Zines are back: Brooklyn Museum exhibit looks at decades of artistry

Nov. 26, 2023, 8:01 a.m.

Zines have recently been making a comeback in NYC.

Zines have been making a comeback in the past few years.

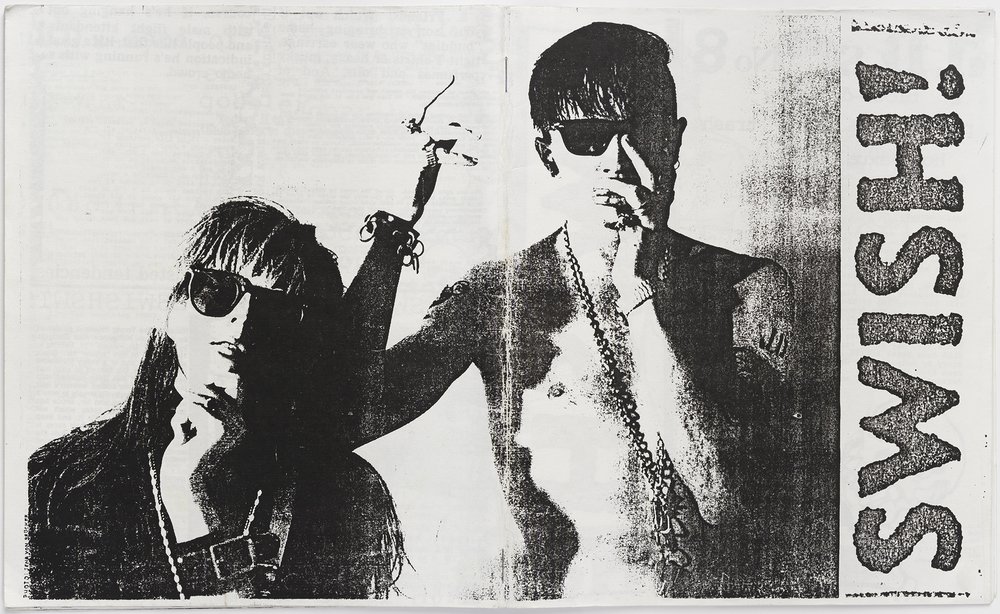

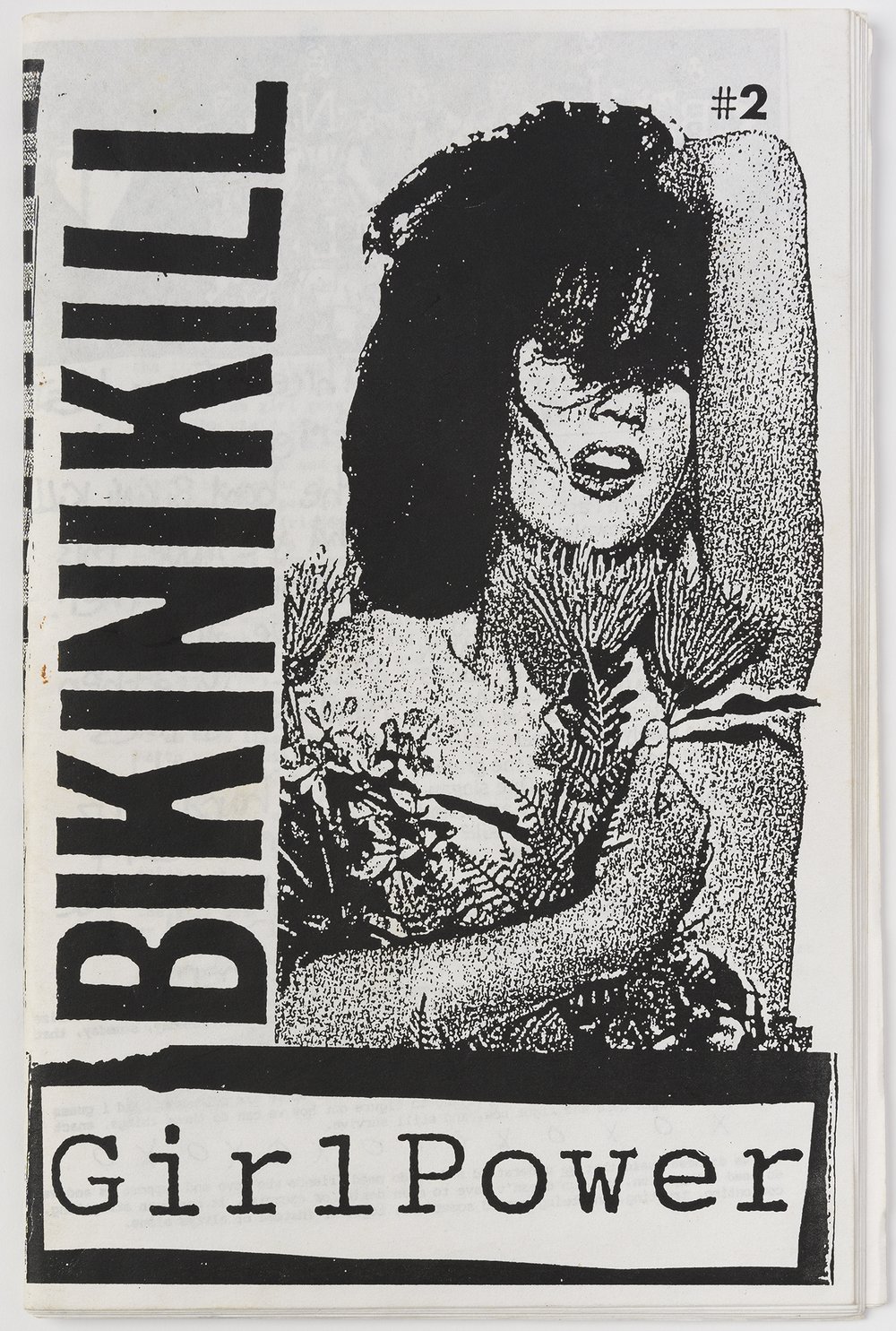

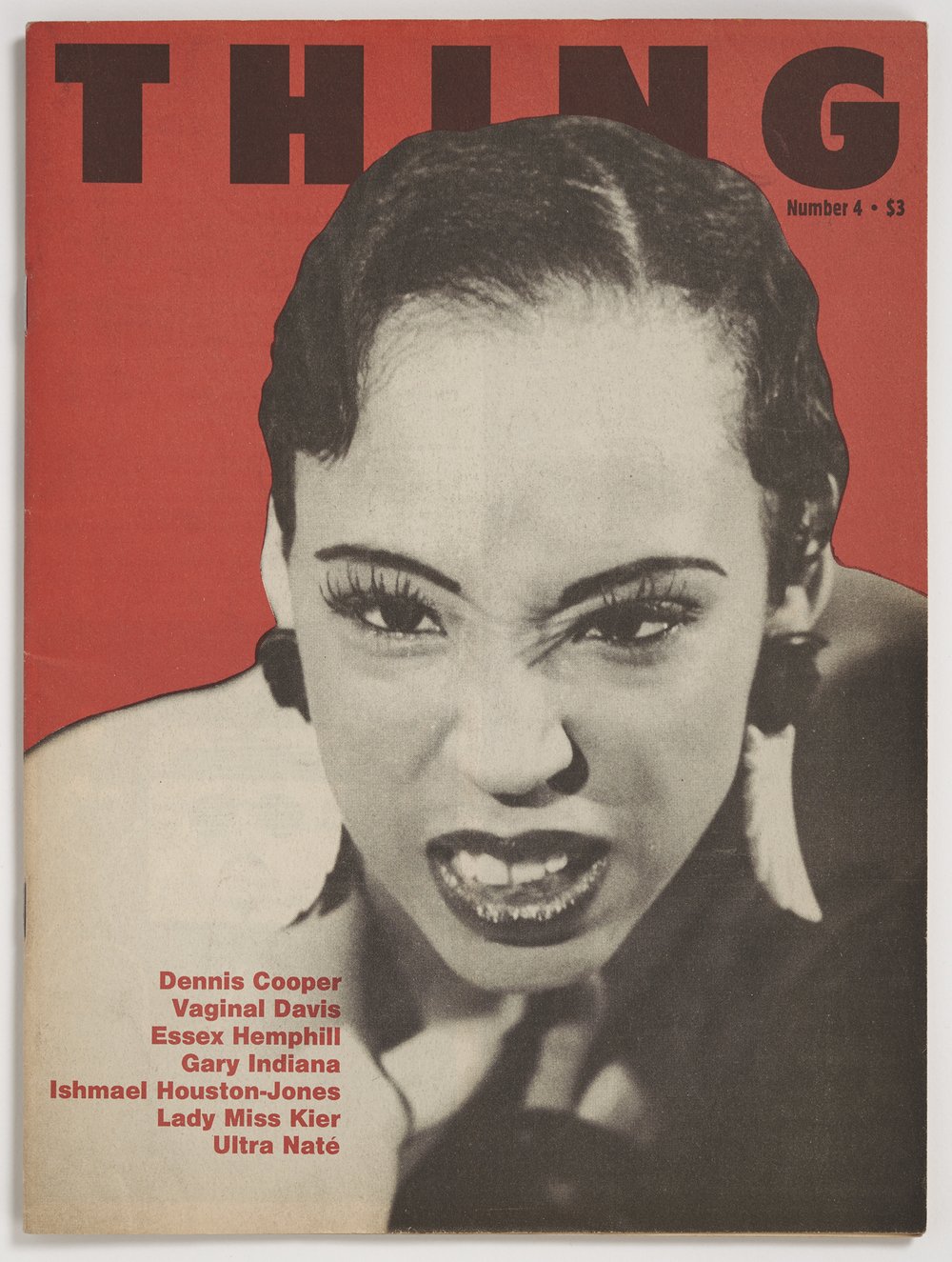

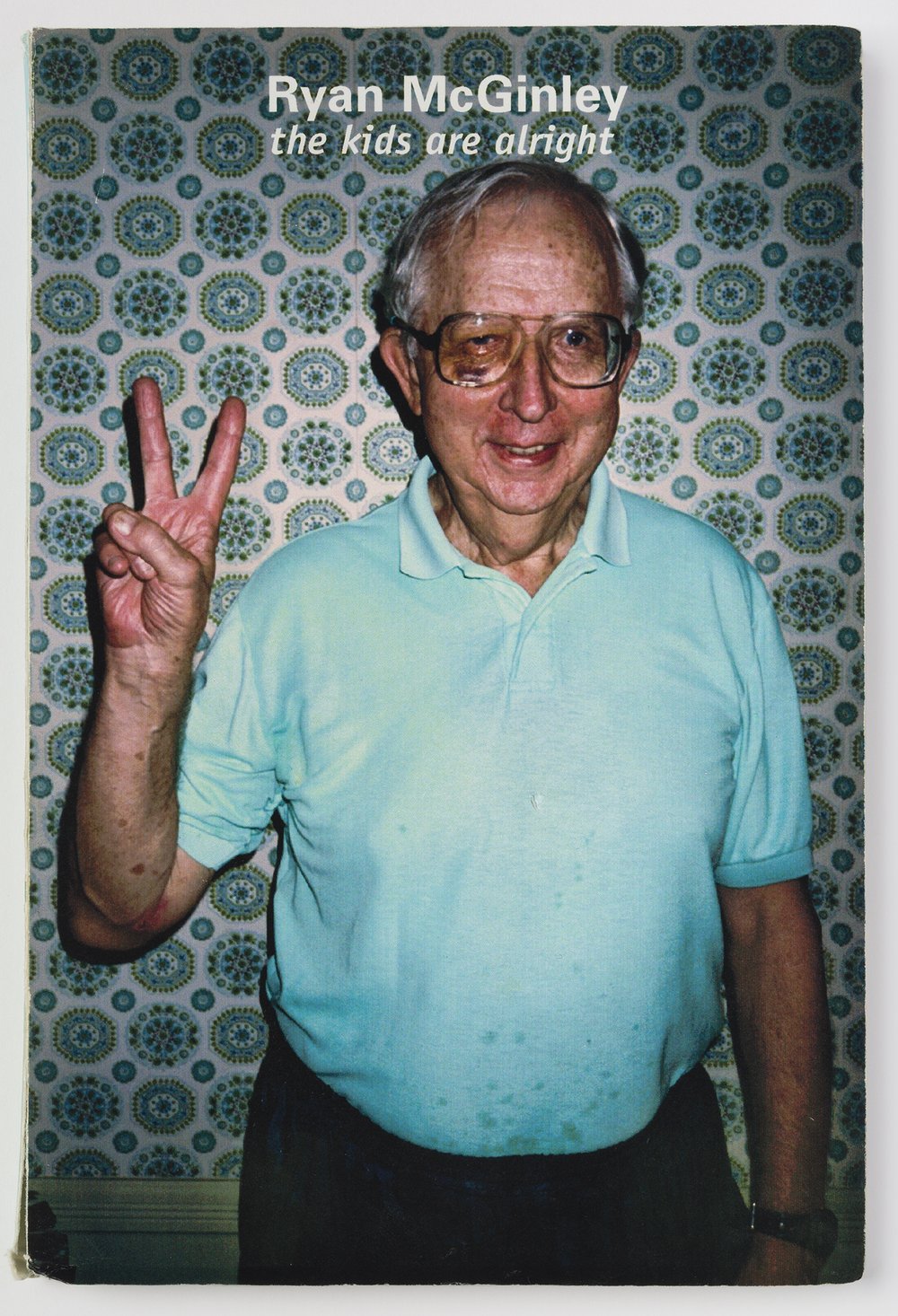

And now, the Brooklyn Museum has a new exhibit called "Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines."

It includes more than 800 images from the world of zines from the 1970s to today, organized into categories like “The Punk Explosion” and “Critical Promiscuity.”

“Zine” is short for magazine, but – as the exhibit highlights – zines are more than smaller versions of their corporate cousins. They're typically do-it-yourself endeavors, curated and crafted like small works of art.

WNYC’S Alison Stewart spoke to Branden Joseph, who is one of the exhibit's curators and a professor of modern and contemporary art at Columbia University, on a recent episode of “All Of It.”

Below is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Alison Stewart: Branden, we know what a pamphlet is or what a brochure is. What makes a zine a zine?

Branden Joseph: Historically zines have been related to magazines. We think of zines as photocopied – and the ones in the exhibit are largely like this. The classic zine might be regular 8½ by 11 paper, photocopied, folded in half and stapled.

Zines actually began in the 1930s, in mimeograph form. They were the same: cheap, quick, ephemeral and usually self-made publications, but they were related to fan culture.

They started around science fiction fandom, then moved into comic book fandom, then ultimately, in the early '70s, moved into rock fandom.

There are fan communities that are interested in certain comics or certain types of music.

Part of the ethos of these fanzines is that they're very open to reader feedback and participation. They welcome correspondence, they welcome contributions, they welcome mentioning other types of zines.

They're more open and collaborative with a community than your typical magazine, which has a gatekeeper function.

I have to ask about “manifestos.” Why is that in the title?

The title, "Copy Machine Manifestos," was actually taken from an article that was published in the San Francisco Bay Guardian in the 1990s about the explosion of queer zines in the early 1990s. That was the title of the article.

We liked it because, first of all, it foregrounds the copy machine. But also, very often, the zine comes from people that want to get their voice heard against something they perceive as anywhere from oppressive to just plain boring. They want an alternative.

Often, the zine contains manifestos in it: “This is what we're doing. This is why we're doing it.”

Just as often, the zine itself acts as a manifesto in its form and in its content. Whether it says “this is a manifesto” or not, it serves as a billboard of a particular person or a particular group's point of view.

And, of course, if you're a card-carrying art historian or frequent museum visitor, you know that manifestos are often associated with art movements.

It's a very art historical term, while it's also an activist term. We like the way that it's switched between activism and art, because that's exactly what these zines largely do.

Some of the wall text explains that the earliest zines came out of something called “mail art” networks. What was mail art?

The exhibit that Drew Sawyer and I put together is largely zines done by artists. The earliest zines in our exhibition are basically from the ‘70s and on.

There was a group in the '70s that was national and international, interested in correspondence art. They were interested in making things that were cheap and ephemeral and that could be mailed to other people.

You’d mail your piece to someone, and they would mail you another piece, or maybe they would even take the piece you mailed to them and modify it and send it on to somebody else.

The earliest artist zines that we chronicle in the exhibition came out of these types of networks.

For instance, we have what was called the “New York Correspondence School Weekly Breeder.” It was a joke on “weekly reader.”

It started as a one page mailer that was sent around. Then another person took it over. The first person was an artist. The next was Stu Horn, an artist in Philadelphia.

Stu Horn took that and made it a two-page mailer. Then it was passed on to a man named Tim Mancusi, a San Francisco artist. He made it into a full-fledged zine of 35 pages.

Some of the earliest artist zines that we chronicle come out of these communities that were using the postal system as an alternative to the high art museum as a place to show and disseminate their work.

Can you pick out any connective tissue among the zines that come out of our area or out of Brooklyn?

The exhibition actually begins with a publication, “November '69,” which was done by John Dowd and Stanley Stellar.

John Dowd lived in Park Slope. He worked at the Eagle Bar in the West Village. He was a graphic designer. He was a pop artist before that. His studio was in Brooklyn.

The exhibition begins in Brooklyn. We have an opening piece when you come in, by Yusuf Hassan, Kwamé Sorrell of BlackMass Publishing in collaboration with Ari Marcopoulos and the musician, rapper and musician, Mike, aka dj blackpower, so all of them have Brooklyn connections and roots in the front of the exhibition.

When we get to the last section, many of them are also Brooklyn-based: Candace Williams, who just moved from Los Angeles to Brooklyn, Devin Morris, who had moved a couple years before from Baltimore to Brooklyn, Neta Bomani.

There's a throughline of Brooklyn that starts and ends the exhibition, but we also have Manhattan, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Guadalajara, Mexico City, Toronto, Vancouver – which are all pretty important nodes throughout this exhibition.

How would you describe the zine landscape today, given everything we've been talking about?

Zines are incredibly popular now, especially among artists. They’re a way for artists to be able to make work that can be bought cheaply, given away, that can have a community function and network function – people can have a zine from an artist for $5, whereas maybe they can’t buy a painting.

As we worked on this exhibition from 2019 to now, we really saw a wave of production. It's as popular now as it's ever been.

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines is on now through Mar. 31 at the Brooklyn Museum.

A Spike Lee exhibit opens at the Brooklyn Museum The most popular books New Yorkers are reading now, according to 9 indie booksellers I tried it: NYC's hottest (but potentially risky) new manicure