A decade after Sandy, volunteer historians restore a Queens neighborhood's lost memories

Oct. 6, 2022, 6:01 a.m.

The Breezy Point Historical Society was created from the storm’s wreckage to preserve photos, newspapers, and even a long-lost film of Jackie Robinson.

It all started with an old film reel of Jackie Robinson, found in the wreckage of a Breezy Point house a couple of days after 350 other homes were leveled by floods and fire in a single night during Hurricane Sandy.

On a top shelf, untouched by the floodwaters from the 9-foot-high storm surge, Paul Balukas reached his hand into the back of a closet and found an old peanut tin — full of about 20 round, gray metal Super 16 mm film canisters — heavy with the acrid scent of nitrate.

They belonged to homeowner and widow Doris Neimeth, who is now 85. She was in Florida with her husband Albert when Sandy hit and she got the news that her home, which was passed down through Albert's mother, was lying on its side with most of its furniture and appliances washed away.

“When the ocean met the bay, it knocked my house off its foundation,” Neimeth said. Her home was already built up on cinder blocks about 6 feet off the ground. “When we went to see it, it was on an angle, a tilt, and the deck was gone.”

She told Balukas to take whatever he could salvage from the remains of her house for Christ Community Church, where he was president for many years.

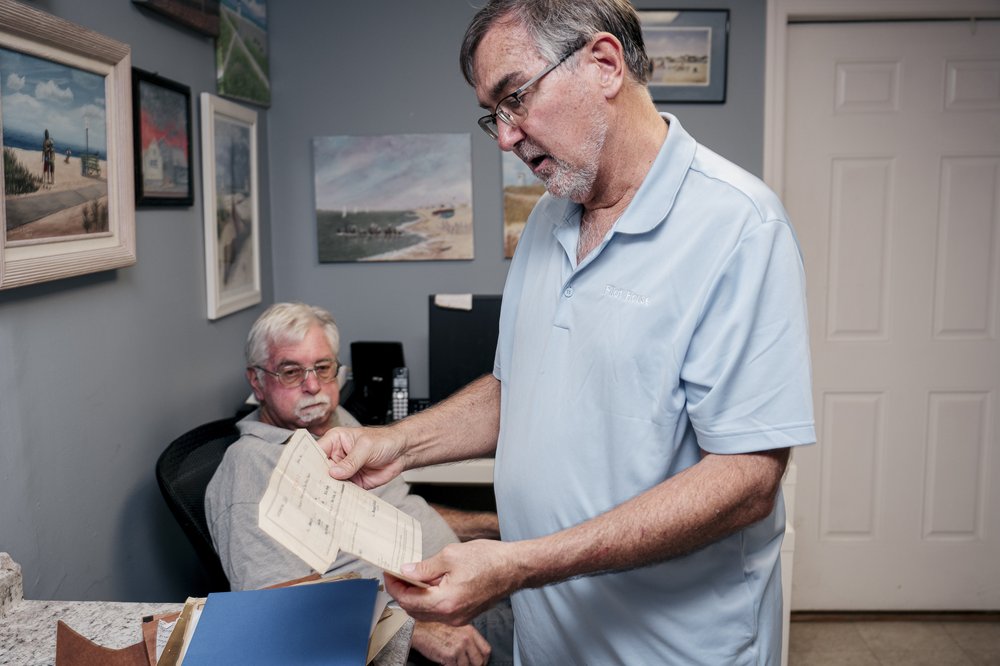

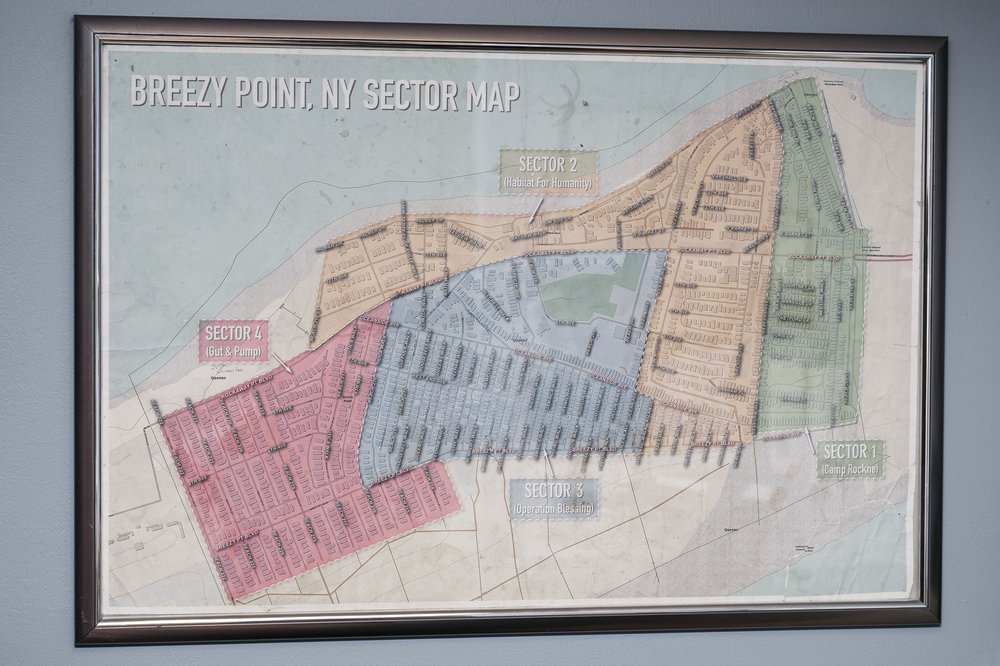

From what seemed destined for the dumpster came the seeds of the Breezy Point Historical Society, an organization with a mission to make the tight-knit Queens community’s memories more resilient to future storms by preserving them. Ten years after the storm, the 500-acre beach cooperative of mostly city workers continues to provide a daily stream of local artifacts for consideration in the society’s collection — as well as financial support since the organization became officially chartered in 2015. The organization is run by 18 dedicated volunteers, mostly current and former board members, who are supported by the group’s 150 members.

The society offers a blueprint for preserving local memories for countless coastal neighborhoods due to be hit by intensifying storms as climate change worsens.

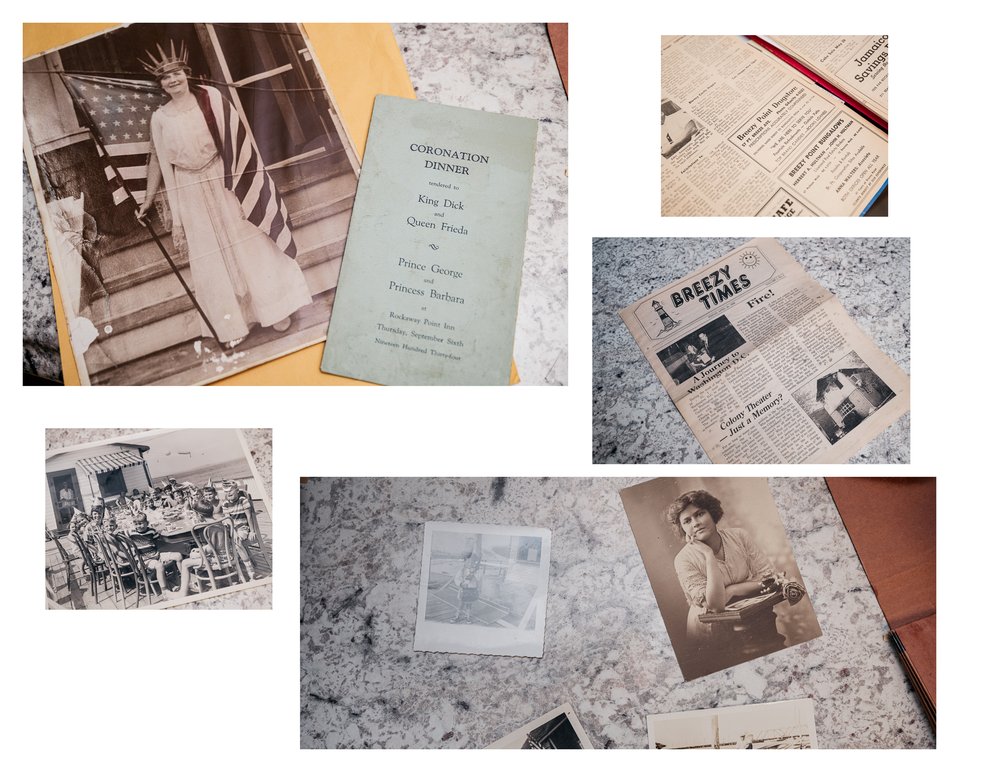

Its organizers have created a collection of objects rescued from Hurricane Sandy. Yellowed family photo albums and tattered old newspaper clippings are digitized in their archives for safekeeping — and a way for residents to rebuild their own lost family histories by providing a communal repository where one might find a great-grandfather’s business ad above an old news story or a baby picture of a favorite aunt from a neighbor’s barbecue.

More than a century’s worth of bric-a-brac threatens to burst from the member-funded office space located on the side of a medical center at 204-08 Rockaway Point Boulevard.

“We realized that many, many people lost all their photos, their videos, the whole history of their life here in Breezy Point,” Balukas said. “We decided we had to do something to make sure that never, never happens again."

Residents come to the office located on the quiet main drag and spend hours sifting through the photo archives of more than 5,000 images just to find a photo of a deceased parent or what their home looked like 40 years ago, before it was rebuilt and raised as a result of damage from Hurricane Sandy.

At first glance of Doris Neimeth’s house, there seemed not much left for taking, but Balukas was curious about the forgotten reels.

“As I was leaving I saw a closet upstairs and sure enough, there was about 20 rolls of movie film – just totally forgotten about,” Balukas said. “They were amazing. There were films of Breezy Point back from the ‘20s and the ‘30s of the ocean of the old homes.”

When the 1950s footage included Albert Neimeth at the Brooklyn Dodgers' spring training, working on his pitch alongside baseball legend Jackie Robinson, Balukas decided to share the home movies with the community, which was hungry to connect with its past after Hurricane Sandy wiped away generations of memories.

'Flood, fire, and a superstorm'

On Oct. 29, 2012, at approximately 6 p.m., Marty Ingram, 63 at the time and chief of the volunteer-run Point Breeze Fire Department, was sitting down with his crew for dinner when one of them saw the tide coming in strong.

“The seagulls will tell you everything — where the fish are and they'll tell you what the weather's gonna do,” Ingram said. “If you see the seagulls flying across the bay to the mainland, it's gonna be really bad. And that's what I saw that night, and it scared the heck out of all of us.”

Ingram saw storm surges breach both sides of the narrow peninsula — a strip of earth less than a mile wide that is wedged between the Rockaway Inlet, Jamaica Bay, and the Atlantic Ocean.

The subsequent contact between sea water and electricity started a fire that engulfed a roughly 10-acre patch of 135 houses. The wind urged the blaze to quickly spread among the houses, which were closely packed together like eggs in a carton.

The remnants of Breezy Point after fires sparked by Hurricane Sandy ravaged the Queens neighborhood.

The residential streets were narrow sidewalks meant only for pedestrian traffic, and with houses burning on both sides, it was difficult for Ingram's 15-member volunteer crew to breathe, see, or move around. Ingram called it a “cave of fire.” Around dawn, the six-alarm fire was under control after firefighters from across the city joined to battle the flames overnight.

“Every single home down here had some nature of damage,” said Arthur Lighthall, general manager of the cooperative at the time of Hurricane Sandy and the treasurer of the Breezy Point Historical Society.

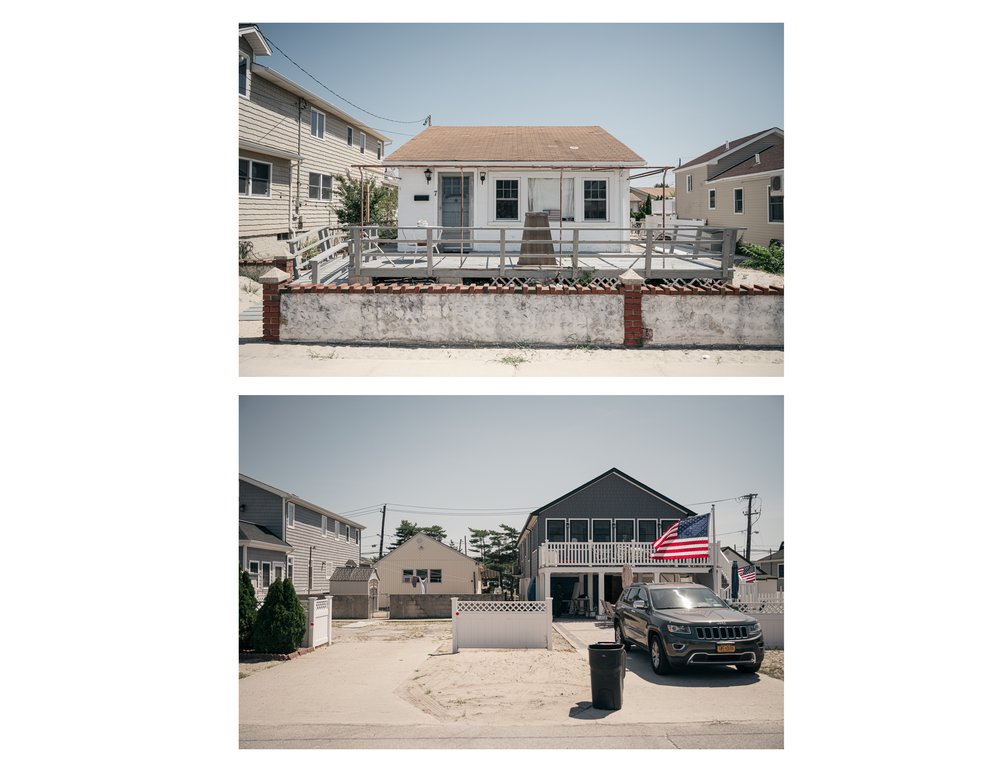

Today, there is very little evidence that fires and floods consumed the community a decade ago, but that night still left its mark in other ways. Before the storm, homes had outside sitting areas on street level. For Ingram, a lifetime resident, it meant that walking past his neighbor’s home could always suddenly lead to sharing a quick beer together.

The foundations for rebuilt homes are now required to allow for future water surge to go underneath them. Otherwise, the structure must be totally open underneath its first floor with just concrete pillars enclosed with lattice. According to Lighthall, this doubled how much homes were previously raised off the ground.

Since the homes have been lifted several feet, those ground-level patios have become second-story decks that separate neighbors with a set of stairs and a height difference, creating a barrier to those spontaneous social interactions.

“Everybody was on their front porch, and everybody knew everybody,” Neimeth said. “But with the new rules and the houses have to be built up on stilts and with air conditioning — it's not the same, of course, as the old days. No. No, it's not the same.”

History lessons from Sandy

The storm taught Balukas a lesson in the urgency of preserving the local history stored within ordinary cupboards and underneath beds. Currently, the pile of incoming Breezy Point relics still wrapped in lumpy manila packages towers over everything else on the front desk.

Each package is opened and catalogued. If it’s a photo or a paper item such as a periodical or a map, it's immediately scanned and returned. A new committee was recently formed to determine what is historically significant enough to Breezy Point to be included in the organization’s collection, which includes thousands of digital archives as well as physical objects.

“Seeing the stuff from the past really brings back a lot of fond memories,” Balukas said.

While the rules about submitting an item for consideration in its archives are not stringent or even set in stone, there is one unwavering requirement: It must be directly connected to Breezy Point. Otherwise, the society keeps an open mind, and digitizes as much as it can. The scanned home movies and family photos are, by far, the most popular items among its members. These offer the most immediate connections to personal pasts.

“Their history was taken away from them. Their memories were taken away from them,” said Balukas, a summer resident who has shared his own Breezy Point photos and videos that were spared from damage because they were stored at his primary residence in Brooklyn. “There was a strong desire to try to get some of that back by going to other people who didn't lose everything.”

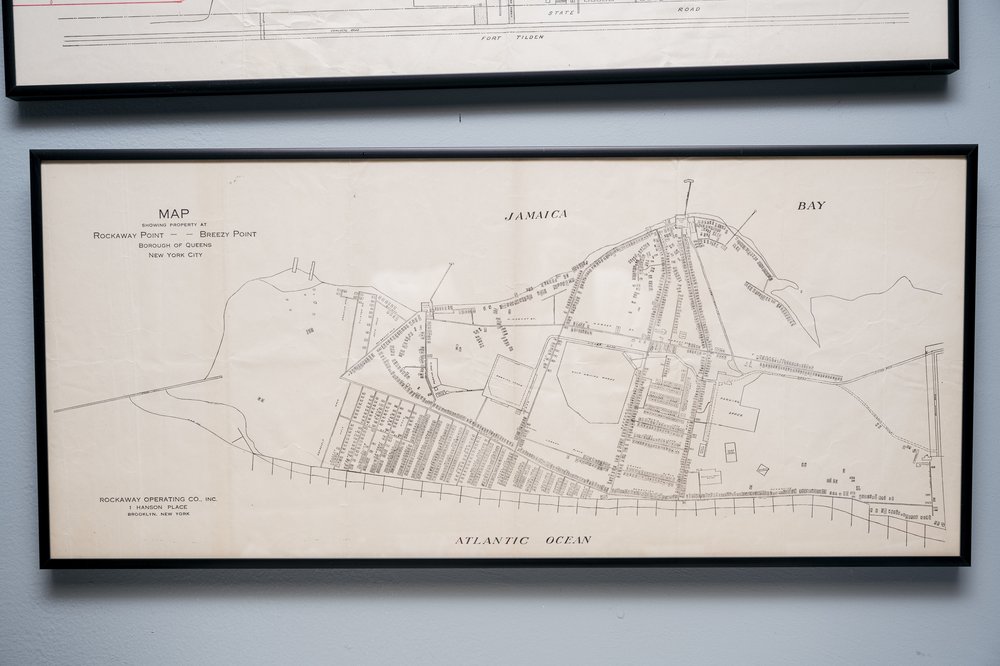

Breezy Point started out as a working-class summer tent community in the 1910s and 1920s.

Using an archive of old newspapers and donated pictures, the historical society traced the neighborhood’s beginnings to 10 old platform sites that families rented and draped a large piece of canvas over for shelter.

There was no indoor plumbing or electricity, but the beach was just steps away. Water was limited, and to get ice to keep food from spoiling in the refrigerator, residents had to wait for the iceman to come around. A set of large iron tongs used to serve these frozen blocks sits heavy and rusted on top of a metal filing cabinet in the society’s office.

“It was really a paradise for children,” said Balukas, 65, who spent the summers of his youth in Breezy Point and lived in Brooklyn for most of the year. He spent his two-month breaks from school fishing and swimming in the ocean and bay.

What makes a piece historically significant is something the historical society is still trying to figure out as it is inundated with old trophies and household ornaments. The current pieces fit in anywhere they can. A pinewood zither, or lap harp, in a clear plastic bag leans against the wall behind a door. It was once played at a local theater during the silent films that showed in the 1920s and 30s. It was rescued from Sandy, too, and looks as good as new.

The 18-member board of trustees is also on the lookout for anything from the late 1800s or prior. The historical society is trying to discover what came before the beach tents, and how far back it can travel in local history. The organization believes hotels and beach clubs may have once dotted the peninsula’s coastline.

The endeavor is financed completely by its members with their $25 yearly dues and ticket sales from the annual Hall of Fame dinner, where residents are honored for their work in the community for $60 a plate.

The nonprofit is also supported by volunteer staff and donations. As the collection grows, objects are also kept off site in co-op storage and members’ homes. Their own office space is about to shrink because another tenant is moving into the medical center. Finding adequate room for an expanding exhibit will soon pose an even greater challenge. The members are more focused on collecting, cataloging, and coordinating lecture series that draw a packed house to learn about photographs and videos in the collection.

Preserving the past from future floods

The top priorities of its newly formed cataloging committee is to get through the backlog of items donated for preservation and then find a way to make all of it accessible to the community before the next storm hits.

“They are already picking up the pieces for us before the event occurs,” Ingram said.

Before bridges linked the Rockaway Peninsula to Brooklyn, everything came over by ferry. It was common practice to pick up driftwood, or anything floating in the water that could be repurposed for building seaside shacks. These more permanent structures replaced the summer tents that had to be rebuilt year after year for just two months' stay.

“Breezy Point is very working class,” Baluka said. “It’s known for having a lot of police officers, a lot of firemen, and a lot of city employees, predominantly Irish, but that’s changing.”

Eventually the shacks became the bungalows that were common in the area before Hurricane Sandy. In 1961, the Breezy Point Cooperative was established from three neighborhoods: Rockaway Point, Roxbury, and Breezy Point itself. It owns the entire community, including the beach and more than 2,800 homes. It even hires its own lifeguards.

The only public property is Rockaway Point Boulevard. Outsiders who step off it are met with electronic gates and security at every entrance barring the way.

It’s really hard to buy a house on the west side of the Rockaway Peninsula. The cooperative requires 50% down in cash and three reference letters from existing shareholders. Most homes are passed on from one generation to the next, according to Lighthall, who inherited his home from his parents, who in turn inherited it from theirs.

These houses are like neighborhood time capsules with attics, closets, and drawers stuffed with generations of old home movies and other tangible clues to Breezy Point’s past and its inhabitants.

But as it reconstructs the history with rescued fragments, the Breezy Point Historical Society doesn’t have much time.

Over the next 30 years, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts tide and storm surges will increase further inland, which means floods like Hurricane Sandy will happen 10 times as often.