Erosion is causing ‘extremely hazardous’ conditions on Riis Beach, where 2 teens were swept to sea

June 26, 2024, 11:51 a.m.

Erosion is rapidly washing away the shoreline of Jacob Riis Park in Rockaway — and the National Park Service says the ongoing problem has created dangerous swimming conditions in an area of the beach where two teen boys were swept out to sea last week.

Erosion is rapidly washing away the shoreline of Jacob Riis Park in Rockaway — and the National Park Service says the ongoing problem has created “extremely hazardous” swimming conditions in an area of the beach where two teenage boys were swept out to sea last week.

The “People’s Beach,” which has been run by the federal government since 1974, has dwindled for years. Last summer, the Army Corps of Engineers spent $12 million to dump 360,000 cubic yards of sand in an effort to replenish the area. But much of it washed away in the winter and spring, exposing unsafe “deteriorating wooden groins, rockwork, and other structures,” the National Park Service wrote in a news release last month.

Experts say rapid erosion on shorelines disrupts currents, creating the dangerous conditions the boys faced before they disappeared into the water. The Army Corps’ ongoing work to build new jetties and bolster the shoreline along the city-owned Rockaway beaches farther east contributed, at least in part, to the quick disappearance of sand at Riis Beach, according to agency spokesperson Hector Mosely.

John Fletemeyer, the chair of the International Drowning Prevention Alliance, said dangerous currents are more common around jetties, like the one made of boulders that separates Riis Beach from the city-owned waterfront. The Army Corps recently rebuilt the jetty, work Fletemeyer said can affect currents.

“There’s a good chance that if you change those dynamics, you’re going to increase or decrease the likelihood of a rip current,” said Fletemeyer. “Typically by jetties, groins and piers, those are areas where you find rip currents.”

The problem at Riis has already forced officials to close off sections of the beachfront to swimmers, and the National Park Service expects they will remain shut for the entire summer.

The entire Rockaway shoreline was closed to swimming on Friday at the time when the boys, ages 16 and 17, were swept away. The NYPD says they jumped in the water around 6:30 p.m., 30 minutes after lifeguards clock out along the entire peninsula. High tide was roughly two hours away.

“The teens tried to jump up to kind of slice the wave. The wave was extremely high, and it went on top of them and sucked them over,” NYPD Deputy Commissioner of Operations Kaz Daughtry told reporters.

Divers who were searching for the boys that evening had to retreat from the rough surf for their own safety, according to Daughtry. On Tuesday, the NYPD said the search had been called off without finding the bodies.

A paradise lost

Riis Beach stretches over a mile along the Rockaway peninsula's western side. It was built by the city under the direction of Robert Moses in the 1930s.

Moses modeled the park after his beloved Jones Beach out on Long Island. The federal government took over Jacob Riis Park during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s. Hurricane Sandy slammed the entire Rockaway shoreline in 2012, and the once-gleaming recreational area’s buildings and shoreline have since deteriorated.

Every summer, the beach attracts a dedicated cohort of swimmers and sunbathers, like Samir Arboleda, who spends as much as two hours on public transit from Washington Heights to get there.

Arboleda said the sand dumped by the federal government last year extended the beach and gave visitors more room — but added that he was shocked by how much the shoreline shrunk during the off season.

“Last year you literally had to walk, it felt like a mile, just to get to the ocean. It was leveled, it was like a brand new beach. It was crispy clean, the sand was pretty,” said Arboleda, who has spent his summer days at Jacob Riis for 19 years.

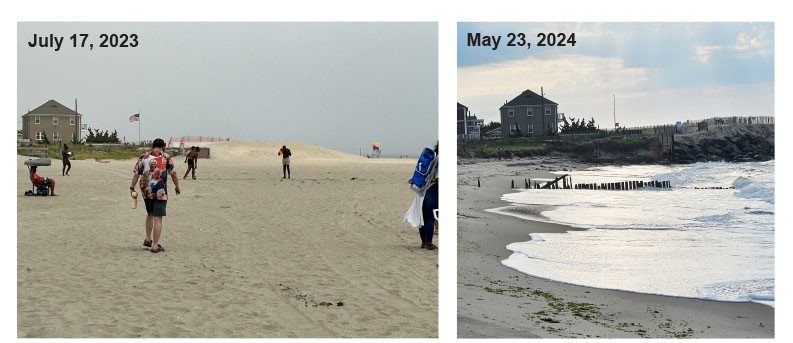

Images published by the National Park Service capture the striking change. The beach has shrunk more than 20 feet since last summer.

“All that was dunes. It was really pretty. All that is gone,” Arboleda said, pointing to the rock jetty that divides the federally owned Riis Park from the city-owned Rockaway beaches to the east.

Mosley, the Army Corps spokesperson, said the work to restore the rock jetty “can cause the natural movement of eroded sand” away from Riis Beach. The Army Corps project — which began four years ago and is slated to run through 2026 — has built or restored other jetties and added new sand dunes throughout the city-owned Rockaway beaches.

Aside from the sand that’s washed away since last summer, Riis Beach hasn’t received the same treatment as its eastern neighbors. Riis is located in a federal park, while the other Rockaway beaches occupy city land in front of residential neighborhoods.

Mosley said the Army Corps could build new jetties — or “groins” — to protect Riis Beach, but only if the National Park Service requested them.

Rob Young, the director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University, said the resiliency work on the city-owned beaches is exacerbating the erosion at Riis.

“The groins (jetties) are there to stop the sand from moving down the beach,” said Young. “Wherever the last groin is, that’s where you have problems. There’s no doubt that the increased erosion that’s at the end of the pipe there, Jacob Riis, and going out to Breezy Point, is a result of the fact that we’re trying to hold all the sand in up the beach.”

“Groins are helpful on one side of the groin, but then they cause a problem on the other side of the groin,” he added.

Young said roughly 40 million cubic yards of sand has been dumped at Rockaway since 1930, and questioned whether the beachfront could be sustained decades into the future as sea levels continue to rise due to climate change.

NYPD officials last week said they believed a strong current swept away the two teens who went missing in the waters last Friday. And the National Weather Service on Tuesday warned swimmers at the beach faced a higher risk of encountering dangerous rip currents.

“We’re going to be cautious for the most part,” Brooklynite Tiffany Tucker said as she walked up to the beach on Monday with two young children. “We’re just coming out here to get out the house a little, but we’re going to be very cautious.”

Parts of Rockaway Beach will remain closed during ongoing Army Corps project