Lessons In Blackness From Beyoncé's 'Homecoming'

April 19, 2019, 5:29 p.m.

Never have I seen a more perfect and generous stretch of black legacy than in 'Homecoming.' And I wish it had been available for my white parents to sit me down in front of when I was a child.

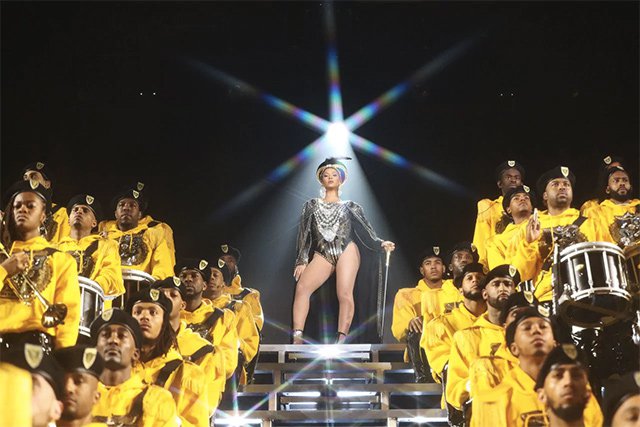

Beyoncé performing at Coachella in 2018

There are a million glorious moments in Homecoming, the new Netflix film which documents Beyoncé’s performance as the first black woman to headline Coachella in 2018, but from a black interracial adoptee’s perspective, the first, most palpable message for me was right at the start: “When I decided to do Coachella, instead of pulling out my flower crown, it was more important that I brought our culture to Coachella.”

Flower crowns are cute, and my white hippie mother made lots of them for me that I wore perched atop my scrappy, unkempt afro, but more than a flower crown, I needed culture. Black culture. My culture.

Take note, white adoptive parents, I beg of you.

While all the beautiful, brilliant black folks in my social media community stan and stay shook over Beyoncé’s new film, I would like to offer a suggestion to all white adoptive parents raising black kids, and that is to please use this film as a starter kit for how to raise a black child. I don’t even consider myself an official member of the Beyhive, which I realize is a fairly dangerous thing to admit, and obviously, her talent and star power are undeniable, but listen, I watched this film and wept for my little black girl self who careened back and forth from white space to white space in desperate search of not just representation, but of guidance on how best to embody and love my blackness. Never have I seen a more perfect and generous stretch of black legacy than in Homecoming. And I wish it had been available for my white parents to sit me down in front of when I was a child.

In Homecoming, it’s nearly impossible to miss the theme throughout of how important it is for black folks to love ourselves and our people, and to be of ourselves and our people. The sheer number of dancers, musicians, singers and performers that Beyoncé gathered and gifted with this opportunity to shine is a visual translation of what Fannie Lou Hamer once said: “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

Listen to, respect and honor your elders and ancestors. Sprinkled throughout the film are quotes from black women such as Dr. Maya Angelou and Audre Lorde, which serve as markers of memory. It is a way of lifting up the black women who came before her, who charged a path and bore the brunt, and keeping them in her spirit. Work hard, hard, hard and be humble. At one point in the documentary, Beyoncé says that the reason performers don’t want to rehearse is because it makes you humble. Whew. Say that, Ms. Knowles.

Give your child at least the option of an experience at an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) experience. I didn’t even know they existed when I was growing up in rural New Hampshire. By the time it came around to applying to colleges, all my rich, white preppy friends were applying to Dartmouth and Harvard and Bowdoin. One friend dared me to apply to Dartmouth: “You’re probably not smart enough, but I bet you’ll get in because you’re black.” I didn’t take him up on it, and ended up at the whitest state university in the country before transferring to a smaller private college. But that’s another story for another time. Beyoncé mourns the fact that she herself didn’t have a proper college experience, and the way she pays tribute to HBCUs is so rigorously intentional, with such appreciation and longing.

Surround your children with examples of nuanced black talent, not just the famous ones, and not just posters to hang in their bedroom — actual living, breathing, sweating and pulsing black bodies that exact their talent in all different shapes and hues. Beyoncé's children Blue Ivy, Sir and Rumi will never, not once, feel anything but black. Either strumming a guitar during her mom’s rehearsal with musicians, singing an acapella version of the black national anthem (“Lift Every Voice and Sing”) or whipping her braids while she hits the choreo, Blue Ivy is not just confident, she is black confident, because she is living and learning among kinfolk.

Let your child go full, entire-ass days without seeing white people. It’s OK. Above all, know that your black child wants to be black. The less exposure to blackness they have, the more strident the message that you don’t think they should want to be black. I mean, the fact that the documentary is called Homecoming — whatever meaning that carries in the traditional sense, for a black adoptee who only saw images of whiteness growing up, it means this is how and where your blackness will thrive, and will always be welcomed home.

Rebecca Carroll is a cultural critic and Editor of Special Projects at WNYC, where she develops, produces and hosts a broad array of multi-platform content, including podcasts, live events and on-air broadcasts. Rebecca is also the author of several interview-based books about race and blackness in America, including the award-winning Sugar in the Raw, and her personal essays, cultural commentary and opinion pieces have been published widely. Her memoir, Surviving the White Gaze, is due out from Simon & Schuster in 2020.