Families of Rikers detainees who die in custody say they’re often left in the dark

April 9, 2025, 6 a.m.

It can take weeks or months to get answers about their loved ones’ final days.

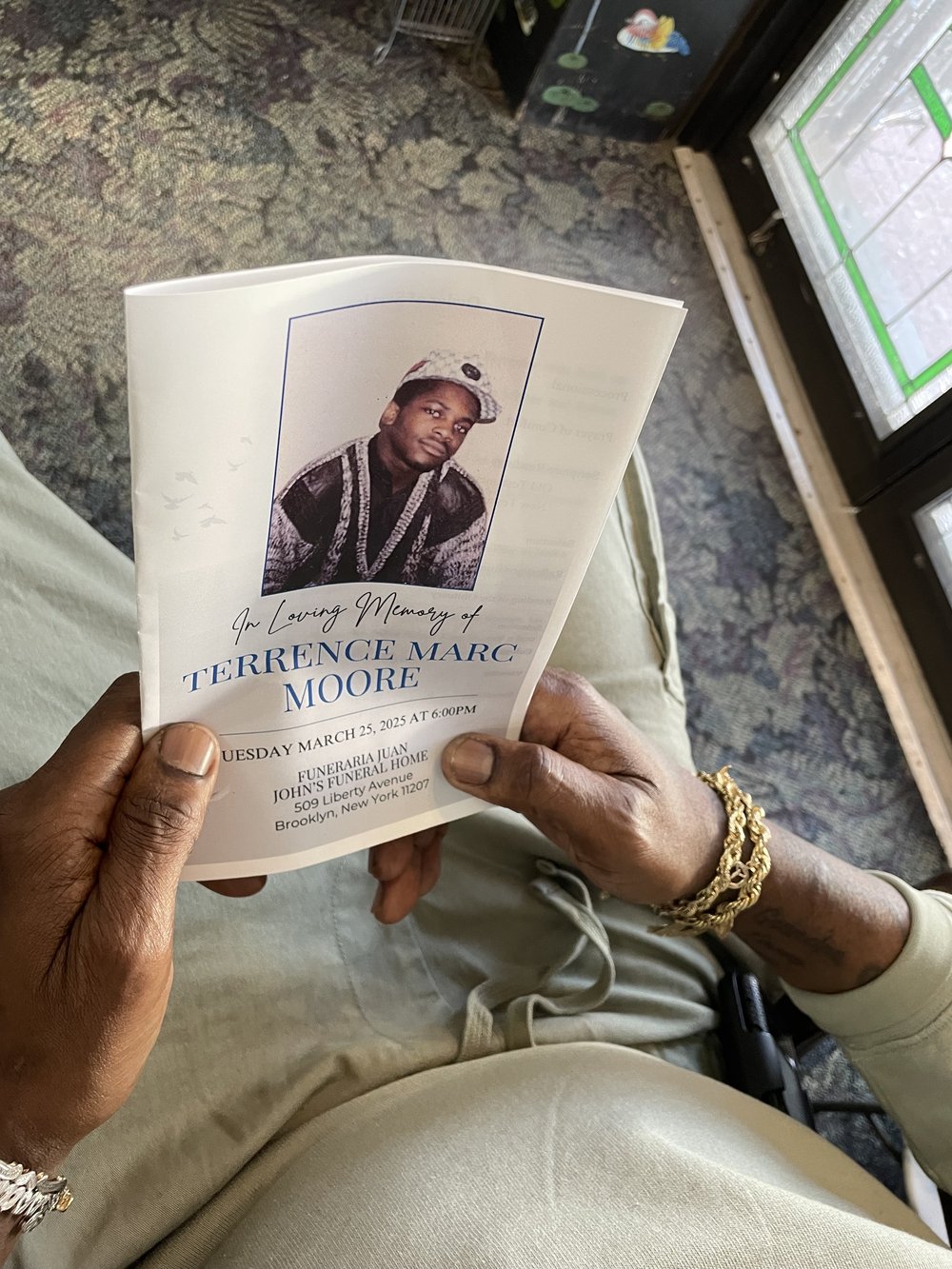

Terrence Moore’s funeral looked like an ordinary ceremony: Family members and friends streamed in and out of the funeral home in East New York as he lay in a casket at the front of the dimly lit room, dressed in a crisp white shirt and tie.

But his loved ones were missing crucial information that most mourners take for granted: They did not know how he died.

The 55-year-old was one of five people since mid-February who have died in or shortly after being released from the custody of New York City’s Department of Correction, according to authorities. In several cases, detainees’ relatives said they have struggled to get consistent information from the department about what exactly happened to their loved one in their final hours.

“I don't know what it was [that] killed my husband,” Moore’s fiancée Nickesha David said through tears at the funeral. “Whatever they did, they f—ed up.”

Moore was found unresponsive in a holding pen at the Manhattan Criminal Courthouse on Feb. 24 and was pronounced dead after correction and emergency medical workers rendered aid, a city watchdog report found. His death remains under investigation more than a month later, leaving his family without closure or answers, and his legal case unresolved.

The Board of Correction, which oversees the Rikers Island jails, conducts interviews and reviews jail records to compile death reports describing what other detainees witnessed, how correction officers acted, surveillance footage and whether any contraband was discovered in the detainee’s cell. The reports do not initially include autopsy results on a cause of death; those are handled by the city’s chief medical examiner and can take a few months to be completed.

Obtaining clear details, though, is often so onerous that some families look to outside attorneys and advocates for help while planning funerals, handling estates and grieving.

Shayla Mulzac-Warner, a Department of Correction spokesperson, declined to comment on any pending investigations, but said officials work quickly to notify next of kin when someone dies in custody.

"When a next of kin is not listed, our investigators use other methods to track down loved ones," she said in a statement. "That information is then shared with our Chaplaincy Division, who then notifies the family in person. Every death is a tragedy, and we extend our deepest condolences to those who have lost loved ones."

According to Marc Bullaro, a former assistant deputy warden who worked at Rikers for 29 years, the process is not always straightforward.

“ Sometimes the people in custody, they give a wrong address, they give a wrong phone number,” he said. “And then they have to go through the attorney and hopefully the attorney knows the correct information. So a lot of this is not the fault of DOC.”

On the day he died, Moore was at the Manhattan courthouse for an appearance related to the 2023 murder of an Upper West Side woman, according to his lawyer Glenn Hardy. But Hardy said he waived Moore’s appearance, so his client, who was due for a psychiatric evaluation in the case, never saw the judge.

That afternoon, the attorney got a call from the Department of Correction, informing him that Moore had been found unresponsive and was dead.

Hardy, who represented Moore for two years, said he was shocked by the news. “He didn’t complain about anything or say, ‘Hey, I need medication,’ other than complaining about the food [at Rikers],” he recalled in February.

In a statement that night, jail officials said Moore had had a seizure. But a Board of Correction report on his death, dated Feb. 28, said he became lethargic and started vomiting in the courthouse holding area after smoking some kind of drug. Jail staff responded and administered chest compressions, CPR and Narcan, an antidote for opioid overdoses, before calling paramedics, according to the report.

Moore’s family members pushed back on the medical explanations provided by officials, saying they never knew him to have seizures or use drugs. His brother Kerry Moore said that even if Terrence had used drugs, correction staff were responsible for keeping illicit substances away from detainees.

“Who was monitoring that situation?” Kerry said. “DOC has a duty to make sure everyone who walks in[to] their custody come[s] out the same way they walked in.”

In the Feb. 19 death of Ramel Powell, 38, surveillance video captured “multiple individuals” crowding around and moving him unconscious between Rikers cells the night before, according to a watchdog report. Staff discovered him unresponsive in his cell hours later, and the officer on duty was suspended for failing to render aid or declare a medical emergency immediately after noticing he was in distress, the report said. It made no conclusions about how Powell died.

The families of the three other detainees said they encountered similar obstacles in trying to understand how their relatives perished in city custody.

It took Ariel Quidone’s mother and sister days to learn he had died from apparent untreated appendicitis on March 15, barely a week after he was jailed on robbery charges. Quidone’s family, which has hired an attorney to search for answers, said he was healthy when he arrived at Rikers. Jail officials said they brought him to Elmhurst Hospital in Queens once he became ill, and a judge released him from custody the day before he died.

His death report found the correction department did not notify his family because he was no longer in custody. Video footage showed he “did not appear to regain consciousness” after Rikers staff tried to resuscitate him in his cell.

Edward Jenkins told Gothamist he was also going to hire a lawyer to look into the March 31 death of his brother, Dashawn Jenkins, who was observed “visibly ill” in his Rikers cell and died 45 minutes later, according to jail officials.

“They’re saying his heart stopped,” Edward said. “He’s a healthy kid, 27 years old.”

The death of 54-year-old Sonia Reyes on March 20 is still under investigation as well. Her son told the New York Daily News he did not believe she had died by suicide. Her death report lays out a basic timeline of correction officers' interactions with her in the hours before she died, but a description of her condition when personnel found her unresponsive in her cell is redacted from the version of the document obtained by Gothamist.

The death toll for 2025 puts Rikers on track to exceed the five detainee deaths in all of last year, according to Board of Correction figures. The jail complex, which recorded a 25-year high of 19 detainee deaths in 2022, faces the possibility of a judge-ordered takeover in a federal case.

The City Council is currently considering a bill to promote transparency from the Department of Correction by establishing reporting requirements for detainee deaths, along with a “jail death review board” to examine any systemic issues. In testimony before the Council last September, jail officials said they had “significant concerns” about the proposals, citing “on-the-ground realities, best practices, [and] due process.” Councilmember Lincoln Restler, who introduced the bill, said it would provide relatives crucial information in a timely manner.

Bullaro, the former correction official, said Rikers’ biggest problem was an environment of lawlessness and violence, which he said contributes to more deaths.

“The department is using most of their resources just to keep their head above water … to quell these fights … instead of to take care of the people in custody,” he said.

This story has been updated with additional information.

NYC keeping people with mental illness on Rikers Island due to hospital bed shortage Another death in custody at Rikers, officials said — jail on track to outpace last year After another death at Rikers, family says it's struggling to get answers