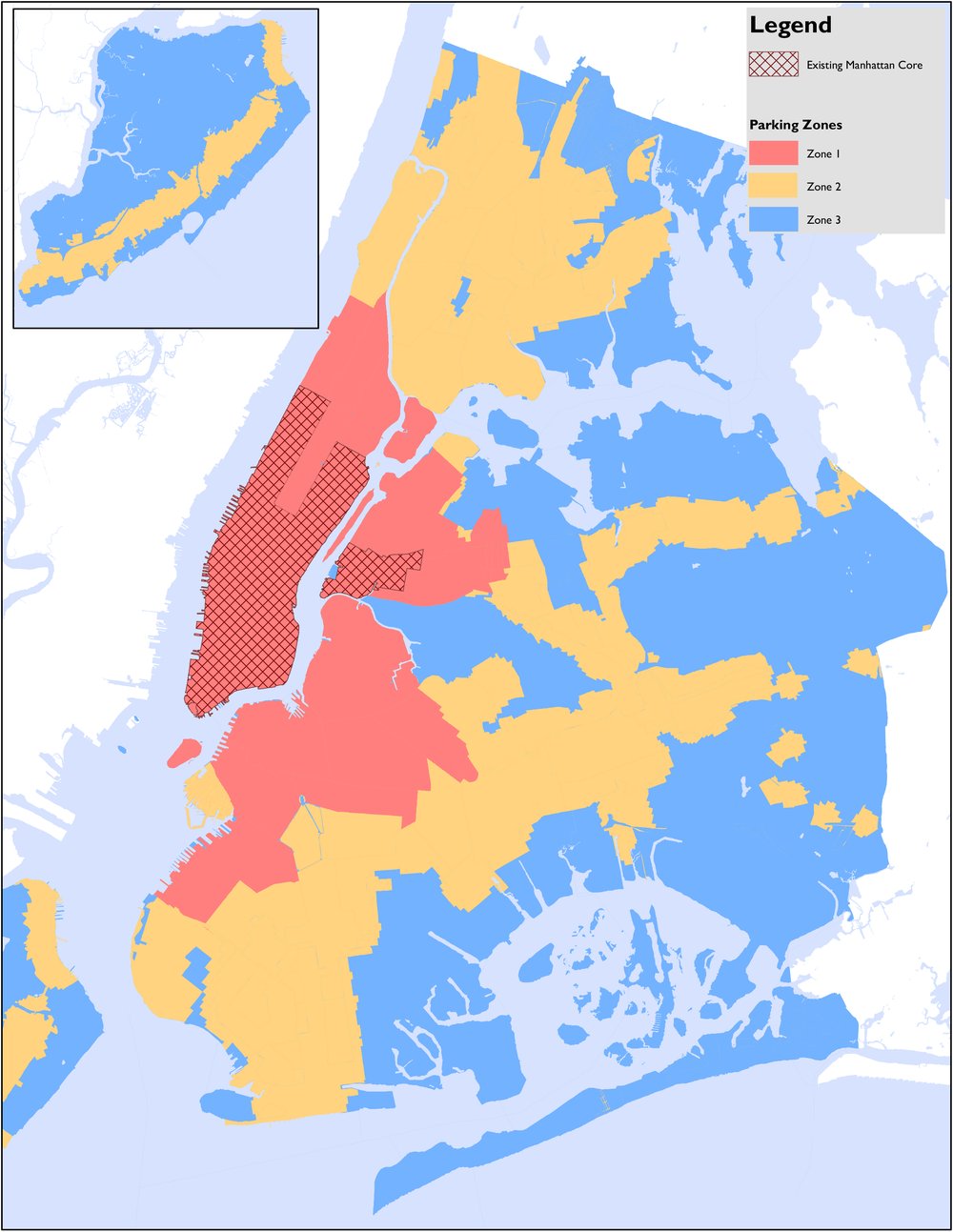

The City Council has released a map showing exactly where developers would have to build be parking infrastructure under the zoning overhaul, which Adams has dubbed the “City of Yes.”

The map’s Zone 1, in red, covers most of Manhattan, Roosevelt Island, Long Island City, the South Bronx and densely populated parts of Brooklyn including Williamsburg. There, developers wouldn’t have to include parking in new construction at all.

Zone 2, in yellow, covers most of the Bronx as well as chunks of all the other boroughs. Many requirements for parking go away there as well, including for affordable units and smaller developments near transit. That zone would keep parking requirements for other one- and two-family home construction, but scale rules back compared to current zoning.

Zone 3, in blue and largely covering the outer areas of the city, sees few changes to parking requirements for new construction — mostly keeping the rules in the areas where residents already depend most on cars for transportation.

Overall, Lind applauded the change in the zoning code, which she described as a “once-in-a-generation chance” and the largest shift of its kind in the nation. But she said it could have gone a lot farther, as “we believe far too many New Yorkers still live in car dependence and transit deserts that are encouraged in part by parking mandates.” Lind and some other advocates argue that parking mandates encourage car ownership and raise housing costs by taking up space that could be used to build more homes.

Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso said the plan unfairly keeps a burden on areas already bringing in new housing. He cited the example of Fort Greene, saying it’s already added a lot of housing in recent years — but remains in Zone 1, where the parking rules are eliminated and developers have a strong incentive to build more. Yet he said there hasn’t been as much development in Marine Park, which is in Zone 3, and won’t see much of a change to existing parking requirements.

“Now what we're saying is we want you [in developed areas] to do more while asking other people, ‘Hey, you've done nothing and it's OK, continue to do nothing,’” he said. “And that's unacceptable.”

New York City will join dozens of other cities nationwide that have moved to kick some or all parking requirements to the curb.

The new tiered system could offer some relief to critics of the plan who had targeted the mayor’s original proposal to nix parking mandates citywide. They said they feared circling blocks, unable to find places to park if new residents brought cars to neighborhoods without developers giving them anywhere to park in their new buildings.

“The lack of parking mandates within the proposal only proves how out-of-tune the ‘City of Yes’ is for our city,” Arlene Schlesinger, a member of the Hollis Hills Civic Association in Queens, said at a Council hearing last month.

Several councilmembers supportive of the overall goal of housing creation, likeCouncilmember Kevin Riley of the Bronx, also singled out the original plan to do away with parking mandates. He said the city’s planning department, in crafting the mayor’s original proposal, didn’t consider the driving needs of people in neighborhoods with pokey buses and no trains.

The parking compromise was politically necessary to actually earn the Council’s support, said James Power, a partner at the law firm Kramer Levin who advises developers.

But he said the effects won’t be as severe as critics fear.

Power said many developers will still opt to include parking in their projects to appeal to prospective tenants or condo buyers, even if the spots aren’t required.

Under current rules, developers often reduce the size of projects to avoid parking requirements — a cost-benefit analysis “undermining housing supply in New York,” Power said.

He said eliminating parking requirements in at least some sections of the city would lead to lower construction costs — especially when it comes to excavating below-ground lots — and allow developers to instead build more apartments.

“Providing parking makes a project more expensive and can in many cases reduce the number of housing units provided,” Power said.

A previous version of the mayor’s plan to fuel housing development would have changed zoning rules to allow for up to 109,000 new homes over the next 15 years, planning officials estimated. The new version, negotiated with the Council this week, would allow the construction of as many as 80,000, they now say. The deal includes funding for sewers, streets and parks, as well as more staff at city housing agencies and commitments from the mayor to invest in more affordable housing.

City Planning Director Dan Garodnick said the new plan struck a careful balance by lifting the parking mandates in areas with good transit access.

“At the same time, they ensured that the plan continues to enable significant new housing city-wide, including a little bit in every neighborhood,” he said in a statement. “I applaud their thoughtful consideration and hope the full City Council approves the plan in a couple of weeks.”

The plan will face a full Council vote on Dec. 5.

Mayor Adams, NYC Council strike last-minute deal on sweeping housing plan amid historic crisis Curb space makeover on Upper West Side will bring new bike racks, more public seating NYC’s 1st dedicated soccer stadium named Etihad Park after United Arab Emirates airline