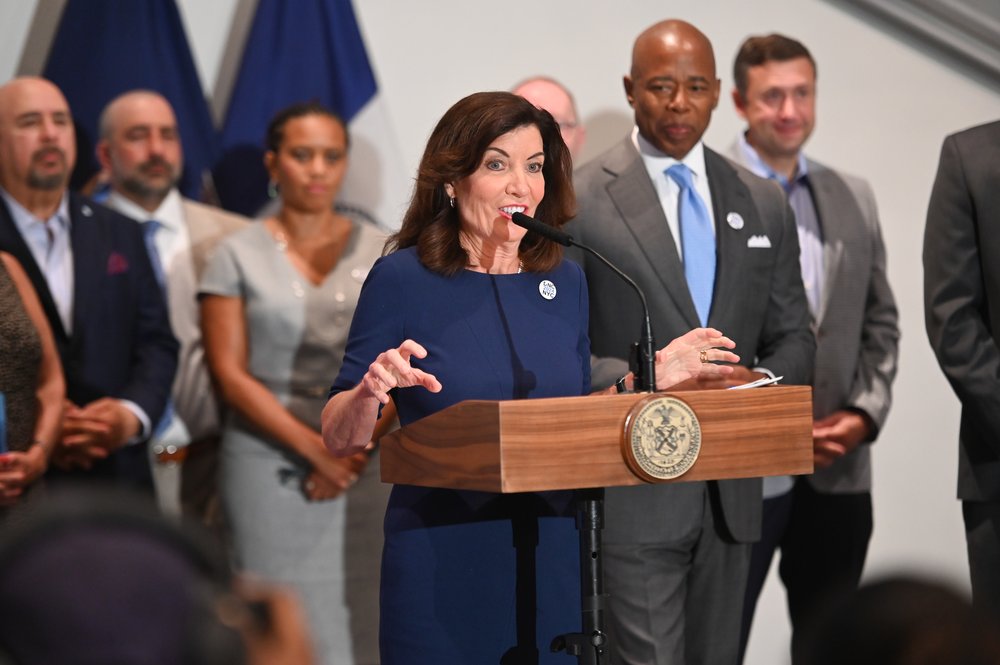

Hochul, Adams have big housing plans; some question whether they can deliver

Jan. 16, 2023, 11:01 a.m.

The two Democrats last week unveiled a host of initiatives aimed in part at producing more affordable housing.

As someone who has struggled with housing for years, Arelis Figueroa is the kind of New Yorker who could stand to benefit from the ambitious housing proposals put forth in recent days by Gov. Kathy Hochul and Mayor Eric Adams.

The two powerful Democrats last week doubled down on shared policy initiatives aimed at making the city and state work for more people. Hochul called for building 800,000 homes and touted a proposal that would boost wages for the lowest earners. Adams added new detail on his “moonshot” call for 500,000 homes, including affordable units in repurposed office buildings.

But for Figueroa, who lives in multigenerational housing on the Upper West Side and yearns for her own apartment, her reaction to the grand policy pronouncements was more muted than hopeful. “They keep saying that,” Figueroa said of the ambitious plans, “but what I keep seeing is a lot of luxury buildings going up, all over the place.”

Reactions from policy analysts and other observers were similarly restrained, with some noting the herculean task of changing course in a city where economic inequality is a defining feature from neighborhood to neighborhood. At the same time, there was some appreciation that the two leaders, in their policy prescriptions, were at least sounding the same notes.

It is positive that the conversation is shifting to recognize that it can’t be business as usual.

Kellie Leeson, a co-lead organizer with Empire State Indivisible

“Gov. Hochul’s priorities – public safety, affordable housing, and the mental health crisis – are in line with the top concerns of New York’s major employers,” said Kathryn Wylde, the president of the pro-business group Partnership for New York City, in a statement. “These issues represent the biggest post-pandemic threat to the livability and economic vitality of our city and state."

Kellie Leeson, a co-lead organizer with the progressive grassroots group Empire State Indivisible, sounded a hopeful note. “It is positive that the conversation is shifting to recognize that it can’t be business as usual,” Leeson said.

But there also were expressions of frustration.

“We’re concerned that just emphasizing 800,000 units or 500,000 units without specifying the income-targeting and affordability levels of those units is repeating mistakes of the past,” said Jacquelyn Simone, the policy director at xthe Coalition for the Homeless,. “So we would hope that the mayor and governor are more specific in ensuring that they’re producing deeply subsidized, affordable housing for the people who need it the most.”

'Cutting red tape'

Hochul’s plans, which were announced on Tuesday, included requiring New York City and its surrounding suburbs to expand their housing stock by 3% over each of the next three years. Under federal fair housing guidelines, suburban communities are obligated to consider the housing needs of surrounding communities, but have been notoriously slow to add housing, particularly of the affordable kind.

Hochul also said she’d seek a replacement to 421-a, a controversial tax break that slashed developers’ property taxes in exchange for hitting modest affordable housing goals, and which expired last year. Like the governor, Adams, who unveiled what has been described as a “no-frills” budget last week, has proposed easing zoning restrictions that stymie the creation of new housing. He is also pushing for the conversion of office buildings into as many as 20,000 new apartments.

During his State of the City speech on Thursday, Adams said, “New Yorkers have been suffering from our housing crisis for far too long.”

“We are cutting red tape to make it easier to build and upgrade affordable homes for New Yorkers,” he added, “and we are assisting our low-income neighborhoods with down payments, tenant protections and more through our ‘Housing Our Neighbors' and 'Get Stuff Built' initiatives.”

Leeson said she was heartened by Hochul’s statement that “housing is a human right.” As with childcare and mental health care, Leeson said, the state’s affordable housing crisis has been building “for the last couple of decades” before exploding during the pandemic, something she frequently heard from voters during an unsuccessful run for state Assembly last year.

“There definitely is critical mass that this is not working and we need to do something different,” Leeson said. “We’ve always known New York is expensive. Right now, it’s just too much.”

'Reimagining' proposals

For Hochul and Adams, the proposals are a follow-up to the wide-ranging report they unveiled in December that called for a “reimagining” of Midtown and Lower Manhattan as neighborhoods “where people live, work and play 24/7.”

Their action plan, which is aimed partly at countering an expected continuing soft demand in Midtown and Lower Manhattan office space, also calls for a wider variety of jobs in the central business district, as well as more affordable housing, something Hochul acknowledged was available to earlier generations of working families in a way it isn’t today.

Sticking with the theme of reaching out to New Yorkers with fewer resources, Hochul said in her State of the State address, "As a matter of fairness and social justice, I am proposing a plan to peg the minimum wage to inflation." She received a standing ovation.

“My parents started married life in a trailer park,” she said during her State of the State address. “On my dad’s salary from the steel plant, they eventually were able to live in a tiny upstairs flat. And from there, they saved up and got a little Cape Cod house. As we grew older and my dad changed jobs, I watched my parents’ success unfold through the progression of homes they could afford.”

But housing advocates say New York needs more on the policy front, including more immediate tenant protections. These include “Good Cause Eviction,” a bill that was introduced in Albany as a way of preventing steep rent hikes for an estimated 1.6 million households but has faced steady opposition from real estate groups. Another is the Housing Access Voucher Program, a rental assistance voucher that Hochul has reportedly said would be too expensive to fund but which has the support of housing organizations.

More shortcomings

Some advocates said Hochul’s proposals failed to recognize the urgency of the housing crisis.

“Hochul’s plan will take decades and totally ignores tenants' pain right now,” said Andrea Shapiro, the director of programs and advocacy at the Met Council on Housing.

For Shapiro and others, government interventions are critical, given the shortage of housing stock.

“New York City is in a housing emergency, which means we have less than 5% vacancy, this means we are fundamentally a landlord's market,” said Shapiro in an email. “The free market can't work. That is why we have the rent laws, they are anti-price gouging measures.”

Count Figueroa among those looking for answers – some of which may come as state lawmakers, members of the City Council, community boards and others hold public hearings and hash out the plans' details.

Having long doubled up on the Upper West Side with her sister, nephew and 86-year-old mother through the course of the pandemic, while also raising a preteen daughter, Figueroa said she yearns for her own apartment but is wary of placing too much stock in elected officials.

Figueroa has a master’s degree in theology. She serves as a pastor for a Hispanic ministry and has also taught ESL classes, but saw her hours reduced considerably early in the pandemic. Last year, she said she earned around $30,000. The inability to afford her own place has been a source of frustration. She said others in her circle face similar struggles.

“I have a friend who was telling me sometimes she just can’t eat,” said Figueroa, “because she has to pay the rent.”