Episcopal Diocese of New York set to apologize for the church's role in slavery

March 23, 2023, 1:31 p.m.

The apology is decades, if not centuries, in the making. Earlier, the church established a fund for reparations.

The Episcopal Diocese of New York announced that it intends to issue a formal apology on Saturday for the “participation and complicity of the diocese” in the transatlantic slave trade and its “continuing aftermath and consequences.”

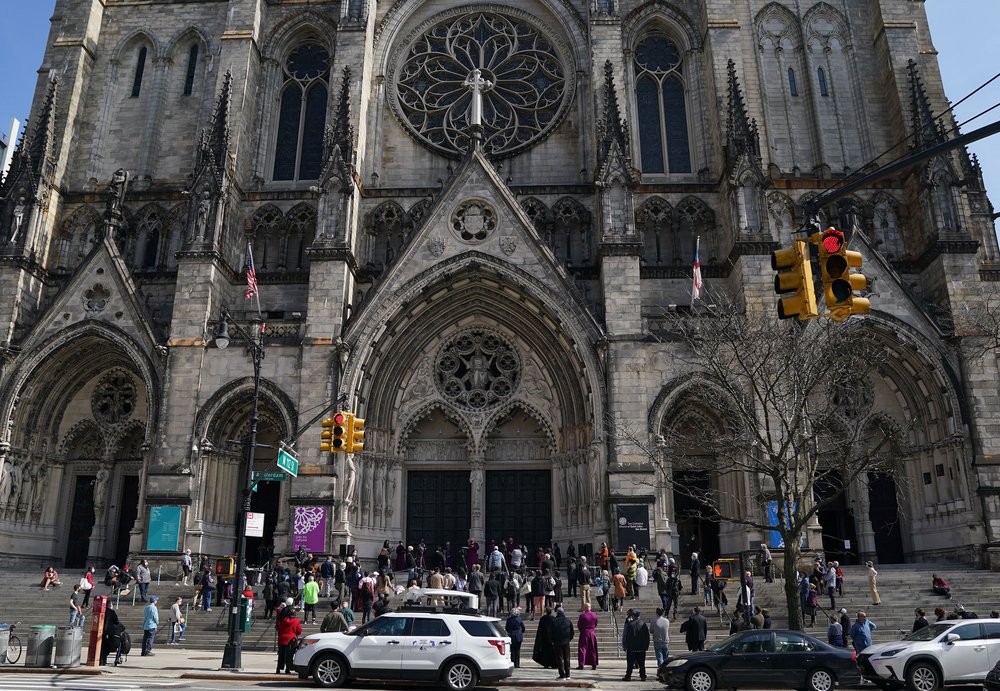

The “Service of Apology for Slavery” is set to take place during a ceremony at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in Upper Manhattan and follows a process through which every parish in the diocese was asked to investigate connections to slavery, said the Right Rev. Andrew M.L. Dietsche, bishop of the New York diocese.

“The complicity that we identify in our diocese had everything to do with the labors of enslaved people and the money built by the slave trade, in establishing and building our churches,” Dietsche said in an interview with Gothamist. “This is where our complicity is and this is what we're apologizing for on Saturday.”

The complicity that we identify in our diocese had everything to do with the labors of enslaved people and the money built by the slave trade, in establishing and building our churches. This is where our complicity is and this is what we're apologizing for on Saturday.”

The Right Rev. Andrew M.L. Dietsche, bishop of the New York diocese

The apology is decades, if not centuries, in the making. A resolution adopted by the Episcopalians’ national leadership at its 2006 General Convention called slavery a “sin” and a betrayal of the “humanity of all persons.” It called on churches to study how they had benefited from slavery.

The Episcopal Diocese of New York has been out front in this inquiry. In 2019, Dietsche asked the diocese to set aside $1.1 million from the endowment of the diocese as “seed money” for a future reparations project. That year, he said, it represented 2.5% of the endowment. He added at the time: “The Diocese of New York played a significant and genuinely evil part in American slavery.” He added: “We must make, where we can, repair.”

Dietsche said Wednesday that discussions are still underway about specific forms of reparations, but that talks so far have centered on providing college scholarships as well as health care and housing, along with clearing institutional obstacles that have prevented African Americans in the church from working at “high-profile parishes and dioceses.”

The diocese comprises 184 parishes spread across Manhattan, Staten Island and the Bronx, as well as Westchester, Dutchess, Orange and other suburban counties. There are 1.6 million members of the U.S. Episcopal Church and 77 million worldwide in what’s known as the Anglican Communion.

A reparations task force

Cynthia R. Copeland, a public historian and Episcopalian who has served as co-chair of the Reparations Commission of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, said the apology was significant given the Episcopal Church's stature and its centrality to history, power and wealth in New York since the 1600s.

“This is the descendant of the Church of England that gets started in New York City and has a lot of the original folks who started the various churches, the Trinity Wall Street Church, St. George's,” said Copeland. “These were individuals who were or associated with founding fathers,” including George Washington, who went to St. Paul’s Chapel immediately after his inauguration in 1789.

The planned apology is the culmination of internal discussions that began in 2006, according to church officials, as well as the work of a reparations task force. At a church convention in October, parishioners watched a video that brought together historians as well as Black and white officials.

In the video, a Black member of the diocese and longtime civil rights activist, Nell Gibson, recounted a church meeting years ago, where a white parishioner admitted that he was transformed by a presentation by a diocesan archivist, explaining the church’s complicity in the slave trade.

“He at the end said, ‘I believe now that some atonement and some repair is due,’” Gibson recounted. “I was almost in tears listening to him.”

Diane Pollard, who is Black and one of the original members of the diocese's reparations commission, said the process had been challenging but that it was “done with substance.”

‘The apology is not the end’

“On a personal level, it's been a long journey and I am happy that we are having this event on Saturday,” said Pollard, adding, “The apology is not the end. The apology is the beginning.”

Dietsche said one of his own revelations about the church’s deep roots in human enslavement took place during a visit to an Episcopal church: St. Augustine’s Church on the Lower East Side.

The church, said Dietsche, still has “slave galleries” upstairs where the men and women enslaved by congregants sat on “very, very low risers” while their owners sat in pews on the ground floor or in separate balconies.

“You have every message given to you that you are on the outside, you are not included, you are not an equal to the people who are sitting in the balcony and in the pews,” he said.

In recent years, he said, all parishes throughout the diocese were tasked with looking into their archives and uncovering the depths of human enslavement.

Parishes owned slaves

“We discovered that we had parishes that as a parish owned slaves, we discovered that so much of the wealth of the Diocese of New York came out of the shipping industry and as late as 1860, The London Times declared New York Harbor to be the No. 1 slave market in the world. Long after the state of New York had eliminated slave ownership, we were still up to our ears in the slave trade,” Dietsche said.

Copeland said it’s likely some Black Episcopalians would not accept the church’s apology, having directly “felt the wrath of white Episcopalians within the churches” or experienced microaggressions over the years.

“You can't erase 400-plus years of this kind of cruelty that has been embedded in this institution of the Episcopal diocese, but also in our society in general,” said Copeland, who serves as president of the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History.

Despite the expected hurdles, Copeland said it’s crucial for the diocese to stay the course, “in order to get to this place called Beloved Community, which is really what we're striving for.”

The service will include a video address by the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, the Most Rev. Michael B. Curry, and be livestreamed on the website of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine.

‘It’s like a public dump.’ How the remains of formerly enslaved people came to rest beneath a Staten Island strip mall New report shines spotlight on enduring stain of slavery in NY A virtual tour of NYC Black history – through the corridors of City Hall