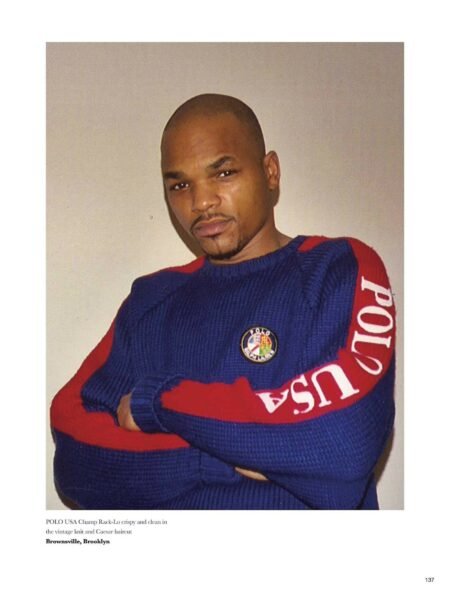

The Brooklyn crew that turned preppy fashion into a streetwear staple

Feb. 21, 2024, 5 a.m.

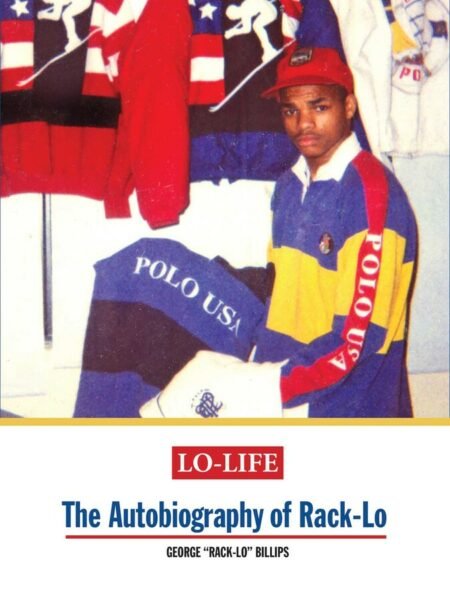

A new autobiography from the Lo-Lifes' founder details the rise of the movement.

A group of kids from Crown Heights and Brownsville, Brooklyn, created a fashion movement in the late 1980s that continues to echo into today's streetwear culture.

The crew, known as the “Lo-Lifes” for their obsession with Polo Ralph Lauren clothing, would steal massive amounts of gear off the racks of department stores and mall shelves. By collecting and wearing Polo exclusively, they became walking billboards that helped give rise to the brand’s unlikely status as a staple of urban culture.

A new autobiography from the Lo-Lifes' founder George “Rack-Lo” Billips, published by Brooklyn’s powerHouse books and distributed by Simon & Schuster, sheds light on the origins of the movement, its influence in hip-hop and streetwear, and Billips' journey from criminal to career counselor.

As brands like Rowing Blazers and Aimé Leon Dore have brought a measure of preppy style back to streetwear, Billips’ book chronicles the way Black youth in New York first embraced luxury clothing while subverting its traditional associations.

It also documents his life's journey from gun violence and run-ins with police to becoming the founder of a global fashion movement with chapters on four continents.

Billips describes the Brooklyn of his youth in the early 1980s as being much more provincial, with close-knit communities that stuck mostly to their own neighborhoods. He says that when he moved from Crown Heights to Brownsville, he was one of the first of his friends to bring the neighborhoods together.

Billips catalogs his early years by the sort of trouble he got into. He and his friends kept pigeons on their rooftops – an expensive habit for a young kid – and paid for it with side hustles like packing groceries and pumping gas, as well as breaking into payphones and stealing.

“I didn't really care about the consequences,” Billips said. “It was all about survival, getting by, and not really wanting to depend on mom and pops for too much.”

A formative experience at age 10 awakened his lifelong love of fashion.

It was Easter Sunday, which Billips says his mother took very seriously. He and his brother got their first pair of Puma sneakers, Lee jeans and fresh Caesar haircuts.

“Coming outside on the Easter Sunday and seeing all the attention I was getting, all the compliments, it definitely sparked my interest,” Billips said. “It’s something I carried on with me throughout my life.”

He and his friends started “racking up” clothes – stealing them off the rack at department stores and mall shelves. Polo Ralph Lauren quickly became one of their favorite brands. Billips says he began wearing head-to-toe Polo at age 14.

Any major department store that sold Polo, we gave them hell.

George "Rack-Lo" Billips

“Any major department store that sold Polo, we gave them hell,” Billips said.

He described a game of one-upmanship. When the brand released a new line, kids would compete to see who could be the first in the neighborhood to wear items that nobody else had.

“It was like a cult in Crown Heights and Brownsville,” Billips said. “Eventually it caught wildfire.”

Dallas Penn, another early “Lo” collector and a pioneer of the “sneaker internets,” describes the brand as transformative for both himself and Black culture, referring to Ralph Lauren as hip-hop culture's “greatest provider of cosplay.”

“Sometimes I want to look like an outdoorsman, or I want to look like someone who owns a yacht and knows the difference between a stern and a bow,” Penn said. “Ralph Lauren provides cosplay for whatever you imagine yourself to be.”

Penn said wearing luxury clothing that was advertised as the domain of upper-class white culture not only changed his self-perception, but also influenced how others perceived him.

“It made people who had not seen us previously, see us,” Penn said. “I can’t tell you how important that is to a Black youth, to be seen as somebody presentable and attractive. It empowers all of us.”

The Lo-Life movement quickly spread beyond the Brooklyn neighborhoods where it originated with the help of an essential 1990s cultural vector: the rap music video.

New York rappers like Grand Puba and Wu-Tang Clan rocked Polo in hit 1990s videos, wearing pieces that have since become coveted and expensive collectors’ items. The brand even brought back one vintage piece worn in a Wu-Tang video for a sold out run in 2018.

“Lo-Lifes were really responsible for those artists being in those pieces in the early '90s,” Penn said. “Because you would go to a nightclub then and see 50 kids wearing Polo and be like, what is this?”

He adds that many of today’s major prep-inspired streetwear brands like Noah, Rowing Blazers, and Aimé Leon Dore, owe a debt to both Ralph Lauren and the Lo-Lifes who embraced him.

“If you really undress those brands, you’ll see how derivative they are of what Ralph has done,” Penn said.

Ralph Lauren Corporation did not respond to a request for comment. But Billips and Penn both said the brand has slowly and quietly come to embrace its popularity in streetwear culture.

“A lot of the fashion you see on Fifth Avenue, it all starts from the street,” Billips said. “That’s why you see companies now really pursuing Black models. We’re big influences, so they try to capitalize on that.”

Penn said that Blackness has become a valid way to present a brand in a way that wasn’t the case 30 years ago.

“Had Ralph Lauren started using the Black face years ago, I do not know that the brand would have lasted,” Penn said.

Billips says the company has sent photographers and influencers to several of his recent events – his annual “Lo Goose on the Deuce” party brings Lo-Lifes from around the world to 42nd Street to show off and share their collections.

Billips is now in his 50s and has turned his life around. He works as a career counselor at a national nonprofit in Brooklyn and credits a similar youth program with changing his life. He now buys his Polo new and still maintains a massive collection of rare pieces, many of which are imbued with the streetwear resale value he helped create.

Families and children celebrate hip-hop at Carnegie Hall Soak up hip-hop history in Brooklyn and more things to do around NYC in the coming week First-Ever And "Long Overdue" Hip Hop Museum Groundbreaking Draws Luminaries To The Bronx