Gracie Mansion Is Amazing. So Why Have Mayors Turned It Down From The Start?

May 5, 2021, 5:01 a.m.

The answer is optics and, once, a marital implosion.

AVAILABLE: 18th century mansion nestled within 11-acre park in exclusive Upper East Side neighborhood of Yorkville. Five bedrooms. River views. Staff included. Rent: $0. Must be winner of most recent campaign for mayor.

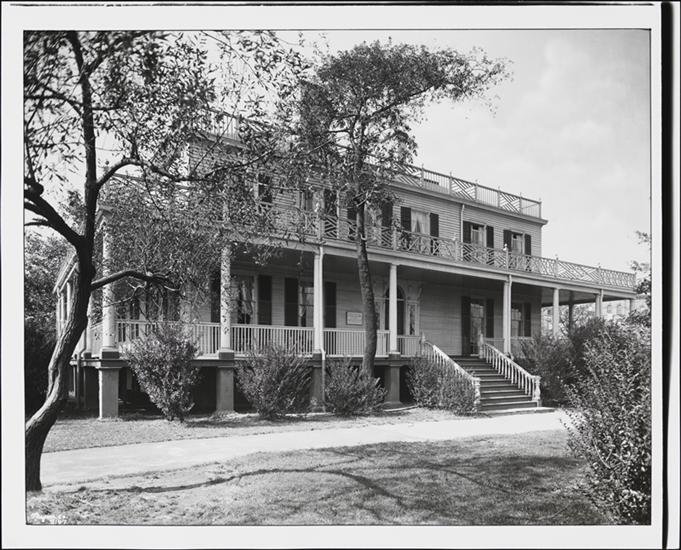

It’s one of the sweetest deals in all of New York: an official residence that was dubbed the city’s “little White House” by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. He thought the description would appeal to Fiorella LaGuardia, the “rubbery little crusader” of large ambition who’d come out on top in the 1934 mayoral election. So the Power Broker took control of the former country home of prosperous Scottish-born merchant Archibald Gracie, intending to use it to raise the stature of the office. He fixed it up with heating and electricity and a fresh coat of exterior paint. Rugs were laid and draperies hung. Then Moses proudly offered it to the stumpy son of immigrants who had just become New York City’s leading man.

LaGuardia turned it down.

Over the nearly nine decades since, several mayors have followed suit. Some preferred to stay put in their own digs. Others merely delayed before succumbing to the move. And one was essentially evicted -- hounded from the grounds in the midst of the kind of spectacle that would come to be his specialty: the unspooling of a sordid public scandal.

Of course that mayor is Rudy Giuliani.

But why would any politician slug their way through a primary followed by an election and then bypass such a juicy perk: living gratis in one of Manhattan’s few remaining historical mansions? The answer, in a word, is politics.

LaGuardia swept into office as the antithesis of his predecessor, the dashing Jimmy Walker, whose second term had been cut short by bribery charges. (He escaped from them via European exile in the arms of a Ziegfeld girl.) The Great Depression, then at rock bottom, sent voters in search of a leader who’d work tirelessly to alleviate their privation, which is what LaGuardia had wholeheartedly promised to do. Now imagine him taking a ride with Robert Moses to a remote corner of Manhattan to be shown a fancy building that might function as his private seat of opulent sequestration.

Of course he said no.

Paul Gunther, executive director of the Gracie Mansion Conservancy, said politics will always play a role in a mayor’s decision about whether to move into the city’s official residence. “Gracie is very emphatically a symbol,” Gunther said. “It's a palace, if you will.”

Gunther said LaGuardia chose to stick with his humble apartment on East 109th Street, where he’d lived for a decade while serving in Congress. “He thought it was indulgent to go into a mansion. He was like, ‘I'm very happy where I am, embedded in the fabric of the city.’"

Until he changed his mind. Gunther says it took eight years of wheedling by Commissioner Moses and the threat of Nazi air raids, to make it happen. “Finally in 1942, Mayor LaGuardia and his wife and two children moved in for the last term of his administration. He had resisted, but World War II forced his hand. It was safer and easier to escape, were that necessary, from a blitzkrieg.”

LaGuardia left office in 1945, after which five mayors moved in and out of Gracie Mansion, largely uneventfully. Then in 1978, came Ed Koch.

Azra Dawood, a postdoctoral curatorial fellow at the Museum of the City of New York, says the newly elected Koch faced a classic New York real estate problem. “He was living in a rent-controlled apartment near NYU and was at first hesitant to move into Gracie Mansion,” she said. “I imagine that, like all New Yorkers, once he found a good deal he had hoped to hold on to it.”

Koch also weighed the move politically. Throughout the campaign, he’d invited reporters into his cramped Village apartment and burnished his regular-guy-cred by showing off its narrow galley kitchen. Dawood recalls that, “Koch famously said, ‘It's small and I like it. I know where everything is in it.’"

But Koch eventually gave in and settled uptown. And like any regular guy who finds himself living in a mansion, he got used to it. He even established the Gracie Mansion Conservancy in 1981, a public-private partnership that restored the house and manages it still.

In 1994, Rudy Giuliani took office and moved in straightaway. Six years later, he invited his girlfriend to join him. That's when Donna Hanover, his wife of 16 years and still in residence at the mansion, raised her hand to object. The MCNY’s Dawood said Hanover had the advantage in the struggle that ensued. “At the time that Rudy Giuliani was separating from his wife Donna, she was actually president of the Conservancy.”

That's right: Donna Hanover was in charge of the group that runs the mansion.

She found out about the end of her marriage after Rudy announced it at a press conference in May 2000. Three hours later, Hanover spoke to a gaggle of reporters at Gracie’s entrance on 89th Street and East End Avenue. She told them that only one half of the city's first couple would be remaining on the premises. She then turned on her heel and walked back inside, making it clear that it would be her.

The mayor ended up crashing at the Midtown apartment of his friend Howard Koeppel, who later claimed that Giuliani reneged on his promise to preside at his wedding after gay marriage became legal in New York. Giuliani, classy as ever, threatened to show up for events at the mansion with girlfriend Judith Nathan on his arm, never mind that his wife and children were still living there. Donna Hanover won a restraining order to keep them away. (Footnote: Giuliani got revenge of sorts by marrying Nathan at Gracie long after the end of his mayoralty. But it was not enough to insure the couple’s bliss: they divorced a few years later.)

The drama was great for the tabloids but bad for the mansion’s upkeep. “You can speculate then that this is why the mansion falls into disrepair,” Dawood said. The New York Times described it this way in 2001:

The paint is peeling, balcony railings are rotting and the lawn is worn down to a bare spot. Gracie Mansion, the 200-year-old official residence of the mayor of New York, has grown, in a word, shabby. "The house is crying," said former Mayor Edward I. Koch, a one-time Gracie Mansion occupant and a regular critic of the current mayor, Rudolph W. Giuliani. ''The house wants to be loved.''

Enter billionaire Michael Bloomberg, who won office later that year. He took one look at Gracie and declared he’d continue to live in his double-wide, Upper East Side townhouse with its accents of Egyptian marble, thanks for asking. It’s a decision he stuck to over three terms. Bloomberg did spend part of his fortune repairing the mansion and, as Architectural Digest gushed, adding historically atmospheric features like “sprigged wallpaper in a late-19th-century palette of buttercream and faded rose.” (The result was a far cry from the rat-friendly confines described by Giuliani, back when he’d stood on the porch and glimpsed unsavory instances of scurrying in the shadows -- make of that metaphorically what you will.)

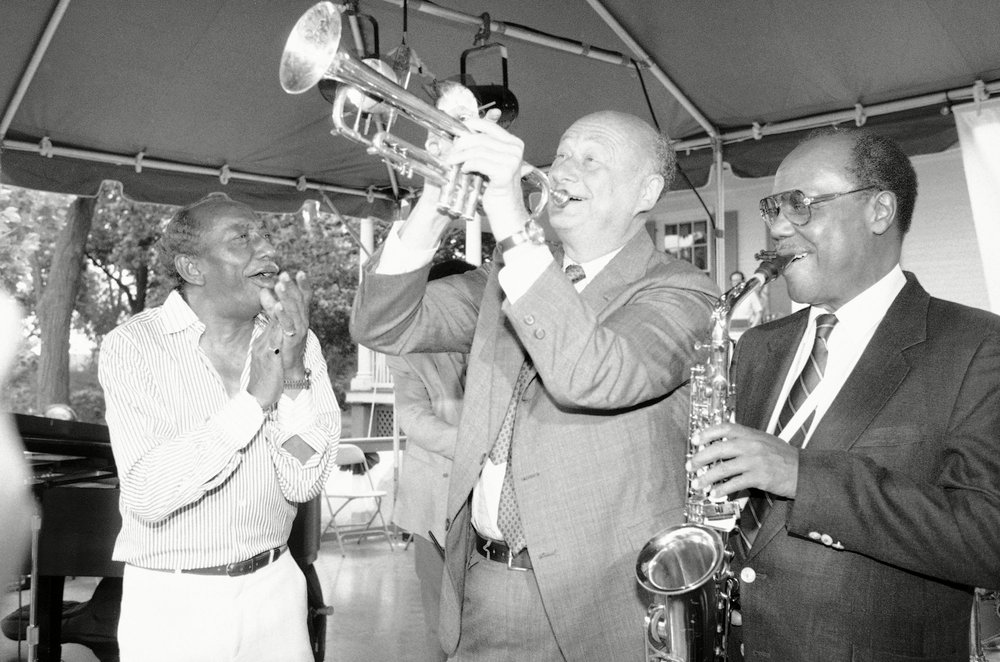

During the Bloomberg administration, the mansion became the elegant setting for municipal events, private functions, and meetings with foreign dignitaries. It was also opened for regularly scheduled public tours, a practice that continued until the Conservancy had to suspend them at the start of the pandemic.

In 2014, the story came full circle. Like LaGuardia before him, Bill de Blasio had campaigned as the voice of marginalized New York, which meant the mansion presented him with a similar image problem. De Blasio wanted to stay put in his beloved and relatively humble Park Slope home. But the family took a vote and he lost. That meant part of Gracie Mansion needed to be turned into a residence once again. The New York Post reported that a raft of fragile antiques in the rooms upstairs were moved to storage and replaced with donated West Elm furniture.

“And then Mayor de Blasio and his first lady moved in,” Conservancy Director Gunther said, adding that the mansion’s decorative elements have been left largely undisturbed. “They have respected that continuum, but changed the art and refreshed the narrative at the same time.” Gunther was referring in part to Catalyst, an in-house exhibition overseen by First Lady Chirlane McCray that “explores the connections between art, protest, and social change.”

At the end of this year, the de Blasios will decamp from the Upper East Side and return to Brooklyn. Then the politically-loaded question of whether to mansion or not-to-mansion will fall to his successor.

The yellow-ochre wooden structure on a bluff above the East River provides a city address in a sylvan location that’s three-quarters of a mile from the nearest subway; it remains quaint, sublime, and politically problematic. But, presumably, fewer rats now call it home than when Rudy Giuliani lived there.