How Stonewall Transformed The LGBT Civil Rights Movement

June 24, 2019, 1:19 p.m.

How this filthy dive bar gained such a cultural halo is one of the great triumph-of-the-underdog stories in American life.

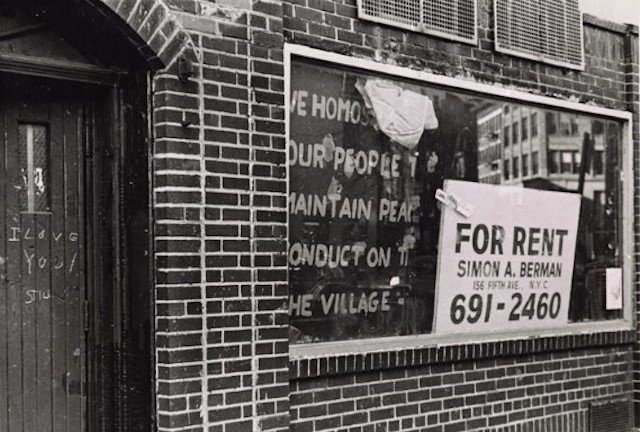

Outside Stonewall Inn in 1969.

Today when we talk about The Stonewall Inn, and what happened there 50 years ago, it’s in the ringing tones of history. How this filthy dive bar gained such a cultural halo is one of the great triumph-of-the-underdog stories in American life.

Consider Stonewall’s current credentials: President Barack Obama mentioned it in his second inaugural address, alongside Seneca Falls and Selma. It’s now the place in New York where LGBTQ people gather after a great tragedy, like the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, or a great victory, like the 2015 Supreme Court Decision that lifted nationwide bans on gay marriage. Obama declared it the first national monument to LGBT rights in 2016 and today, the tiny triangle of a park across the street has its own park ranger.

Now let’s talk about 1969.

The Stonewall Inn was just a bar then— a trashy one at that —with grimy toilets and no fire exits. It was so dirty that it had been suspected to be the source of a hepatitis outbreak the year before. One clue was that the staff “washed” drinking glasses by dipping them into a tub behind the bar.

Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt a 17-year-old runaway at the time, remembered the drill on approaching the front door. "The guy would slide a little thing open and decide whether he was going to let you in," he said. “His name was Johnny Shades.”

Listen to Jennifer Vanasco discuss this piece on WNYC:

So why was The Stonewall popular? Because it was at the center of the gay neighborhood in the West Village, and because unlike other bars, it let everyone in. There were straight-appearing men in the front room, and drag queens, transgender women and more effeminate men in the back. White people mixed with Puerto Ricans and African Americans. Plus — it had a dance floor with two good jukeboxes. In 1969, this was a very big deal.

"You felt like a human being for the first time in your life because everyone else could dance slow in their high school and every place else," said Lanigan-Schmidt.

As with all gay bars, the police raided it pretty regularly. The Mafioso owners watered down their alcohol, which was illegal, and many of the patrons weren’t wearing the required three items of clothing that conformed with their birth genders.

"There was never actually a specific rule that required three articles of clothing," said Columbia University historian George Chauncey. “But both the police and the people they were regulating thought there was such a rule and they enforced such a rule.”

To figure it out, said Stonewall veteran Victoria Cruz, the police would do “sex checks. Yeah, they would check if you were a boy or a girl.”

Here's what being gay was like in 1969: There was no rainbow flag or Pride Parade. Gay men and lesbians could be fired from their jobs at any time. They could be kicked out of their apartments by their landlords, have their children taken from them by the courts. In the eyes of the world, they were perverts and pedophiles and mentally ill. This scare film about the dangers of “homosexuals” was shown to school children at the time.

But early in the morning of Saturday, June 28th, 1969, something was different. It was a hot night; there were a lot of locals hanging around outside. Usually, police raided bars fairly early on a weeknight, before there were a lot of patrons and before they became drunk. But Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, who lead the morals unit (now it would be called vice), had been ordered to shut the place down this time, not just raid it. Stonewall book author David Carter suspects it’s because of a blackmail scheme based there, but others say it was just because raiding gay bars was something the police did as a matter of routine.

Pine led a team of about a dozen officers into the bar. The lights slammed on, and the NYPD started checking IDs, making arrests and sending people out to the police van. But once outside, bar patrons resisted.

"I think it was like a lark for them," Pine said in a 2004 interview. "It was a release of energy. They could now fight back for all the times they had to slink away without being able to say anything and take whatever crap the cops were giving at them. And once it broke loose it was very contagious."

Street kids started appearing on the scene, joined by people in the neighborhood who heard something was going on. Someone pulled a parking meter out of the sidewalk and used it as a battering ram against the front door that was normally the domain of Johnny Shades. Others pried up paving stones from the street. A car was overturned.

Martin Boyce, 21 at the time, says he will never forget what it was like to be there. “A riot is not a pretty thing and it's not a stationary thing,” he recalled. “You don't stay in one place for very long, you move, you twirl.”

That’s what happened. The crowd grew and pushed at the bar. Pine realized his officers were overwhelmed and ordered them into the bar, where they barricaded themselves inside with a Village Voice reporter. Later, he would say it was scarier than his experience in World War II. Pine went to each of his officers, looked into their eyes, and told them not to shoot. He later said he was worried that a single shot would trigger a hundred others.

Soon, dozens of riot police arrived from the Sixth Precinct with their shields and helmets. They pushed the crowd back, only to see it circle around the block and come at them from the other side. Boyce says that at one point, he and other men joined in a kickline and started singing, "We are the village girls. We wear our hair in curls. We wear our dungarees above our nellie knees."

The exact chronology of events that night—who did what and how—remains disputed. Some say transgender people of color started the uprising; some say white gay men; some say runaways. Some say it was a butch lesbian resisting arrest who agitated the crowd into acting. But whoever was there at the beginning matters less than what the movement became.

The riots went on for three days, and another day the next week. After that, some gay New Yorkers started thinking of themselves differently. After standing shoulder to shoulder, members of the LGBTQ community felt like they were now in this together. George Chauncey says, that’s why Stonewall is remembered to this day. "I think for most people, it does boil down to just the idea that gay people can resist," he said. "That still means something. That's still powerful."

Soon after that night, members of the community formed the Gay Liberation Front, which then seeded more activist organizations around the country. And then, a year after Stonewall, thousands of LGBTQ people marched up Sixth Avenue to Central Park for a "Gay-In" to honor the uprising—it was the inaugural Pride march, though it wasn’t called that. But it was the first time a large number of people came together to say publicly: Here we are, gathered in the daylight, instead of a dark bar. And we’re not ashamed to be who we are.