With bomba and La Fonda, El Barrio remembers photographer Hiram Maristany

May 17, 2022, 5:06 p.m.

Hundreds gathered at El Museo del Barrio this weekend to celebrate Maristany, a Black Puerto Rican artist and activist who died in March at age 76.

Hiram Maristany never really drank... he preferred café with milk and two sugars. But mourners leaving the former Young Lord documentarian’s grand memorial at El Museo del Barrio on Sunday wanted to linger at La Fonda, his favorite neighborhood restaurant, for a toast.

More than 300 people attended the service at the institution Maristany had helped to found and at one point directed, nearly 50 years ago. A procession performing bomba, an ancient music and dance tradition rooted in Puerto Rican slave tradition, led mourners out of the auditorium after they'd heard from family, curators and former Young Lords about the Black Puerto Rican artist’s life and work.

Maristany's photos featured the struggle and joy of living in East Harlem in the 1960s: images of neighbors at a clothing drive, light piercing through a shirt being held up admiringly, or a pig being roasted in an alleyway for a party, surrounded by damaged cars.

“Youth – because he loved them – would ask, what was my mother like? What was my grandmother like? What was my great-grandmother like?" former Young Lords chairman Felipe Luciano told the audience. "He took those pictures so that you could see who we were."

Maristany’s soft spot for snapping neighborhood kids playing in fire hydrants or drawing chalk portraits of themselves with wings, Luciano suggested, may have developed because his own childhood was cut short.

“He had to become a man very quickly," he said. "It does something to you when you're not allowed to jump up and scream, to play in the streets.”

Maristany, born in 1945, lost his father at a young age. But he found guidance from a social worker, who gave him his first camera at the age of thirteen.

A 1963 documentary episode from NBC-TV’s “Show of the Week,” titled "Manhattan Battleground," captured Maristany as a young kid living on 111th Street after he realizes someone had just stolen his camera. In black-and-white footage shown at the memorial, a lanky Maristany wiped tears from his eyes while he searched aimlessly around stoops for his prized possession.

“My father experienced betrayal at a very young age, so it was hard for him to let people in on a personal level,” said Maristany’s son, Pablo Maristany, who at times was estranged from his father.

But he didn’t let that betrayal tear him away from his responsibility to his community. In his 20s, Maristany was already considered the grumpy old man of the Young Lords Party, known to make younger members do push-ups if they were late for events. Luciano said they needed his stability, his tough love... oh, and his car.

“He was already a man," Luciano recalled. "He was married – had a Volkswagen. In fact, it was Hiram Maristany who brought some of the Lords to Chicago so that we could form a chapter. Can you imagine if we didn’t have that car?”

Inspired by the Black Panther Party, Maristany also helped create a free breakfast program for neighborhood schoolchildren, while documenting the most effective and confrontational efforts of the Young Lords: when they commandeered an x-ray truck to test residents in East Harlem for tuberculosis, or occupied the People’s Church.

His consistent presence and activism in the neighborhood made people remember his impact for decades.

Irma Colón, among the mourners who headed to Maristany’s favorite restaurant after the memorial, was born and raised in El Barrio. Sitting at the bar of La Fonda, Maristany’s unofficial office, she held up her phone to show a photo Maristany took of El Museo del Barrio when it was just a storefront. He had helped to found the institution, which is now one of the leading venues for Latine art in New York City.

“In 1975, I remember going here as a kid!" she said. "They also had a mobile unit that would come to schools and teach us about art."

Colón and Maristany became reacquainted years later at La Fonda, where they both were regulars, and remained friends for over 20 years. But Maristany’s impact on her life had already been cemented. “Art became my thing," Colón said. "I got an art degree. I became an art teacher.”

Like his activism, Maristany’s art was meant to spark alleyways of possibilities for people living in El Barrio.

“If you look at his work, hope has been the underlying message," Alita Maristany, the artist's daughter, declared onstage at the memorial.

"He found hope in the everyday lives of people living in East Harlem," she said. "He found hope in the Young Lords Party – free health clinics, free breakfast programs. He found hope in the Taíno ruins in Puerto Rico. He found hope in El Museo. He found hope in Hunter College. My dad always found a little bit of hope."

Maristany’s hope also presented itself in the mentorship he gave younger artists, like the Puerto Rican-born visual artist Miguel Luciano and the Cuban filmmaker Amílcar Ortiz.

“He was so wonderful at intergenerational dialogue,” said Yarimar Bonilla, the director of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College. “He believed in young people... even though he thought he had a lot to teach them, but he believed in everything they had to say.

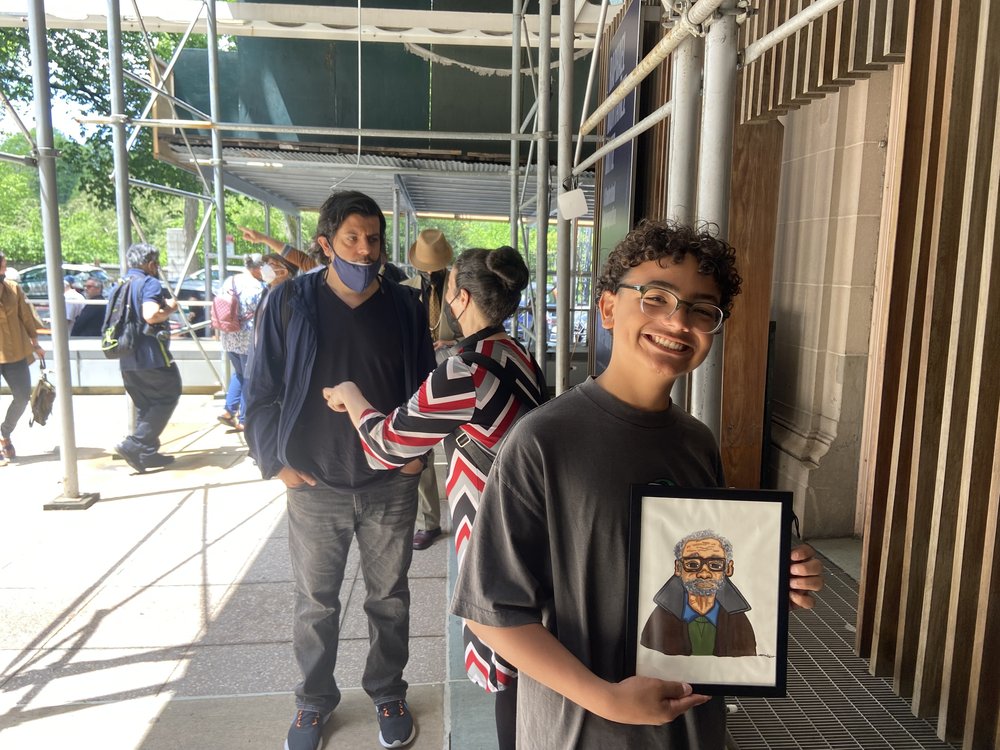

That mentorship has carried on in the wake of his death.

Yiselie Cabrera was in the lobby after the memorial with headphones around her neck and a necklace of the Puerto Rican flag. Cabera learned about Maristany’s work while sitting at La Fonda, where his photos are hung above the seats like a public museum. The 18-year-old didn’t know a lot about the photographer, but wanted to honor his life before returning home to Cleveland for the summer to live with her parents, both of whom are from Puerto Rico.

“I’m filled with so much love afterwards y con poder,” Cabrera said. She’s studying philosophy and African-American studies at Fordham University, and has just started to branch out from a campus she feels is very white, in order to find community.

“I’m an artist as well, and I felt very disconnected from me and my art and activism,” she said. Her parents had just come to the city to help her pack up all her things. "But I really want my sketchbook now.”