An NYC student’s yearslong struggle to get proper instruction for dyslexia

Sept. 25, 2023, 5:01 a.m.

Gothamist followed Matthew Green and his grandmother as they learned he had dyslexia, a revelation that sent them into a complex world of neuropsychiatrists, lawyers and private schools.

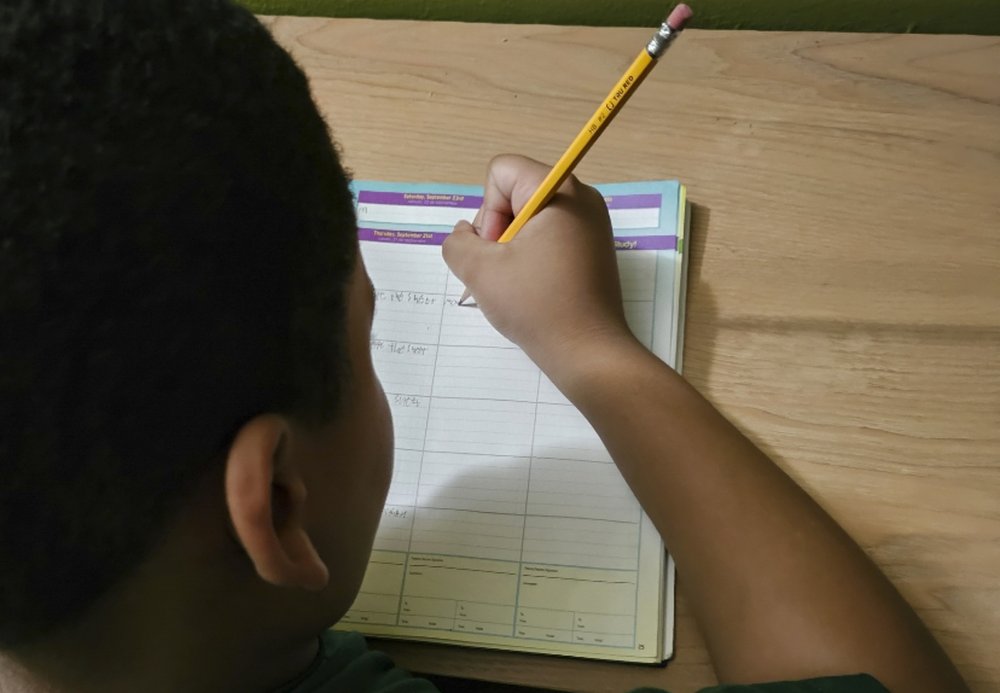

Matthew Green, 9,writes in his planner. For a long time he thought he was a “bad” kid. Like so many young students with an undiagnosed learning disability, he blamed himself for his boredom in class and deep aversion to reading and math, which often manifested in disruptive outbursts.

When Matthew Green tries to read, his frustration flares. Then, as he puts it, he shuts down.

“I get an attitude sometimes, I start to cry sometimes,” he said. “My brain is like ‘I can't handle it.’”

For a long time, Matthew, 9, thought he was a “bad” kid. Like so many young students with an undiagnosed learning disability, he blamed himself for his boredom in class and deep aversion to reading and math, which often manifested in disruptive outbursts.

His grandmother, Trenace Green, with whom Matthew lives in Harlem, grew increasingly exasperated with his public school as he fell further and further behind.

“It's clear that he's behind and he can't function here, and to have to fight for even the most basic services, it's so heartbreaking,” said Green, 51.

- heading

- Navigating a "Byzantine" process

- image

- image

- None

- caption

- body

- Hear this story on NYC Now, our daily podcast.

- An accompanying article, So You Think Your Child Might Have Dyslexia, provides a resource for families about to enter New York City's system for kids with the learning disability.

- Gothamist plans to follow the rollout of Mayor Eric Adams' efforts to improve literacy instruction in public schools and check back in with Matthew Green as he attends a private school.

- Have experience in the public school's system for learning disabilities that you'd like to share? Contact education reporter Jessica Gould at jgould@wnyc.org.

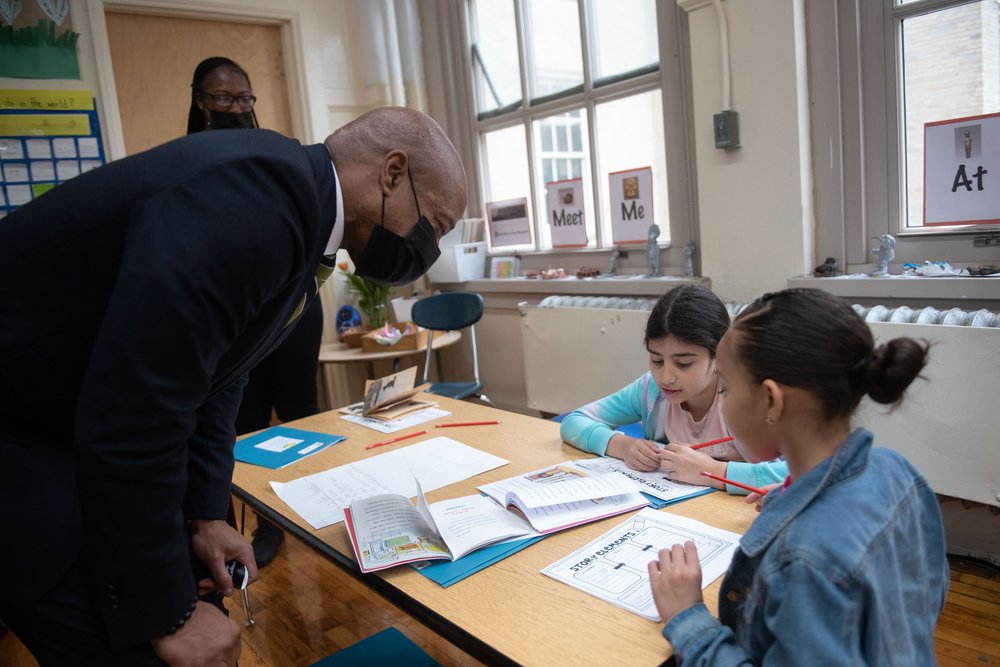

Mayor Eric Adams has made teaching public school children to read – and particularly children with dyslexia – his signature educational initiative.

But for decades, city schools have been using disproven reading methods. Teachers have been advised not to tell families when they suspect students may be dyslexic. And families that do realize their children need help are often forced to hire pricey attorneys and sue the school district in order to send their children to specialized schools.

Experts estimate that 5% to 20% of students may have some degree of the language-based learning disability. But the nation’s largest school system has historically been unable to identify students with dyslexia or offer the support they need.

For the last seven months, Gothamist has followed the Green family’s efforts to compel the city to comply with federal laws that require all students receive a "free, appropriate education." It's part of a yearlong project exploring the rollout of promised reforms aimed at helping kids like Matthew.

“You have to hire an attorney just to get your children educated. How is this possible?” Green said.

An Adams priority

Adams knows firsthand what it’s like to be a student with dyslexia in New York City schools. He’s recalled not knowing he had the disability, and enduring taunts from classmates in South Jamaica, Queens who taped a sign reading “dumb” to his chair. Adams has likened the treatment of students with the disability to a “Shakespearean tragedy.”

“You stand up and you have to read, and you stumble over the words and you cringe and you start to think differently about yourself,” Adams said in an April speech at the World Dyslexia Assembly at Lincoln Center.

Even when teachers suspect their students may be dyslexic, it can be hard for them to get help. Some teachers told Gothamist that they were regularly instructed by administrators not to use the word “dyslexia” when speaking with the families of students they suspected have the disability. And for decades, many teachers taught reading using disproven strategies that are particularly difficult for students with dyslexia. Education Chancellor David Banks began phasing out those techniques last year.

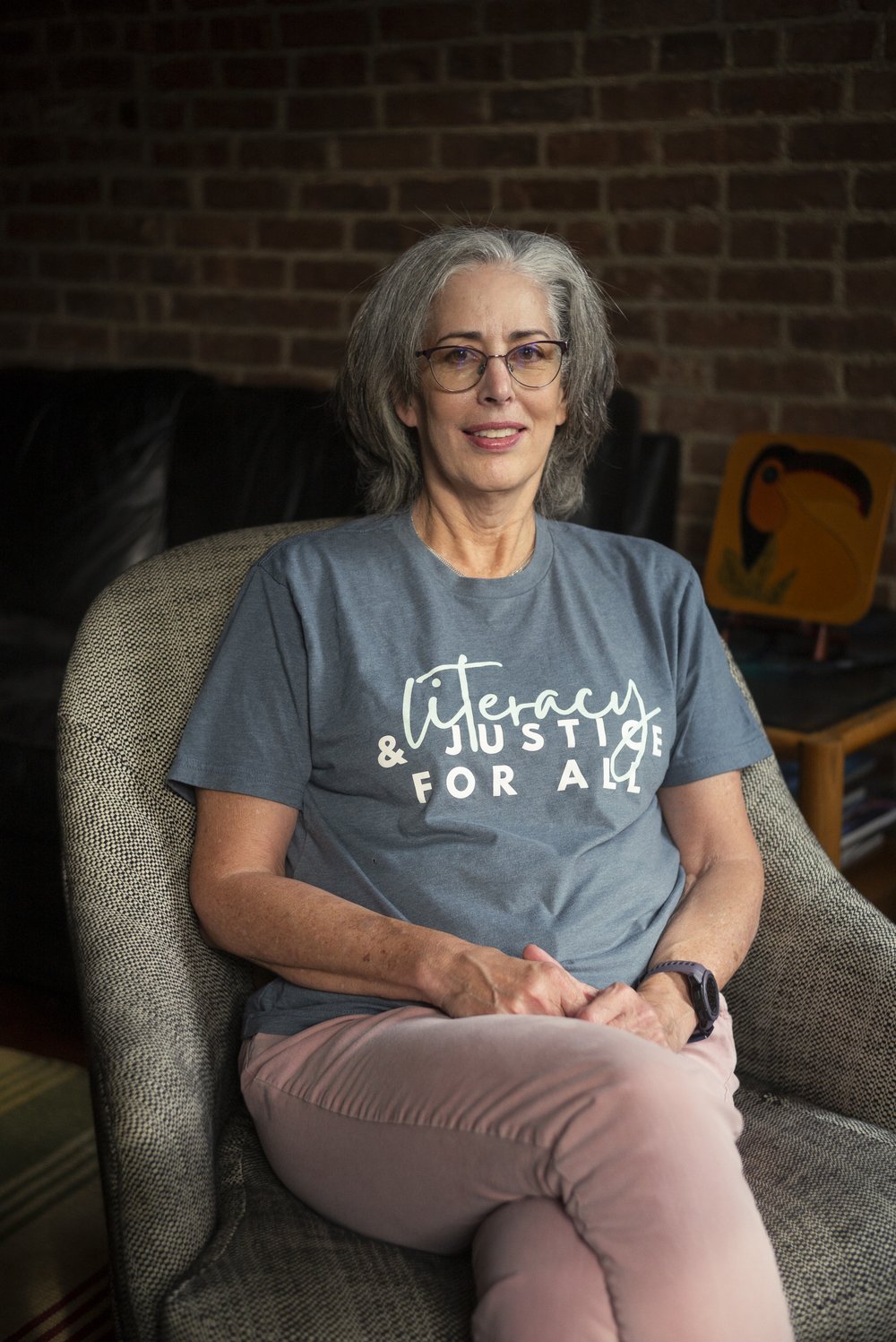

“If you look over my career, I personally am responsible for probably 40 to 50 children not learning how to read. That's a hard thing to admit. I personally feel horrible,” said Teresa Ranieri, a literacy specialist in the Bronx who now helps educators learn better practices.

Public schools offer an array of services for special education students. But for many dyslexic students, those services are inadequate. Parents who look beyond the public schools for help discover a deeply unequal system where wealth and personal connections often determine whether a kid with dyslexia receives an adequate education.

In dozens of interviews with Gothamist, multiple families discussed how they have tried to support their children with dyslexia. Many pay for neuropsychological evaluations, which can cost up to $10,000. Some seek private tutoring, which can cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars a month.

Others opt for specialized private schools, with tuition topping $70,000 a year. They hire attorneys, paying thousands of dollars for retainers. While most families sue the city for reimbursement for tutoring or tuition, they often have to front the costs before getting paid back – sometimes waiting as long as two years. As a result, affluent families are far more likely to take that route.

Most of the legal settlements for private school tuition reimbursement are made with families who live in the wealthiest neighborhoods, according to an analysis last year by news website The City.

The cost of sending students outside the public schools is also a drain on city coffers. In fiscal year 2022, New York City paid nearly $1 billion to cover services and tuition at private schools for students with disabilities, including dyslexia.

Deputy Chancellor Carolyne Quintana, who oversees the school system’s efforts to improve instruction for students with dyslexia, said it’s stories like Matthew’s that drive the city’s ongoing overhaul.

“We understand that there's in general a crisis in terms of how we've been teaching reading, and this crisis is especially significant for any of our young people who either have been diagnosed with dyslexia or who may be at risk,” she said.

“We don't want parents to have to feel like they need to go outside of their local community to get the support that their child needs…That's not the experience that a family should have when they have public schools nearby.”

A lack of support

Matthew’s struggles manifested in his behavior. He disrupted class, got into fights and even threw chairs. “I would get calls at least once a week,” Green said. “It was really bad.”

At one point, Green recalled that Matthew’s teachers gave him a teddy bear in the hopes it would calm him. It didn’t.

Last year, in third grade at P.S. 133 in Harlem, Matthew was barely reading at a first grade level.

Green tried to help Matthew practice at home, coaxing him through reading assignments every night. She requested an evaluation for special education services, and lobbied for more intensive literacy support. Matthew’s individualized education program – a written roadmap for students with disabilities – shows the school offered placement in a smaller class for kids with a wide range of disabilities and some group psychological counseling on the side. But his teachers, like most public school teachers throughout the city, were not trained in how to teach students with dyslexia, and the school did not offer additional literacy support. Green said it seemed like the school did not have a plan to help him.

“He wasn't getting the support that he needed,” she said. “We do not have a year to take this wait-and-see approach.”

A mounting sense of urgency

Time was of the essence.

Pediatric neuropsychologist David Salsberg said it's key to identify and support students with dyslexia as early as possible. “When it's past third grade, the literature research doesn't support that you're gonna really move that much of the needle on the mechanics” of learning to read, he said.

Green, Matthew’s grandmother, was his relentless advocate. She works nights at an information technology job and until this year, she devoted her days to getting Matthew help with learning to read. “Every waking moment I was thinking about it,” she said.

She feverishly searched online and contacted other parents. She enrolled in a class on how to advocate for a child in special education. It was a full-time job on top of the one she already had. “It’s overwhelming, exhausting and just with a system that seems designed to fail,” she said.

Green gradually immersed herself in the cottage industry that has developed to serve students with dyslexia. Advocates, experts, attorneys and private schools are available to assist, but figuring the system out takes an enormous amount of time and the price can be high.

“It's just so much to learn and navigate through,” said Green.

Through a local listserv, she connected with Debbie Meyer, chief operating officer of the Dyslexia Alliance for Black Children. Meyer guided Green through what she describes as a byzantine system that has evolved to support students.

“There are multiple pathways” to getting students the help they need, Meyer said. “But when you have a large checkbook those pathways get much shorter.”

Families that are able to hire private attorneys, pay out of pocket for neuropsychological assessments, and front tuition for private school before getting reimbursed can get their children the help they need much more quickly. Some families who don’t speak English or lack the flexibility to spend hours navigating the bureaucracy never learn the additional resources that are available.

The stakes for students with dyslexia

Research has found untreated dyslexia often leads to behavioral issues, anxiety, aggression and social withdrawal. Adults who have never learned to read adequately are more likely to be underemployed, incarcerated or have health problems. A seminal study of a Texas prison found that 48% had literacy challenges indicating dyslexia.

“I was on that pathway, to join that rank,” Adams said in April.

Banks, the schools chancellor, has said the city has “done our kids a disservice, and it doesn’t have to be that way.”

The city is now rolling out a series of reforms.

Last year, the education department expanded literacy screeners to identify students at risk of reading problems. Those students then get additional reading help in small groups or one-on-one, with follow-up assessments to check their progress.

The city also launched “structured literacy” pilot programs to give public school teachers extra training in the techniques considered the gold-standard in teaching students with dyslexia.

Schools are beginning this fall to overhaul literacy instruction systemwide with new curricula officials say will help all students, including many with dyslexia, learn to read.

A breakthrough

Green and Matthew were lucky. He qualified for a study that provided a free neuropsychological evaluation from the Child Mind Institute.

Next, Green needed to find a lawyer to represent Matthew in a suit against the education department seeking reimbursement for private school tuition. She called lawyers for weeks to no avail. She finally found Andrew Gerst, a public interest attorney with Mobilization for Justice. He said he would help, at no cost to her. Legal fees for those types of suits can cost several thousand dollars.

She also found Matthew a seat at the private Sterling School in Brooklyn, one of the rare schools that offers many slots to families who can’t pay up front.

But if she doesn’t win her case, she remains on the hook for the annual $75,000 tuition she doesn’t have.

“So that hangs heavy over my head. It's still a gamble,” Green said.

During a tour of the school over the summer, Green felt a welcome sense of hope. While initially hesitant to switch schools, Matthew became enamored with the Sterling School’s STEM lab, small classes and stacks of books. He was eager to learn to code.

“I love this school,” he said.

Gothamist will be checking in with Matthew during the school year. Do you have experience in New York City’s system for public school students with dyslexia? Contact reporter Jessica Gould at jgould@wnyc.org.

Mayor Adams proposes $7.4 million plan for public schools to address dyslexia With test scores low, NYC schools turn to new approach for reading instruction