Meet One Of NYC's Most Famous Murderers: 'The Last Pirate Of New York'

June 7, 2019, 11:05 a.m.

Did you know... there was a study where they say there are 450 pirates living in Manhattan in the 1859.

Rich Cohen, author of the New York Times best-selling books Tough Jews, Monsters, and Sweet & Low, and contributing editor at Vanity Fair and Rolling Stone, has written a new book, The Last Pirate of New York. The book covers the life and crimes of Albert Hicks, one of the city's most infamous murderers. We recently spoke with Cohen about the new book and the case on which it was based.

Let's start at the beginning with the gangsters—what drew you to this topic? It seems like it's been a theme in your career. Well, I think it's two things: one is I grew up in a suburb of Chicago and everything was so perfect and everybody was so well behaved that I sort of craved a little more toughness and a little variety, like a missing essential vitamin. And then second of all my father was from Bensonhurst Brooklyn, where a bunch of the guys from Murder Inc. lived later in their lives. And he used to tell me stories about them in lieu of regular bedtime stories, and I became fascinated by these stories and his childhood. So when I came to New York after college I just started looking for the places he told stories about. And that led to Tough Jews, and Tough Jews led to The Last Pirate.

There's this enormous gap in history between Tough Jews, which takes place in the mid-century and this story of Albert Hicks, which takes place almost 100 years before in the middle of the 19th century. So what drew you to that? Well, it was the origin of the underworld. I sort of felt like if you could understand what New York was like the summer before the Civil War, you can understand how it became the city that we all know.

An interesting part of the book is that this entire world that you're describing was swept away—erased entirely by the war and by the development of the city that came afterward. How did you track down this lost city? Amazingly, for something that happened in what might as well have been biblical times as far as New York is concerned, there is a surprising amount of information because it was this big story. Albert Hicks went on this killing spree in New York Harbor and then ran and there was a manhunt and a big trial which was really well covered, there were like 50 daily newspapers in New York at the time... It was on the front page of papers for months and months and months and then he gave a confession where he told the whole seemingly fantastical story about his own life and crimes. Plus, [there were] court transcripts and police records. So if you put all that together for something that happened so long ago you'd get a pretty good picture. There are things you don't know, like what happened to his wife and what happened to his child—they didn't cover that because they didn't care.

An interesting part of the book is that this entire world that you're describing was swept away—erased entirely by the war and by the development of the city that came afterward. How did you track down this lost city? Amazingly, for something that happened in what might as well have been biblical times as far as New York is concerned, there is a surprising amount of information because it was this big story. Albert Hicks went on this killing spree in New York Harbor and then ran and there was a manhunt and a big trial which was really well covered, there were like 50 daily newspapers in New York at the time... It was on the front page of papers for months and months and months and then he gave a confession where he told the whole seemingly fantastical story about his own life and crimes. Plus, [there were] court transcripts and police records. So if you put all that together for something that happened so long ago you'd get a pretty good picture. There are things you don't know, like what happened to his wife and what happened to his child—they didn't cover that because they didn't care.

How long did it take you to track down all this stuff? Well ever since I was working on Tough Jews I became completely fascinated by Albert Hicks and I made various earlier attempts to try to write the story. So I've been gathering stuff on him since 1999. But when I seriously threw myself into it, it took about a year.

When was the first time you heard of Albert Hicks? When I did research for Tough Jews, some of the old gangster experts and historians knew about Hicks as a kind of early example—in Gangs of New York, the Herbert Asbury book, there's a little section on him and he covers him as kind of like a Paul Bunyan-like early figure in the underworld. There were famous early gangsters like Monk Eastman and Arnold Rothstein and even Bill the Butcher... So it's before all of them, and what I found fascinating about him was all these other guys were in gangs. Hicks was so tough he didn't have to be in a gang. People were in a gang for protection, he didn't need protection. People needed protection from him.

That's what's so interesting to me about Hicks—because he’s not really a gangster, he's a solo operator, a sort of strange combination of a pathological serial killer and a highwayman of an earlier age, because he works alone generally or with one partner, where when I think of a gangster, I think of people working together in a large group committing crimes. Early on it was large groups like these huge ethnic tribes, like the Forty Thieves and The Dead Rabbits. And then in the modern era, they become underworld businesses like the mob that's in The Godfather with guys like Arnold Rothstein and Meyer Lansky. What this guy did was create the popular culture idea of the gangster as the guy in flashy clothes, the guy who's sort of terrifying, the guy who you want to get next to you to hear what he's going to say, and the guy covered by the press. So he almost became an antihero in New York and became so famous that the wax figure of him was on display in P.T. Barnum’s museum, until the museum itself burned down.

So he wasn't a gangster in the sense of Don Corleone, but he was something like John Gotti sitting in front of the Ravenite Social Club, in very fancy clothes for everybody to see and for kids in the neighborhood to emulate. And he even was hung [on Liberty Island, back when it was still known as Bedloe’s Island, in front of 12,000 spectators] in a specially made electric blue suit with anchors stitched in the sleeve. He was very particular about his clothes and the way he looked. He was fancy.

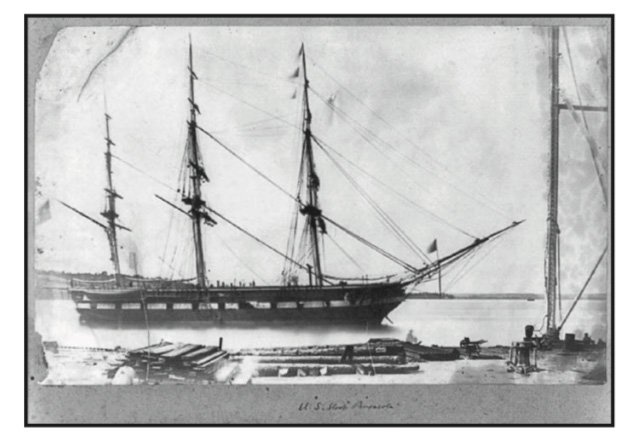

What part of the story really grabbed you the most? To me it's the way it opens—New York was a town that was really dedicated to its waterfront and sailors. That's where the business came from. It was a huge port. And one day people wake up and there is this ghost ship—a ship with no crew just drifting around New York Harbor which was a terrifying sight for sailors and the Shore Patrol, which was a New York Police waterfront brigade, goes out to investigate and the ship is completely empty but they find blood everywhere they look, and they bring the ship in to South Street Seaport. They anchor it next to Fulton Fish Market and a group of detectives come aboard and they examine the ship, and they find four severed fingers and a thumb. And that's the beginning.

What part of the story really grabbed you the most? To me it's the way it opens—New York was a town that was really dedicated to its waterfront and sailors. That's where the business came from. It was a huge port. And one day people wake up and there is this ghost ship—a ship with no crew just drifting around New York Harbor which was a terrifying sight for sailors and the Shore Patrol, which was a New York Police waterfront brigade, goes out to investigate and the ship is completely empty but they find blood everywhere they look, and they bring the ship in to South Street Seaport. They anchor it next to Fulton Fish Market and a group of detectives come aboard and they examine the ship, and they find four severed fingers and a thumb. And that's the beginning.

Ultimately they find this guy who's using a fake name and then it leads them on this incredible manhunt. So the whole thing from his crime spree to the manhunt to being brought back to New York with huge crowds watching the train, to the trial, to his execution, is three months between March and July of 1860, the summer before the Civil War. And to me, it’s the entire city in microcosm.

It’s sort of an incredible, cinematic story. Right, because he goes everywhere and he's on the waterfront, and the waterfront is like a real-life Pirates Of The Caribbean. There was a study where they say there were 450 pirates living in Manhattan in 1859. And something like 90 people that year alone had been shanghaied, which means they'd been basically drugged in a bar, and dragged aboard a ship and told to work or swim—and in the worst case scenario you'd end up on a ship bound for China, which is where the term shanghaied came from.

That's an interesting part of the story because when you're investigating Hicks's life, a lot of the stories told it as a tale where he had been shanghaied earlier in his life and as revenge he becomes a killer. Albert Hicks did become kind of a pop star and a model for people, especially in the slums. So over time, his story got changed to where he was this kind of hunter who went on the ship and killed these people, but he was a guy who had been shanghaied and killed these people because they kidnapped him, which is something you could have some sympathy for. And that's how the story was reported in Herbert Asbury’s book and everything that followed. When you go back and read what really happened, to the newspaper coverage and to the police testimony, that's not at all what happened. What happened is he went looking for a ship where he felt the crew was small enough, and that would be carrying cash, so he could kill the crew and take the cash and get away. And it's a crime he committed many times before. This time he just got caught.

What's incredible to me is how many witnesses there were essentially from the moment he pulls up on the shore of Staten Island to the moment he is caught. It's almost like there are dozens of people who saw him. Well looking back from our point of view it's completely wild the way he acts spending his money, and making a spectacle of himself like a pirate... but at the time it was very early in the life of police detection. There were no fingerprints, there was nothing. Unless you were seen or caught at the scene of the crime, if you got away and into a crowd, they never had a chance of catching you, and 50 percent of the murders in New York didn’t even come to trial because they could never find the people who did it.

Hicks made all these mistakes and had bad luck. And the prosecutors said it was God who was watching him, and God brought him back—the one eye he could not escape from. And he wants you to do your duty as New Yorkers to clean up the city. That’s direct from the transcript of the trial which is unbelievable—it's such a perfect courtroom statement.

Speaking of the trial, talk to us about Isaiah Rynders, the Federal Marshal. Isaiah Rynders is a fascinating figure because that's like Tammany Hall. He'd been a captain on riverboat ships up the river. And he then went out West. He was involved in knife fights. He was a shark on riverboat gambling and he ended up coming back to New York and owning all these little groggeries in the slums. He controlled a huge army of young kids who were a gang—the Dead Rabbits—when they fought, they carried a dead rabbit on a pole in front of them. Teddy Roosevelt was trying to stamp him out, but he was able to get out the vote. So politicians go to him and he brings out people to vote and vote and vote and vote. Those are the repeaters who vote again and again. And because of his service, James Buchanan made him the Federal Marshal, and as Federal Marshal, you had all kinds of ways to make money. He was in charge of Albert Hicks, which was a huge story and one of the ways he enriched himself was by selling tickets to his hanging.

I first came across Rynders reading about the Astor Place Riots in 1849, where there was a riot between natives and British-supporters, over whether an American or British actor was the best at playing Macbeth. Rynders was actually there organizing the rioters. He almost seems like a more prototypical gangster—he has his illegal businesses, he is all caught up in the political machine, he's got a number of different grafts going. Yes, Rynders used Hicks as a star to enrich himself and then became kind of weirdly close to him and was standing next to him when he died.

I love how the book turns in the middle from the account of his crime and punishment, to this narration where you hear him talking to Rynders, the jailkeepers, and the press, and narrating his really crazy life story. Yes. Well he gave this confession and you take it with a grain of salt, but the fact is he confessed to a lot of crimes committed all over the world, and his confession is used to solve all these unsolved crimes. So a lot of the details were corroborated.

He essentially admits to killing 100 people. He couldn't remember the number. He'd been on whaling ships, so he'd been to the Sandwich Islands, which are now Hawaii. He’d been to Tahiti. And then he'd been all over Mexico and the parts of Mexico that became California. And he'd been there in the gold rush and the really wild detail is that he had gotten a huge amount of money and he went down to Mexico and opened a bowling alley.

What struck me is how cosmopolitan he was—he travels all over the known world, from the Pacific to South America. He gets to Liverpool. He comes back. He's only 40 years old, and he essentially spent 20 years murdering on a reign of terror. Yes, he got on this sort of three-way route where he would go from New Orleans to Liverpool, because Liverpool was where all the cotton would go from the South before the Civil War, and then from Liverpool to Brazil and then Brazil back to New Orleans, just robbing people all along.

Right, and cutting throats, and throwing people overboard. How much of his confession do you think was actually true? You don't really know because, first of all it was a spoken confession, that was then written down by a federal marshal, and then given to a writer, and they wrote it up in the language at the time and they were trying to sell it as a book. So there was a degree of translation that happens between what he said and what they wrote. We can never know... did they add to it? He's selling a story and he was a storyteller, so to what extent did he embellish himself? We can never know that. So to me, either way, it's him telling his story which is interesting. And like I said there were various crimes he talked about that were then solved, because they never knew who did it. And not just in the United States but in South America and all over the world.

I enjoyed how the press is involved with the story, through the character of an early New York Times reporter. The New York Times was 10 years old and was trying to establish itself in a very crowded market with dozens of newspapers. And the way that you could establish yourself in the city at that time was crime stories. I mean it's still true I guess but it was really true then, and this was the biggest crime story of that year. And the reporter from the Times solves the manhunt—he was the one who figured out where Hicks was, because the reporter was from Rhode Island, and he knew all these back ways you could get to Providence without taking the main ferry.

What I love about the story is you really see New York creating itself, the ways the criminals, the law, and the press all interact. This story would repeat itself dozens, hundreds of times. Later on, you think of Giuliani prosecuting the gangsters. It's basically the same players and the same storyline of a colorful gangster brought to justice. Right, but as the police became better and better at their jobs it would become harder and harder for a guy like Hicks, who would have to become smarter and smarter, which is what happened. It's like the beginning of what would become modern New York.

An exclusive excerpt of The Last Pirate, entitled "The Ghost Ship":