For asylum seekers, Manhattan is only part of a harrowing journey

Sept. 23, 2022, 6 a.m.

These migrants from Venezuela braved jungles, wild animals, and the Port Authority Bus Terminal to call the U.S. home.

After undertaking a journey of thousands of miles that led him from his home in Venezuela through the perilous swamps and forests of the Darien Gap, up through Mexico, and straight into the heart of a U.S. border controversy, Gonzalez gazed, with eyes widened, upon a discarded microwave oven, cast out onto an Upper West Side curb. Back in Venezuela, Gonzalez observed, no one would have junked such an item; it would have been sold.

“Mucha plata,” he said, rubbing his thumb and his fingers together in the international gesture for money. Gonzalez, a 37-year-old father of three who asked that his full name not be used because of legal concerns, is one of approximately 13,000 asylum seekers who have journeyed to the city from Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, and other Latin American countries in recent months. And like many of them, he is trying to make sense of the country where he hopes to remain. It is a place of great wealth – where perfectly decent appliances are discarded. It is also a land of opportunity, which, along with the other new arrivals, he is hoping to seize.

To make that happen, Gonzalez, along with the others, is learning to navigate a humanitarian, political, and bureaucratic labyrinth that winds through jungles and urban landscapes, bus stations, and state houses, marked with any number of pitfalls – with the ultimate goal of convincing a federal immigration judge to allow them to remain. They are aided by nonprofit service organizations, networks of volunteers and advocates, government organizations, and ordinary New Yorkers, to varying degrees. And, as with Gonzalez, some receive help from those who have traveled the same path, and ultimately were authorized to remain.

“I had nothing,” he said. “When I got here, my life changed.”

In important ways, Gonzalez has resources that the vast majority of asylum seekers in New York conspicuously lack. He lives not with strangers but with people he knows and trusts, in a spacious home located in a safe neighborhood, thanks to good Samaritans who are among the legions who form a strained support network for the city’s new arrivals. He has his own bedroom and bathroom and is able to enjoy his privacy. None of these advantages, however, necessarily gives Gonzalez a leg up where it matters most, which is whether an immigration judge will ultimately approve his request for asylum, allowing him to remain legally in the U.S.

"It is too soon to tell what percentage of Venezuelans will qualify for asylum," said Stephen Yale-Loehr, an immigration professor at Cornell Law School. "Because of backlogs in the asylum process, it could be years before we will know."

Since arriving in late August, Gonzalez has stayed just blocks from Riverside Park, in a spacious and well-appointed apartment owned by a retired corporate lawyer turned activist. Another bedroom in the home is occupied by his 19-year-old nephew and his nephew’s girlfriend, who is 21. The three undertook the journey together – including a bus ride from San Antonio to the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York – and remain united.

While a small percentage of asylum seekers have left the city for other destinations, found housing with family members or other private citizens, or in some cases started working and been able to rent their own places, the vast majority who remain – an estimated 8,500 – currently reside within the city’s shelter system.

It is this population that is caught at the center of a debate over New York City’s right-to-shelter laws, and what many consider the system’s failings. “The New York City shelter system is broken,” said Ariadna Phillips, an activist affiliated with South Bronx Mutual Aid who has been assisting asylum seekers. “It's been broken for an extensive period of time.”

She pointed to recent episodes in which people living in shelters were assaulted by officers or forced to sleep on the floor overnight, as well as asylum seekers who were turned away from shelters and forced to sleep on the street. Others, she said, had fled shelters out of fear for their safety. All of this, said Phillips, “really exposed the extent to which the system is violating basic human rights principles.”

Mayor Eric Adams, who has said the system is “nearing its breaking point,” has found himself caught between these critiques and the larger national debate over immigration. In recent months, asylum seekers have been sent to New York, Washington, D.C., and other Democrat-led cities, courtesy of Greg Abbott, the Republican governor of Texas, and more recently, Florida's Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis.

Both men are immigration hawks and opponents of President Joe Biden’s immigration policies, and are also considered possible rivals for the Republican nomination for president in 2024.

Together, they have helped shift the discussion over border issues from the Southern states to Northern cities, and prompted some sharp critiques of the shelter system in New York City, which is obliged under state law to provide for all those seeking shelter.

For his part, Adams has decried the people-shifting work of the Texas and Florida governors, while imploring Washington to send more help. On Thursday, his administration announced plans to support the new arrivals by opening “Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Centers,” for which details were still being worked out.

“This is an American crisis that we need to face,” Adams said on ABC's “This Week.”

The path forward

The challenge for Gonzalez and the others going forward will be to successfully pursue their asylum claims. His is based upon his involvement in political protests.

“In our country we are attacked by the government,” said Gonzalez.

A report released on Sept. 20 by the UN Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela found that “the Venezuelan state relies on the intelligence services and its agents to repress dissent in the country.”

One arm of the government, SEBIN, was found to have “tortured or otherwise ill-treated detainees — including opposition politicians, journalists, protesters, and human rights defenders.”

This comes amid a massive exodus, which is “the largest migration crisis in recent Latin American history” according to Human Rights Watch. As many as 6.8 million people have left Venezuela since 2014.

The key to all these cases is the credibility of the individuals testifying.

Steven Schulman, Akin Gump attorney

While many have left for nearby countries, the struggle to obtain work abroad during COVID-19 shutdowns prompted 130,000 Venezuelans to return to their country, but Human Rights Watch found that “returnees are subject to abuse upon arrival.”

Still, legal experts said Gonzalez and others seeking asylum in the U.S. face a system that is tremendously backlogged and often skeptical of asylum claims, which must show that the individual is part of a persecuted group.

“An economic crisis is not grounds for asylum, nor is civil strife,” said Steven Schulman, an attorney with Akin Gump who has handled dozens of pro bono asylum cases.

In the absence of witnesses who represent the government, Schulman said, immigration courts rely heavily on statements from the asylee.

“The key to all these cases,” said Schulman, “is the credibility of the individuals testifying.”

Asylum applicants face different outcomes depending on where their appeal is heard. While New York immigration judges approve 82% of asylum applications, the figure is only 17% for judges in Houston, 33% in Dallas, and 43% in San Antonio.

But even an exhaustively prepared asylum application may not receive a fair hearing, said Pertinderjit Hora, an immigration attorney who has clients in New York, Indiana, and Georgia.

“There's skepticism around the stories that are being heard in court,” Hora said. “And some of them are not even being read. It's not humanly possible to keep up.”

The pile-up of cases meant that an asylum application could take years.

“We have clients that wait four, five, six years for an asylum hearing,” said Schulman.

Gonzalez is mindful of employment.

He will need to obtain a work authorization. Although he initially said he’d take whatever work he could get – construction, or sales in a store ideally – in a follow-up interview he declined any questions about work.

Hora said that in her experience, immigration judges did not penalize asylum applicants if it was clear they’d worked before they were legally allowed to, reasoning that it was a necessity.

“No judges ever said anything,” said Hora. “No asylum officer.”

What judges do care about, she said, is something known as “good moral character,” or GMC for short. She advises her clients to pay their taxes in order to establish their GMC. In lieu of having a Social Security number, some immigrants do so through use of an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number.

For Gonzalez and others arriving in the U.S., Hora said obtaining work, lawful or not, is not challenging.

“Employers are getting desperate,” she said. “They need someone to hire right now.”

Although Gonzalez is tight-lipped about his job prospects, he’s clear about his obligations.

“Everything in our country is really bad,” he said, and his hope is that he can help his family back home.

That includes his youngest daughter, who is about to turn 11 and whose name is tattooed on his upper arm. He asks her to be patient, reminding her that “everything is a process, so I'm going through the process.”

The Darien Gap

Gonzalez’s journey to the U.S. took two months, and involved seven or eight days traversing the Darien Gap, a notoriously dangerous stretch of Colombia and Panama, where many travelers have succumbed to the rough terrain or violence.

“It’s the most dangerous jungle in the world,” Gonzalez said, citing the lawlessness as well as the crocodiles, venomous snakes, and other wild animals.

During this time, the trio rarely slept, his nephew said, relying on the sugar rush from a constant supply of sweets and candies to stay alert. He was especially concerned for the safety of his girlfriend. They declined to be identified in this story for fear of jeopardizing their asylum claims.

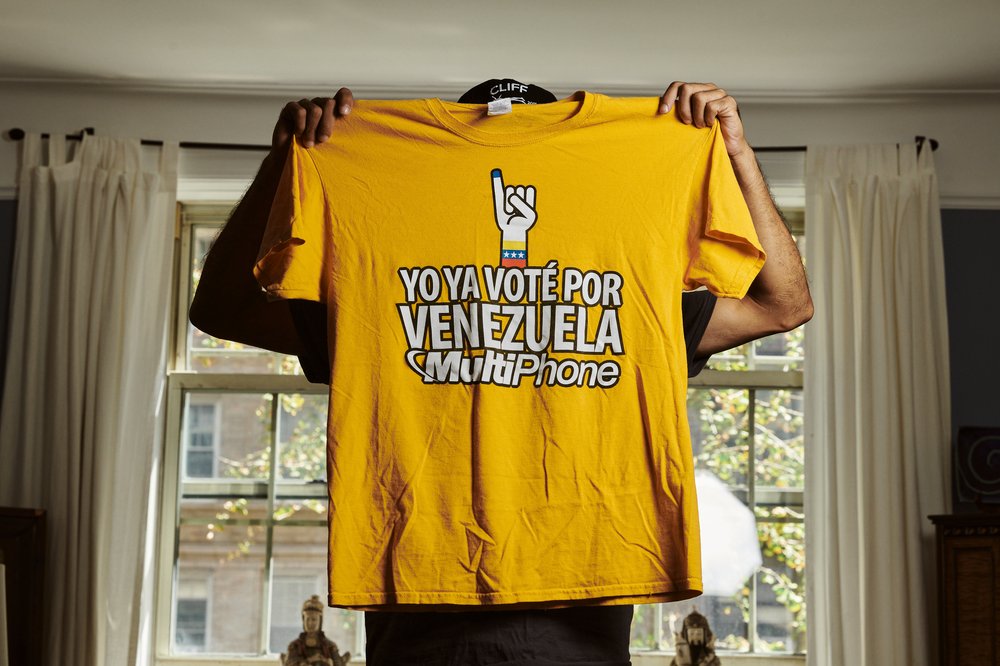

The young woman said she’d left high school at the age of 16 due to Venezuela's economic crisis, which caused the country's economy to contract by 80%, pushed its inflation to the highest levels in the world, and rendered its currency almost worthless, with government workers earning the equivalent of $1.50 per month. She spent much of the last five years outside of Venezuela, working at various jobs including a restaurant in Peru and a cell phone store in Colombia.

“I came to this country because of the economy,” she said, “to get a better future for myself and my family.”

Her boyfriend had his own problems. He was the oldest of four brothers and wanted to help his mother, whose health had declined, but his part-time job at a store only brought in $10 a week.

None of the three has given much thought to the forces aligned against their arrival and other asylum seekers – including DeSantis’ allegedly luring other migrants onto a private plane in San Antonio and flying them to Martha’s Vineyard. A class-action lawsuit claims the migrants were “fraudulently induced to travel across state lines by DeSantis and the state of Florida.”

“I was just thinking about my family,” Gonzalez said of the thinking behind his decision to flee Venezuela, “and we just took the decision to leave.”

A host who helps

Gonzalez and his two younger companions had initially intended to stay in a New York City shelter, but discovered they wouldn’t be able to live together because they didn’t have the needed documents to prove they were a family. The idea of Gonzalez and his nephew in one shelter and his nephew’s girlfriend in another didn’t sit well with the group.

“We came together, so we wanted to stay together,” Gonzalez said.

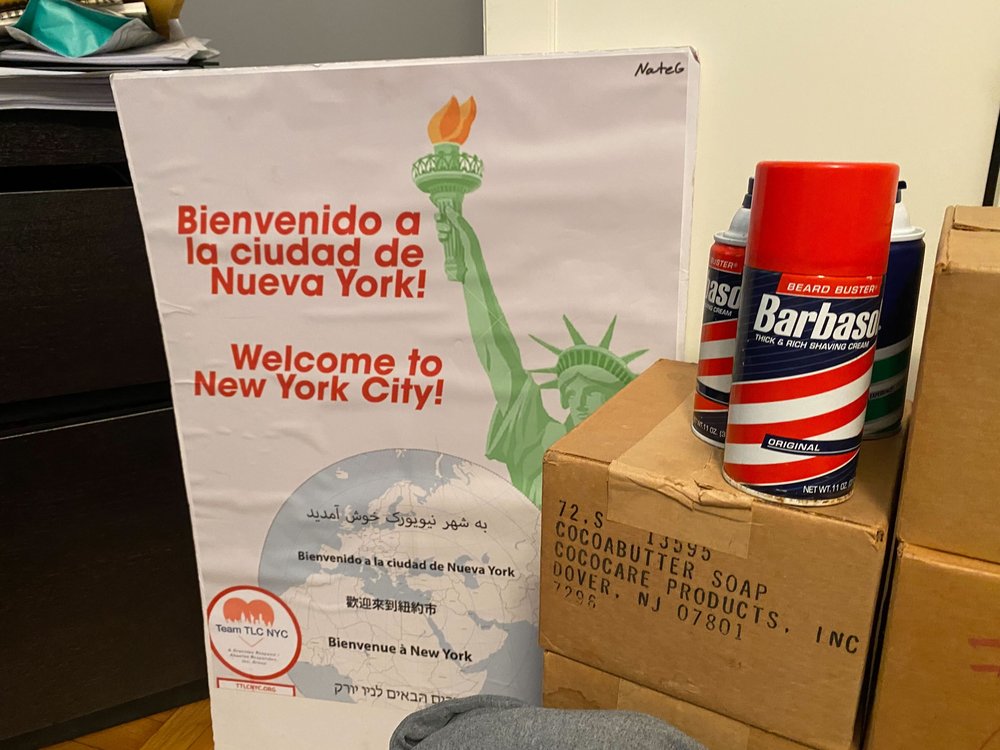

It was at that moment that Ilze Thielmann, the director of volunteer group Team TLC, received a call from a fellow volunteer. She and other New Yorkers had spent the previous weeks receiving busloads of asylum seekers and trying to help them feel welcome in a strange new city.

Thielmann soon grasped the nature of the situation and made a decision: If the two men and a woman weren’t allowed to stay together in one shelter, she’d invite them to live in her home. It wouldn’t be her first time, either: a few years earlier, she and her attorney husband had hosted an asylum seeker from Honduras.

This was something she learned growing up, Thielmann said, as her mother and stepfather also opened their home to people in need.

“There are numerous people who lived with my parents for months or years at a time,” Thielmann said. “And that example was set very early on in my life.”

In time, Thielmann would become a corporate litigator, first defending corporations in class-action lawsuits, then suing insurance companies on behalf of patients and health care providers. She retired at the age of 50, and is thankful to now have a “nice home, and to not have to worry.”

“So with that luxury,” she said, “I feel like I have a responsibility to help people who do have to worry.”

It helps that their home is far more spacious than the typical city apartment.

Gonzalez’s room, she noted, was what earlier building tenants called “the maid’s quarters,” and in addition to their current guests, they were expecting another houseguest, the son of a friend. He’d be staying in a spacious area that was once designated the dining room but now functions as Thielmann's office and a holding area for donations Team TLC received for asylum seekers:, such as clothes, baby shoes, sanitary pads, and canisters of shaving cream.

“We have lots of room, you know, so why not? Why not share?” she asked.

As for the subtler, often more complicated task of not getting on each other’s nerves, Thielmann said the asylum seekers were “very independent” and “come and go as they please.”

“They don't need to be underfoot and they don't need me to be hovering over them,” she said, “which is great, because I don't have time to hover over anybody right now.”

I had to walk for almost two months through heavy rain, sleeping in the street, eating in the street.

Gonzalez, asylum seeker from Venezuela

They also have free rein in the kitchen and buy groceries with cash Thielmann provides. Gonzalez said he enjoys making arepas and pasta, and on a recent evening Thielmann said they offered her what seemed to be a delicious pork loin preparation, which she had to decline because she was too tired from having awoken at 4:30 a.m. that day to greet new asylum seekers at the Port Authority.

Thielmann also cooks for her guests, as Gonzalez’s nephew and his girlfriend were finishing a breakfast of scrambled eggs prepared by their host when a reporter appeared at the home.

For Gonzalez, the situation is not something he takes for granted.

“I had to walk for almost two months through heavy rain, sleeping in the street, eating in the street,” he said, recounting his journey from Venezuela to the U.S. border.

“I feel like a king,” he said. And for this, he gives thanks to Thielmann and to God.

But there are other helpers.

A visit from a fellow asylum seeker

One day after arriving, the three received a visit from another immigrant. Rafael Suarez, 25, had come to the U.S. in 2019 from Honduras, and, like the newcomers, he had also been hosted by Thielmann. Back then, he was recovering from his time at the Port Isabel Detention Center in Texas, where he spent three months.

“Those were the worst days of my life,” he said via text message.

His luck changed after arriving in New York and receiving a room in the Thielmann home. His first job was washing dishes in a restaurant, he said, and in 2020 he received his work permit and social security number. Meanwhile, he pursued a claim of asylum.

His application was based on the threat he faced in Honduras as a gay man, a problem that has been widely documented. One Honduran human rights group noted earlier this year that 405 LGBTQ Hondurans have been killed since 2009, and a report by Human Rights Watch noted that many LGBTQ asylum seekers arriving at the southern border “reported serious abuses in their countries of origin, including rape, assault, death threats, extortion, and forced disappearances or killings of romantic partners and friends.”

Against that violent backdrop, Suarez's asylum claim was approved on Dec. 21, 2021. He remembers the exact time when his life was altered: 11:39 a.m.

“The judge told me: ‘Sir, you have been granted asylum.’”

That moment, he said, was transformative, allowing him to become gainfully employed while sending money back to his mother. Today, he works at a factory in Astoria, baking cookies for a baker whose outlets are in Manhattan. The oatmeal raisin cookies, he said, are his favorite.

More importantly, he’s able to inhabit his identity without fear of persecution.

“What really changed my life is being in this city so FREE and being able to be the way I am,” he wrote, using all caps to emphasize the word LIBRE in Spanish.

His advice for these newcomers was simple.

“I told them, welcome to this beautiful country and that they have to rest one day and the next day look for a job in order to get ahead.”