Home care workers turn to New York City Council to outlaw 24-hour shifts

Aug. 31, 2022, 11:01 a.m.

If successful, the measure would end a practice in which New York home care workers are assigned to 24-hour shifts and paid for just 13 hours of their time.

A bill that would make it illegal for home health aides to be assigned to shifts of more than 12 hours at a time is gaining steam in the New York City Council, after a similar piece of legislation stalled in the state legislature.

If successful, the measure would represent a major step forward for grassroots labor activists who have been fighting for years to end a practice in which New York home care workers are assigned to 24-hour shifts and paid for just 13 hours of their time.

The bill now has 29 sponsors in the 51-member Council as well as the support of the city’s public advocate. But discussions may heat up at a Council hearing on the measure next week. The proposal is pitting the highly influential 1199SEIU health care union — which is fighting the bill — against its members in the home care sector, many of whom are women of color.

Some home care patients and advocates are also opposing the bill over concerns about how the new rules would affect disabled and elderly New Yorkers who rely on home health aides to avoid being placed in nursing homes. One fear is that the new rule is too strict when it comes to the number of hours an aide can work, putting patients at risk of being left unattended so home care employers don’t get fined.

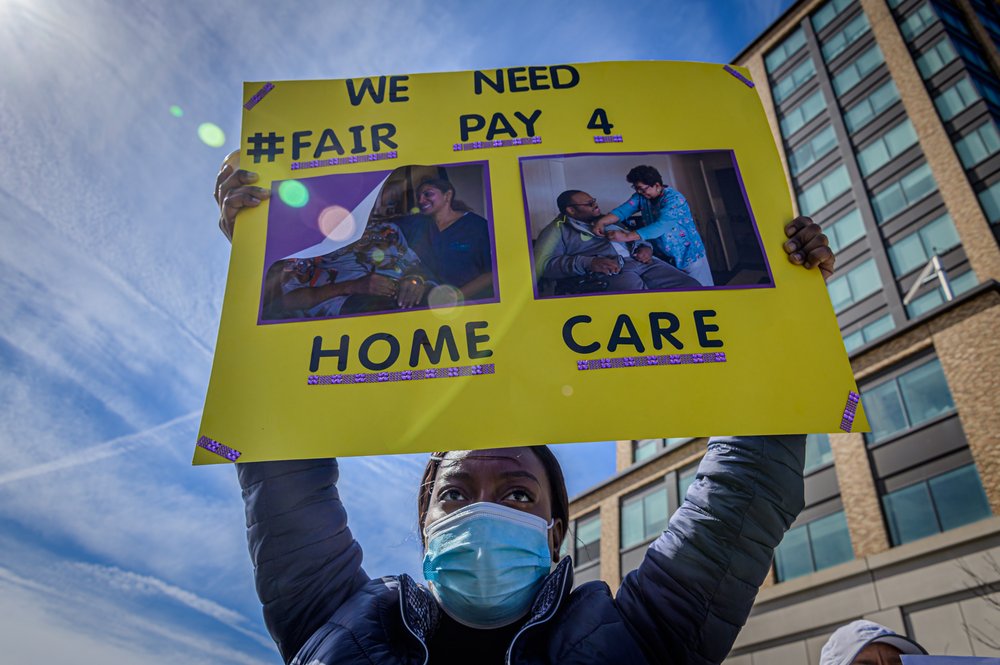

Home care activists with the Ain’t I A Woman campaign are rallying in front of the 1199SEIU headquarters in Manhattan Wednesday — in part, to call on union president George Gresham to support the bill.

“The years of working grueling 24-hour shifts without sleep have taken a toll on our health, inflicting injuries and permanent disabilities in our hands, arms, legs, and backs — and causing most of us to suffer from insomnia,” home care workers wrote in an open letter urging Gresham to speak out in favor of the “No More 24 Act.”

In addition to capping each shift at 12 hours, the bill would also prevent employers from assigning home care workers in the five boroughs more than 50 hours per week.

In a statement to Gothamist, 1199SEIU said it “does not support the concept of 24-hour shifts,” but opposes the Council bill to end them “because it would unfairly restrict workers from the ability to earn the overtime pay (which they rely on to support themselves and their families) by capping the workweek to 50 hours.”

Sarah Ahn, a spokesperson for the Ain’t I A Woman campaign, said workers might be open to a higher limit on the number of weekly hours if 1199 was willing to collaborate on the bill.

The union and other critics said they also worry the bill will not be paired with the additional home care funding and staffing needed to split each 24-hour shift in two. The state’s home care industry has already been facing staffing shortages, noted Al Cardillo, president and CEO of the Home Care Association of New York, which represents home care employers.

The most recent state budget boosted the minimum wage for home care workers by $3 per hour — although that figure fell short of the 50% wage increase advocates were seeking.

Councilmember Crystal Hudson, who chairs the Committee on Aging, has yet to sign onto the local legislation. She says she’s waiting until after the hearing to take a position.

“We're hearing from a lot of patients and patient advocates who are just concerned that they're not going to be able to get the care that they need if this bill moves forward without further intervention from the state,” Hudson said.

Will the Hochul administration get on board?

Much of the 24-hour home care in New York is funded and regulated by the state Medicaid program under the Department of Health. Some high-need patients already get approved for so-called “split shifts,” in which one caregiver comes in the daytime and another at night. But other times a Medicaid plan approves a patient for round-the-clock care with only one aide for the full 24 hours.

This arrangement is more budget-friendly since, under state policy, a home care worker can be paid for just 13 hours of a 24-hour shift. The rule is based on the assumption that aides will be able to eat and rest during the other hours they spend at their clients’ homes, and that they will get compensated for the full 24 hours if they don’t get the sleep and meal time required under the law.

But aides who work 24-hour shifts have been saying for years that they routinely have to tend to their patients overnight and miss out on both rest and fair pay.

“It’s not predictable when care has to take place,” said Councilmember Christopher Marte, a primary sponsor of the bill. “What we want to do is make sure that every hour that they work, they're getting paid for.”

Asked whether the state is prepared to adjust its home care policies and budget if theCouncil bill becomes law, New York State Department of Health spokesperson Monica Pomeroy simply said the agency doesn’t comment on pending legislation. She declined to provide an estimate of what it would cost to make the policy change.

Gov. Kathy Hochul’s office did not respond for comment.

Bronx resident Jose Hernandez said he has had round-the-clock home care since he suffered a paralyzing spinal cord injury in 1995. He said he would support state legislation to end 24-hour shifts, but is opposed to the City Council bill because he is worried it will clash with state policies and patients will be caught in the middle without sufficient safeguards.

“Where this bill falls short is in addressing the issue of patients being left alone,” said Hernandez, who is a community organizer with the Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Association of New York State, a group that represents home care consumers.

He also worried the City Council bill doesn’t sufficiently address what happens if a home aide’s 12-hour shift is up and another caregiver hasn’t shown up. The bill would levy fines against any home care agency that keeps an aide in a patient’s home longer than 12 hours, with only limited exceptions for an “an unforeseeable emergent circumstance.”

The bill notes that even then, aides can’t be kept more than two additional hours in a day or 10 in a week.

Feuding over stolen wages

As home care workers seek to end 24-hour shifts, some are also still trying to get fairly compensated for the ones they have worked in the past.

In February, 1199SEIU declared victory after securing an estimated $30 million in back pay for home care workers who had been underpaid by their employers, including for 24-hour shifts. The union now says, after further assessment, the fund is closer to $40 million, with more than 40 home care agencies paying into it.

The deadline for affected workers to submit a claim for their share of the money is Sept. 27 and 1199SEIU says close to 25,000 people have done so already.

But current and former 24-hour home care workers with the Ain’t I A Woman campaign have denounced the deal. Many initially tried to pursue lost wages in court through class-action lawsuits. The union prevented cases from moving forward by putting clauses in workers’ contracts that said wage disputes would be settled through private arbitration — a process the union maintains is more efficient than a lawsuit and less expensive.

But workers worry that the road of arbitration has also led to lower payouts. The award the union got through that industry-wide arbitration process was initially slated to cover some 100,000 current and former home care workers — so that, at first glance, each person would get only about $300 on average. It’s likely that, based on the formula for distributing the funds, some individuals stand to receive a lot more than that — although it’s unclear exactly how much.

The Ain’t I A Woman campaign is encouraging people to hold off on accepting the award until 1199SEIU can tell them how much each individual will get. They will be demanding those answers at the rally at 11 a.m. Wednesday.

An 1199SEIU spokesperson said it’s impossible to tell people ahead of time because it depends on how many claims are received and how many shifts need backpay.