Brooklyn mom continues fight for safer streets a decade into NYC’s Vision Zero program

Jan. 16, 2024, 5:01 a.m.

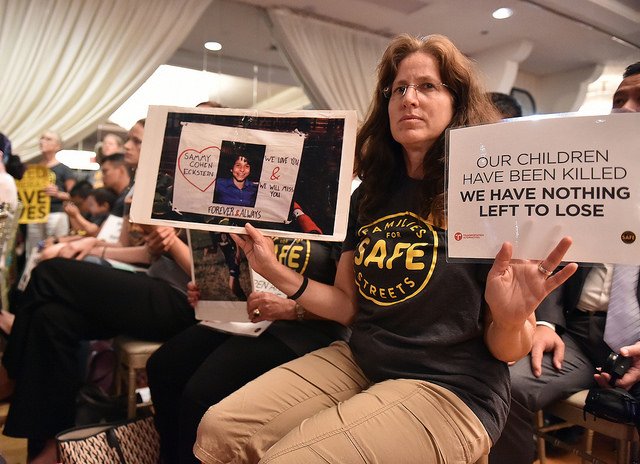

Park Slope, Brooklyn resident Amy Cohen co-founded Families for Safe Streets just months after her 12-year-old son was struck and killed by a van in 2013. She hasn’t looked back on the fight for safer streets since.

A Brooklyn mom has been an advocate for Vision Zero and safer streets since her son's death in 2013. Now, as the program that aims to eliminate all traffic deaths and serious injuries turns 10, she is still working to improve road safety, including getting a long-stalled bill named after her son approved in Albany.

“Sammy was an incredible kid. I mean, really an all around wonderful person,” Amy Cohen said. “He was kind, he was smart, he had many talents. He was a musician and an athlete.”

Sammy died at 12 years old on Oct. 8, 2013, after being struck by the driver of a van outside of their apartment building. It happened as Sammy went to retrieve a soccer ball that rolled into the street. The cars in one lane of the one-way roadway stopped for him, but Cohen said the driver of the van in the other lane was going “way too fast” to avoid hitting her son. The driver had his license temporarily suspended, but was never criminally charged.

“It is a cliche, but it is so true, Cohen said. “There's just always an empty seat at the table.”

She channeled her anguish into activism in hopes of shielding other parents from the heartbreak of losing a child at the hands of a reckless or speeding driver.

Cohen went on to connect with other families who suffered similar losses and in 2014 they formed Families for Safe Streets. Along with Transportation Alternatives, the group has focused on policy changes that are central to Vision Zero, including reducing speed limits, getting speed cameras and better road design. In addition to New York City, the group has grown to have chapters across the country.

Cohen is now inching toward a new milestone, passage of a lingering bill in Albany named for her son. Sammy’s Law, first introduced in 2020, would allow New York City to set its own speed limits. Right now, the city can't adjust speed limits without the state's approval.

Cohen took part in a four-and-half day hunger strike in June to pressure Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie to bring the bill to the floor for a vote, but those efforts fell flat. Gov. Hochul has now committed to reintroducing the bill as part of the FY 2025 executive budget.

As part of WNYC and Gothamist’s coverage of Vision Zero’s 10th anniversary, we spoke with Cohen about her son, activism and ongoing efforts to improve road safety.

The conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and content.

How did your work in activism take shape?

I just had so much pain it had to go somewhere. And my husband had said to me, if only this had been London, Sammy might still be alive. We had gone there on vacation a few weeks before. We had seen the changes that they put in place to make roads safer. They designed their roads for safety, they lowered the speed limits, they put priority on people's lives over getting to your destination two minutes faster. It's outrageous that it's taken us as long as it has to do the same here.

When did you first make your voice heard on the issue?

A few weeks after Sammy died, we heard about a city council hearing on lowering the speed limit in New York City. And so I contacted our city council member, Brad Lander, and I asked if we could testify. I had never done anything like it before. We all spoke. Me, my husband, my daughter. I think people who'd been trying to make change for a long time went, “Wow, if you give a face to this crisis, it really does make a difference.” So right away I started speaking out. In partnership with Transportation Alternatives, I connected with other family members who'd either had a loss years ago or more recently. We held our first meeting only a few months after Sammy died. And early in 2014, we announced ourselves as Families for Safe Streets and said our first fight was going to be to lower New York City's speed limit.

What was that battle like?

We had no idea what we were up against. As we went on our first trip to Albany, legislators were telling us to change a state law could take ten years, you better brace yourself for that. And I was thinking, ten years? I don't think anyone could live with this pain for ten years. And we didn't give up. We went on many trips to Albany. We spoke out in the press, most of us doing this for the very first time, and we did it in one legislative session.

Was that a celebratory moment?

You know, truthfully, I could never have imagined celebrating in any way at that point. But we were fighting collectively with people who had lost loved ones 10 years before. I remember at one of our meetings, two of our members were laughing in the corner, you know, and catching up. And I thought, I will never laugh again. But we did. We, you know, we did celebrate after that win.

What did you take away from that?

You really can make change when you have the moral authority and you say, you know, this is not okay. You can't put a few people who are opposed ahead of all the lives that are being taken because of your bad political choices. It's really a matter of political will. We know what the tools are to solve this crisis, and we just need our leaders to put them in place.

What are those tools?

Truthfully, we are never going to solve this crisis by changing driver behavior one driver at a time. Right? We are going to solve this crisis by fixing our roads, putting in place safe speed limits, installing technology and redesigning our vehicles so that our people can be safe no matter how they get around. Whether they're walking, biking, driving, or a passenger, we want everybody to be safe. That's what Vision Zero is about. It's achieving zero traffic deaths for anyone regardless of how they get around. And we know it can be done. There are cities in Europe that have gone years without anyone being killed. We know what the solutions are, and other people have proven it is possible.

What have been your proudest moments? When the tears turned to smiles?

Certainly there's the legislative victories we've, you know, successfully fought early on for that first step in lowering New York City speed limit, redesigning Queens Boulevard from the boulevard of death to the boulevard of life, helping to fight for the streets master plan, which will redesign our most dangerous arterials, but there's the times when you're there for another family. When you connect them up with somebody with a similar loss. Families for Safe Streets has a two part mission – we confront the preventable epidemic of traffic violence through advocacy and support, and we believe no one should have to go through this alone. We have a team of social workers, now English and Spanish speakers.

What are your current priorities?

Right now I am fighting for a bill, actually named after my son, that would allow New York City to have full control over its speed limit. I grew up in a rural area north of Albany, and it's a whole different world. Why are the legislators from other parts of New York State dictating what the speed limit should be on a residential street in New York City? I mean, it's really insane, and it shouldn't take our fourth legislative session to fight for that change. When we know it will save lives, it's a simple measure. It doesn't cost anything. Why is change taking so long?

How do you work to make your case with lawmakers?

We bring photos, we tell stories, and we help them realize it's a real person who lost their life. And then we're very data driven, you know, we always have facts and statistics about why a particular solution is critical, where it's been used previously, and how it's worked. The problem has not gone away. And so we're not going away. And you know, I have no plans to give up, but if I ever did, I feel like we have spawned a movement. And it will live on, even if something happened to me.

Friends gather in Brooklyn to mourn cyclist killed by truck driver Advocates push Hochul to expand NYC's Vision Zero program statewide