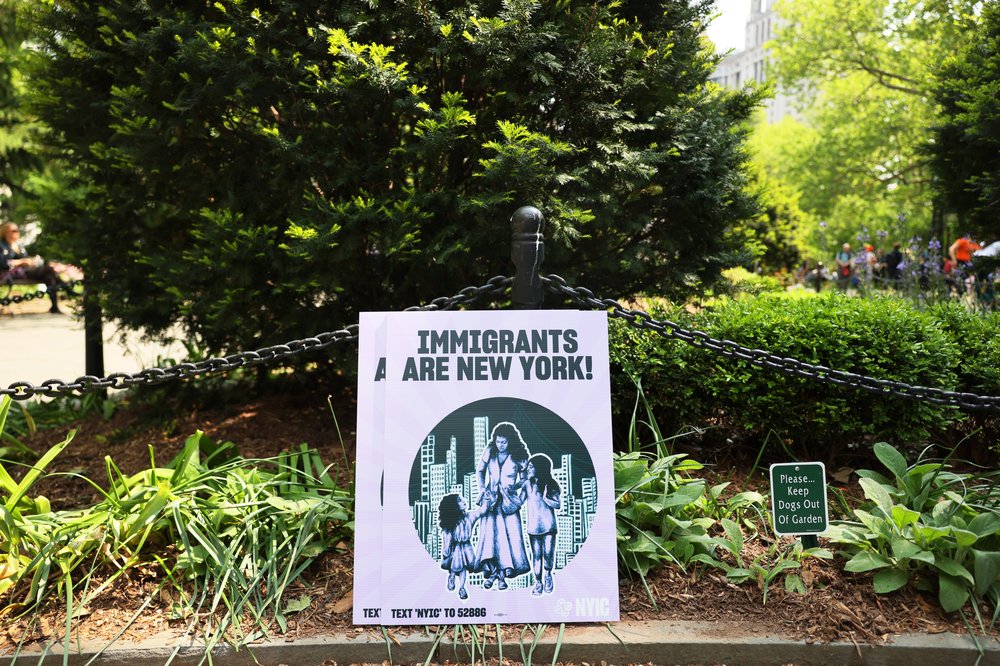

As NYC preps for more migrants, new arrivals share hopes, fears and thoughts on the Big Apple

May 17, 2023, 6:02 a.m.

The end of a pandemic-era border policy last week is spurring renewed urgency for city and state officials as they prepare for more newcomers.

For the past year, tens of thousands of migrants fleeing violence and economic and political instability in their home countries have arrived in New York City after treacherous journeys to reach the U.S. But with the expiration of a pandemic-era policy last week that allowed migrants and asylum-seekers to be turned away at the U.S-Mexico border, the city is bracing itself for another uptick in new New Yorkers that officials worry will rupture already strained social safety net programs.

With the end of the Title 42 border rule last week, officials expect an increase in the number of migrants arriving in the city daily on top of the roughly 60,000 newcomers arriving in the last year — about half of whom are living in city shelters and emergency housing.

Mayor Eric Adams and Gov. Kathy Hochul are pleading with the White House for additional resources to house and manage the newcomers, all while trying to identify locations throughout the five boroughs and beyond that could be repurposed into emergency shelters.

New York's newest residents are facing long waits in immigration court and when applying for work permits. And city lawmakers and nonprofit providers have described chaos and confusion, with several nonprofits and volunteers having to help migrants navigate the intricacies of arrival on their own.

As local and national conversations among elected officials along the political spectrum are underway over how to respond to the anticipated flow of new arrivals, Gothamist spent the last two weeks talking to some of the newest New Yorkers, who are in various stages of rebuilding their lives in the U.S.

Here are their stories:

Ana Arrieta 29, Gino Cifuentes 39, and their 4-year-old son

- Native Country: Colombia

- Time in New York City when interviewed: Two days.

- First English word/phrase learned: “I do not speak in English.”

Two days after arriving in New York City via a bus from Texas in early May, Ana Arrieta, 29, and her partner Gino Cifuentes, 39, stood outside “The Little Shop of Kindness” in Midtown with their 4-year-old son. They were there to pick up clothes — an urgent necessity for those recently arriving from the southern border.

The free “store” run by advocacy group Team TLC NYC out of the Seventh-Day Adventist Center was so overwhelmed that the family was turned away, Arrieta said. But still they remained in good spirits.

“We feel safe, we feel calm, we feel well taken care of,” Arrieta said in Spanish, walking through Times Square back to the Watson Hotel in Hell’s Kitchen, one of the sites the city is using to house families arriving from other countries.

The couple hopes to find work of any kind, and legally, they say. They want to be able to provide for themselves and set down roots in the city.

Cifuentes said that everything here is different from their home in Colombia, from the culture, to the architecture, and the food — but he likes it.

“I understand the signs that say, ‘I love New York,’” Cifuentes said. “It’s a dream to be here.”

The family was able to fly from Colombia to Guatemala, but traveled the rest of the way mostly by foot. Arrieta said there wasn’t a moment where they felt safe in Mexico, describing their 15-day journey through the country as traumatic. She added that the relief of feeling safe after a treacherous journey was overwhelming.

“I don’t know how to explain it, it’s a feeling of peace. Like thank God, because after the storm, it’s as if the calm is finally arriving,” she said.

There is one thing Cifuentes said he could do without.

“You know what I don’t like, people smoke marijuana everywhere! It’s true, that smell is everywhere, I was saying it was giving me a headache,” he said.

Ricardo Mafla, 35

- Native Country: Colombia

- Time in New York City when interviewed: 20 days.

- First English word/phrase learned: “Welcome.”

Just a few weeks after arriving in New York City, Ricardo Mafla, 35, walked past a line on the street and asked what it was for.

“They told me it was to receive food … so I decided to join the line,” he said. There, someone handed him a flier for the New York Immigration Coalition’s resource fair, “Key to the City” — where community-based organizations connect people to health care, education and public benefits enrollment.

As city agencies struggle to keep up with demand, community-based organizations have been a lifeline for migrants arriving in New York City. But while many do outreach in communities, asylum-seekers often find out about resources by chance or through word of mouth.

Mafla said he was able to set up a consultation appointment on his asylum case with Legal Services NYC, which provides free clinics at the resource fairs. He said he felt his life was at risk in his home country due to issues with an armed group in Colombia.

“A lawyer heard my case and if things can be done in the process to ask for asylum, God willing,” Mafla said. ”It's a good experience because you arrive in a country you don't know and they give you help, they advise you to go to another place to find help to make it a little easier for us.”

For now, he’s staying with an acquaintance in Jackson Heights and hopes to find a job soon.

Patricia Guachamboza, 44

- Native country: Ecuador

- Time in New York City when interviewed: One month.

- First English word or phrase learned: “Good morning.”

Patricia Guachamboza, a single mom, arrived in New York City last month after leaving Ecuador with her 17-year-old son and 20-year-old daughter. She said the economic situation back home, combined with a surge in crime and death threats at her son’s school, forced her and her family to leave.

It’s been around a month since she first arrived in New York City and although she was able to secure a room at the Watson Hotel in Hell’s Kitchen, she said finding work and navigating a new city is a much bigger challenge.

“The truth is it is so hard, so hard to find a job. One of the biggest problems is that we don't know how to speak English,” she said in Spanish, standing outside the hotel.

“There are people who are lucky. They say it’s better to be recommended for a job, but really, when you arrive in another country, you don't know anyone,” Guachamboza said.

So far, Guachamboza said she has relied on the goodwill of strangers when navigating the subway system in the city. She’s hoping that soon, someone will point her in the direction of a job.

“I don't want to be a burden for the government, for it to support us or to give us everything, but we want to be self-sufficient ourselves to be able to cook, have our own, if we have to pay taxes, pay for everything, to be able to be in peace and carry on,” Guachamboza said, adding that she looks forward to one day making rice in a home of her own.

Cesar Augusto Abril, 34

- Native country: Venezuela

- Time in New York City when interviewed: Five months.

- First English word or phrase learned: “Hello, hi, you’re welcome, thank you so much.”

Cesar Augusto Abril, 34, arrived in New York City with his partner, Estefani Pozo, 31 and their three kids — ages 5, 8 and 12 — in January.

“Happiness,” Abril said, describing his feelings upon arrival. “Happiness and well, a little bit of everything — the change was felt.”

The family left their home in Venezuela, trekked through the jungle of the Darien Gap and spent a few months in Mexico before entering the U.S. at the southern border through the CBPOne app, an authorized portal for seeking asylum at the border that is reportedly riddled with tech issues.

They were able to get their kids in school on their second week in the city. Applying for asylum is taking longer, but Abril already applied for work authorization and hopes to get it in the next three months.

Securing work permits for migrants is among the top issues for New York’s leaders, from the mayor to the governor to members of the congressional delegation.

“[The plan is] as soon as the papers come in: Get a job and try to get out of this hotel as soon as possible, and to relocate to an apartment and be stable,” Abril said.

In the meantime, he’s been able to make some money delivering food — usually for eight to 12 hours a day — using a bike he rents from a friend. It’s a line of work many of the men staying at the Watson Hotel — which is being used to house families — have gotten into, as evidenced by the number of bikes locked up out front.

María Gabriela Chica, 30

- Native Country: Ecuador

- Time in New York City when interviewed: Six months

- First English word or phrase learned: “You’re welcome.”

Maria Gabriela Chica, 30, said her family left Ecuador due to the crime, violence and scarcity of resources the country is experiencing. She said they plan on applying for asylum, but they’re worried they don’t have the necessary evidence to prove their case.

“We arrived here with nothing, empty-handed — we have no documents, we have nothing. So we have to seek advice from lawyers to see what we can do and what will happen to us if we do not qualify for asylum,” Chica said.

Chica, her husband and two children are also staying at the Watson Hotel in Hell’s Kitchen. Five-and-a-half months after arriving in the city, her husband was finally able to find a job in construction.

“I am aware that we have to leave here soon, because just as I have been here for five months, there are people who are just coming. They are going through the same situation without a job. And they need it,” Chica said. “I need it too, but as I’m telling you now, since my husband already got a job, it's time to pick up and see.”

Omar Isea, 40

- Native Country: Venezuela

- Time in New York City when interviewed: Six months, but two years in the U.S.

- First English word or phrase learned: “I want to take a shower.”

Omar Isea arrived at the Texas border in May 2021, before finally making it to New York City in November.

Since then, he said he’s cycled through a number of living situations as the city shuffled him around from shelter-to-shelter. He still remembers the first phrase he learned in English during that time.

“I want to take a shower,” he said, in English standing outside the hotel where he is currently housed in Midtown. “I wanted to take a bath so much that a word came out in English,” he added, in Spanish.

In Venezuela, Isea worked as a contractor for oil companies. Two years after first arriving in the country, he’s secured a social security number and work authorization, the highly coveted documents other migrants and asylum-seekers are looking to obtain.

His first job in the city was as a dishwasher.

“A very fast job. Here, things are fast, it’s another rhythm,” Isea said. “You make friends in the kitchen, people from another culture, perhaps the same language, but other cultures, too, and you adapt, little by little.”

Now, he’s enrolled in a home health aide course at a professional development school in Manhattan.

“My short-term goals are to finish the course, to start working, have a little more money saved and have a little more independence,” Isea said. “To see my daughter grow up and lead a normal life, just as every normal person wants to do and without harming anyone. That’s the only thing we want, all the Venezuelans — we want to live.”

This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Ricardo Mafla's name.

A year after the first asylum seeker buses left Texas, is NYC ready for more? Mayor Adams suspends NYC review process for building shelters as more migrants arrive